Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowLibby Klesmith hates her student loan debt. In fact, she said, “It sucks.”

As a practicing South Bend attorney who loves her job, Klesmith is happy where she’s at in her career. But the debt she acquired from higher education has been limiting.

Six years paid with 14 more to go, the 31-year-old associate at Tuesley Hall Konopa LLP said if she weren’t doing income-based repayment, her student loan payments would consume 80% of her monthly salary.

“I’m not from here, and there is the incentive, ‘Should I move to some place like my bigger hometown where I could get a job that makes more money to pay them off?’ I don’t want to, and I’m not planning to, but that’s always kind of in the back of my head,” she said.

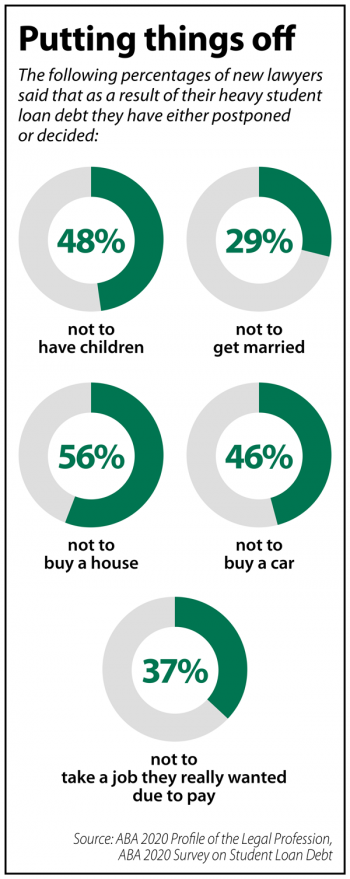

Klesmith isn’t the only young attorney lamenting her student loan baggage. A recent American Bar Association survey of nearly 1,100 young lawyers found that many new attorneys are making major financial, personal and career sacrifices as a result of their student loans. That includes decisions ranging from marriage and children to making big purchases or taking vacations.

Making sacrifices

For Klesmith, the biggest sacrifice she’s had to make because of her student loan debt is her living arrangements.

“I could live on my own, but I have a roommate because it’s easier and it really helps cut down on expenses,” she said. “I don’t own a house, but my student loans are roughly equivalent to the cost of a nice house for a mid-upper-class family in South Bend.”

“I could live on my own, but I have a roommate because it’s easier and it really helps cut down on expenses,” she said. “I don’t own a house, but my student loans are roughly equivalent to the cost of a nice house for a mid-upper-class family in South Bend.”

The same is true for Jasper County Prosecutor Jacob Taulman, who said he definitely feels the impact of his student loan debt.

Attending at out-of-state law school with no financial aid created a considerable amount of debt upon Taulman’s graduation. Even with an annual salary of more than $150,000, the elected prosecutor said he still can’t pay the interest on his student loan monthly payments.

“If I can’t pay that at a decent salary, a person who is fresh out of law school that has a public defender salary that’s only making $40,000 a year — that’s absurd,” Taulman said.

Student loan debt has also put up roadblocks for certain opportunities in Taulman’s personal life.

“As a gay man, marriage was not something that was legal when I graduated,” he said. “It’s more challenging of course to have children. So that would include pretty expensive routes, and those are essentially almost out of the question completely because I am putting all of this money toward my student loan debt as opposed to other things.”

On the flip side, Fort Wayne attorney Sarah Beiswanger said her decisions to get married, buy a house, buy two cars and have a baby quickly might not have been well-advised in hindsight.

“My husband and I both just happened to need cars and we needed a house and all of this other stuff. So basically we had to do all of that, and it really created a financial crunch,” Beiswanger said. “So I think instead of postponing those big decisions, it has postponed smaller decisions. Like, do we really need another pair of shoes? Do we really need to take a vacation?”

Where’s the debt?

