Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhen Southern Indiana District Senior Judge Sarah Evans Barker used to compare her courtroom to its companion, she noted something was amiss. While one courtroom was adorned with elaborate murals from decades past, the other was not.

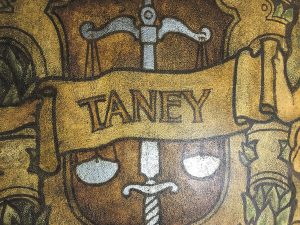

“I often wondered why,” Barker said. That was, until workmen touching up chipping plaster in her courtroom in the late 1990s accidentally uncovered a swatch of color under the surface. A year-long art restoration process was launched, revealing that Barker’s courtroom did, in fact, have paintings of its own — an earthy-colored frieze containing crests listing the names of more than a dozen former United States justices.

Among them, however, was a name whose presence troubled Barker: Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, arguably best known for authoring the notorious 1857 majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sanford. In that case, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded African-Americans, free or enslaved, could not become citizens. The decision also declared the Missouri Compromise of 1820 — legislation that restricted slavery in certain territories, unconstitutional.

“It was up there plain and clear,” Barker recalled upon first noticing the name. “I remember thinking, ‘Well what a bad choice. Why would somebody choose that?’”

But concerns about Taney’s name hovering in the back corner of the room didn’t come to a head until a young man visiting Barker’s courtroom raised his hand with a question.

“He was sitting at the end of the jury box closest to where the mural was,” Barker remembered. “He said, ‘Why, in a place that honors the values of justice and equality, would you pay tribute to and honor that person?’ And I remember thinking, ‘Well now, finally, someone has asked the right question, because that is a hard question.’”

Making a change

After ruminating on the man’s question, Barker brought the issue of removing Taney’s name from the mural to her fellow judges, who unanimously agreed a change needed to be made.

After ruminating on the man’s question, Barker brought the issue of removing Taney’s name from the mural to her fellow judges, who unanimously agreed a change needed to be made.

A proposal to remove Taney’s name in keeping with the broader national trend to remove controversial historical symbols from public spaces was presented to the Court Historical Society, which also nearly unanimously agreed to pursue an alteration of the mural. Permission was further granted by the General Services Administration, which advised that, pursuant to the National Historic Preservation Act, a group of community members would need to first gather to offer input on any mural alterations.

Eighteen community members consisting of art historians, attorneys, judges and other art professionals convened for a roundtable discussion in August 2018, said court historian Doria Lynch. A lively, hours-long discussion ended with a consensus that something should be done. But no one could agree what that was.

“Going in and even coming out, there was no unanimity on what we were going to do, and whether we should do anything,” Lynch said.

Ultimately, three potential ideas stemmed from the roundtable: leave the space blank as a teaching vehicle, remove all 13 names and replace them with words like “equality,” “fairness” and “justice,” or replace “Taney” with “Marshall,” representing longest-serving Chief Justice John Marshall and Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall, the court’s first African-American justice. The group settled on the third option.

Thus, with the appropriate approval, the district court took the final steps to remove “Taney” from the mural and put “Marshall” in its place, officially completing the project in July 2019.

“It’s much better now,” Barker said. “We did the right thing.”

The decision to pursue the alteration project, however, was not wholly unanimous. Concerns were raised about the potential offensiveness of making changes to artwork in a historically significant building, Barker said. But members of the roundtable did not fail to consider and discuss the societal tensions concerning the removal of controversial artwork from the public eye and preserving historic artwork, Lynch said.

“I would call it civil, but passionate,” Lynch said of the discussion. “It’s a sensitive subject on all different accounts, whether that’s race and equality or some version of censorship or — I hate to even use the term — whitewashing the past.”

The deciding factor for Lynch was when District Judge Tanya Walton Pratt brought a copy of the Dred Scott decision to the roundtable discussion, fully marked up.

“What echoes in my mind was her expressing how hurtful the opinion was,” Lynch said. “From there, there was no turning back.”

Visual culture, community values

Herron School of Art & Design associate professor Laura Holzman said the decision to remove Taney’s name from the mural was important for the court and the community. She pointed out that a statue of Taney’s likeness had been removed from the Maryland Statehouse in 2017 amid mounting community pressure.

“I think that it’s possible that somebody might balk at the removal of his name, but we have to recognize that communities have the right to decide that pre-existing art no longer reflects their values,” Holzman said.

“I also think it’s a really important statement for the court to make that they are choosing to no longer honor someone associated with such a really painful part of the country’s past,” Holzman added. “It’s easy for people to forget how powerful images can be for not only those who make them, but also those who view them.”

Richard Garnett, a Notre Dame Law School professor with First Amendment expertise, said he has mixed feelings about the decision to remove Taney’s name from the mural. On the one hand, Garnett noted it would be very difficult, in terms of consistency, to eliminate all public references and acknowledgements of people in the past who held controversial views.

“And if we are not going to eliminate all of them, how do we decide which ones we are going to select for elimination?” Garnett asked. “Are we going to apply a standard to historical actors that, if applied evenly, really would require the erasing of realistically almost all historical figures?

“On the other, it seems to me that it’s perfectly appropriate for governments to decide to celebrate some things and not others,” Garnett continued. “Just because someone was memorialized in the past doesn’t mean we have to memorialize them today.”

Acknowledging the societal tensions, Barker said it remains important to note when decisions were made and out of what cultural context to honor people whose careers modern-day society looks back on and finds unworthy.

“It’s not that we are changing the history, it’s that we don’t need to honor the people who did not act honorably,” Barker said. “That is a part of our history, and it’s a sad fact. But the imperative is that you look at it with your eyes wide open and accept it for what it was, and if it doesn’t need to continue to be that way, then you have an obligation to change it.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.