Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now Nearly one in five Hoosiers is on Medicaid, a program that pays for medical care, hospitalization, drugs, skilled nursing and other services for low-income and disabled people.

Nearly one in five Hoosiers is on Medicaid, a program that pays for medical care, hospitalization, drugs, skilled nursing and other services for low-income and disabled people.

But the future of the program is now up in the air after the Trump administration announced in January it would allow states to add eligibility requirements, benefit changes and drug-coverage limits.

The administration has framed the changes as an opportunity for states to better control Medicaid spending, in part by giving them the option of switching to a block-grant funding approach, one with per-person payments that cap spending.

The moves could end Medicaid’s days as an open-ended entitlement in favor of limits to what the government is willing to spend on health care for certain enrollees.

Hanging in the balance is health care coverage for millions of needy Americans, who have counted on it since the program launched more than 50 years ago.

The changes also could affect doctors, hospitals, nursing homes and other health care providers who stand to lose revenue if states spend less on Medicaid programs.

The Trump administration’s plan is just a few weeks old, and many experts say they are still trying to understand its potential impact. But they say Indiana could be vulnerable, as the state consistently ranks low in per-capita income and in general health.

“We live in a state that is ranked 41st of 50 states for health status,” said Paul Halverson, dean of Indiana University Fairbanks School of Public Health. “That means we are generally more sick with great risk factors for disease.”

He added: “Compared to the current Medicaid plans that provide coverage for people who have a lower income coupled with poor health and limited options, I fear the block-grant programs could put our most vulnerable people at increased risk.”

Much depends on whether Indiana decides to seek a waiver from the traditional Medicaid program in favor of a block grant.

Gov. Eric Holcomb’s office declined to comment to IBJ. The Indiana Family & Social Services Administration, which oversees Medicaid programs, declined to make officials available for an interview. The Indiana Republican Party also declined to comment. State Rep. Cindy Kirchhofer, chairwoman of the House Public Health Committee and of the Marion County Republican Party, did not return calls to IBJ.

John Zody, chairman of the Indiana Democratic Party, said opting into block grants is a bad idea. FSSA announced Feb. 14 it has no plans to seek a Medicaid block grant at this time.

“Gov. Holcomb owes Hoosiers an answer on whether he intends to take up the Trump administration’s offer to end Medicaid as we know it,” he said.

Sharing the cost

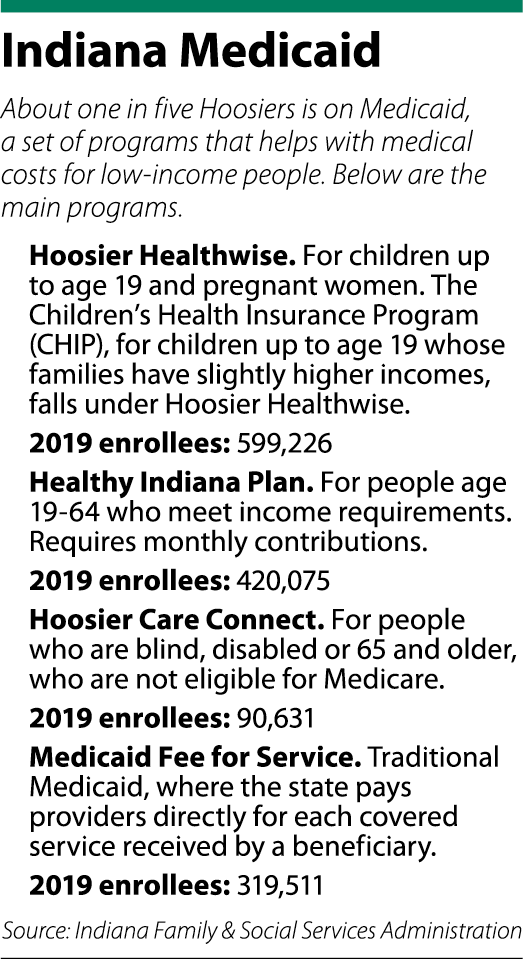

Under the current Medicaid program, people who are low-income or disabled are entitled to coverage. In Indiana, 1.4 million people — or 18% of the population — is covered by Medicaid, including the Children’s Health Insurance Program, better known as CHIP.

Across the country, Medicaid programs pay for nearly half of all births in the United States and for 62% of seniors living in nursing homes. It also pays for hundreds of thousands of people with physical and intellectual disabilities, reimbursing them for inpatient care and home-based services including personal care, such as bathing and feeding.