Among the ABA survey’s respondents, the median cumulative debt at law school graduation was $160,000, including law school, undergraduate programs and other educational expenses.

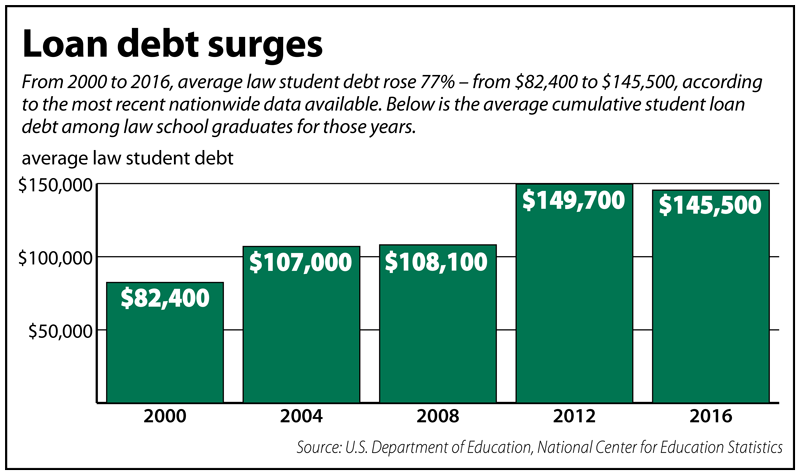

In comparison, the average law school graduate had $145,500 in cumulative student loan debt in 2016, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics. That’s almost 77% more than in 2000, when the average law student debt was $82,400.

But two Hoosier law school deans have seen more positive trends than negative in recent years.

Dean Karen Bravo of Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law said that beginning with the Class of 2016, fewer IU McKinney students have been borrowing money to get through school. Among those who do borrow, they are borrowing less on average.

“I think that is owing in large part to philanthropic gifts that we received from our donors, and those donor scholarships help to defray the cost of law school,” Bravo said.

The Indianapolis law school has seen a declining trend of student borrowing all the way through the Class of 2019, Bravo said. The figure has dropped from 86% for the Class of 2016 to 78% for last year’s graduating class. That decline can be attributed to endowed scholarships as well as law school scholarships, she said.

The Indianapolis law school has seen a declining trend of student borrowing all the way through the Class of 2019, Bravo said. The figure has dropped from 86% for the Class of 2016 to 78% for last year’s graduating class. That decline can be attributed to endowed scholarships as well as law school scholarships, she said.

Similarly, dean Austen Parrish of the IU Maurer School of Law in Bloomington said he has seen debt decrease significantly in the last five years for his graduating students.

“We generally have between 25% and 35% of our class that graduate with no federal loan debt at all,” Parrish said. “… Our average debt load for those who have graduated with loan debt is usually under $95,000. And if you look at the entire class, our average debt last year of students graduating was approximately $65,000, which includes three years of living costs.”

Switching careers

Beiswanger started off her legal career working in a private law firm, which she said partially shielded her from the reality of financial constraints posed by student loans.

“I was making pretty good money. And then I transitioned to working for the government after two years. I think in combination with making less money, I became more acutely aware of how much I was spending on student loans,” she said.

Noah Gambill also made a career switch, leaving private practice where he worked alongside his father to take a position with the Indiana Department of Child Services. His choice to make the change was primarily based on his family’s need to take advantage of the public loan forgiveness program.

“We were going over our family budget in January, looking at how much we were paying on our student loans and where we were going to be in the next 10 to 20 years,” Gambill said. “It’s kept my wife up at night because there is so much uncertainty.”

But now that he’s working for a state agency, Gambill said he has seen improvement in both his finances and mental health. He hopes to make gains on his student loans to pave a better way forward for his children’s education.

“There is a sense of security — and hopefully that maintains, as well as a steady belief that my student loans will be forgiven,” Gambill said. “We continue to make payments on them with the hope that there is a light at the end of the tunnel.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.