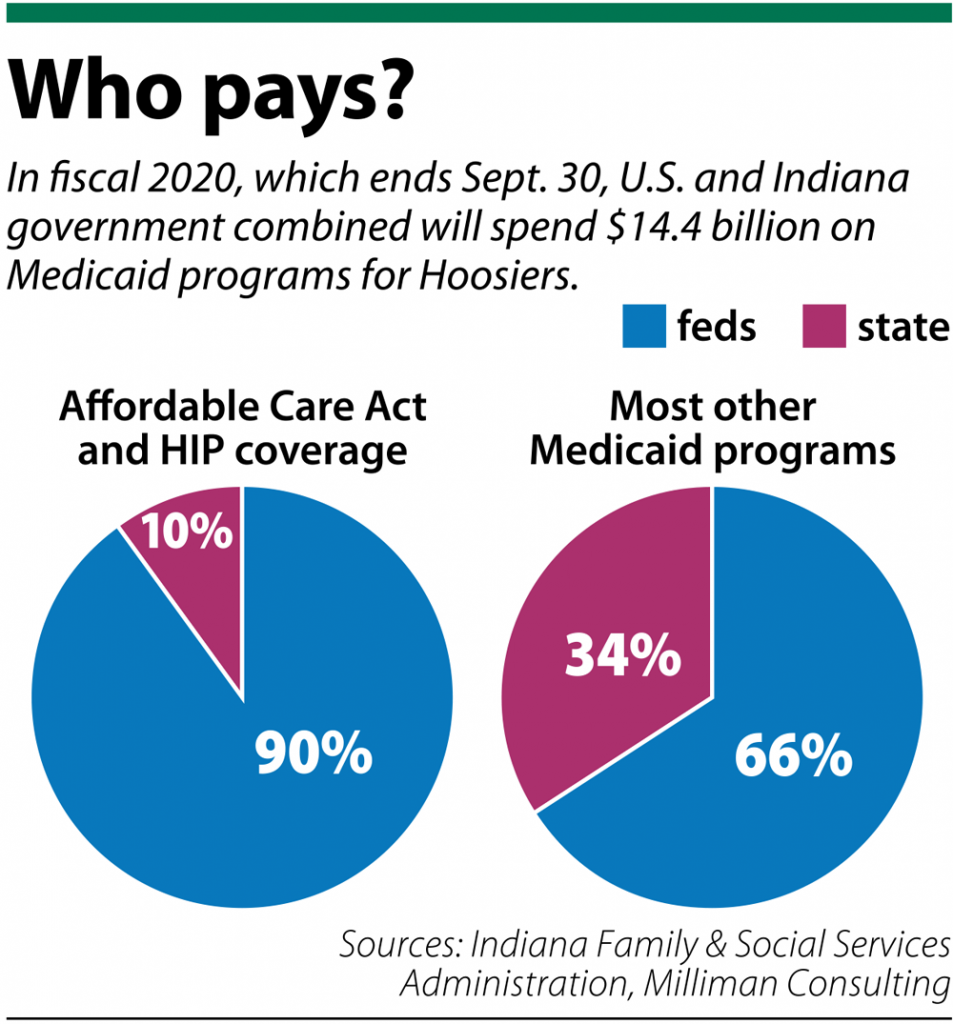

The federal government always has provided the bulk of the support for Medicaid, with unlimited matching payments to states based on whatever they spend. In Indiana, most Medicaid programs are paid through a funding split, with the federal government paying 66% and the state 34%.

The one exception is for adults who gained health insurance coverage in recent years under the Healthy Indiana Plan, whose enrollment swelled from about 35,000 to more than 400,000 after President Obama’s Affordable Care Act became law. For that, the feds pay 90% and the state pays 10%.

The one exception is for adults who gained health insurance coverage in recent years under the Healthy Indiana Plan, whose enrollment swelled from about 35,000 to more than 400,000 after President Obama’s Affordable Care Act became law. For that, the feds pay 90% and the state pays 10%.

Altogether, the price tag for the state’s Medicaid programs last year was $14 billion, of which the state paid $2.5 billion. Spending on Medicaid programs nationally has soared from less than $1 billion in 1966 to nearly $600 billion last year. It now accounts for about 10% of the federal budget.

The escalating costs have alarmed some policymakers, especially conservatives, who say it is unsustainable. Those favoring the block-grant approach the Trump administration is offering states say it would reduce the federal deficit. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates block grants could cut federal Medicaid spending by as much as one-third over the next decade.

Coverage details

The Trump administration is calling the new Medicaid pathway “Healthy Adult Opportunity.”

The block-grant changes wouldn’t affect children, pregnant women, elderly adults or people with disabilities, the Trump administration said. They would apply to adults under 65 without disabilities in expanded Medicaid programs and adults not covered by traditional Medicaid programs who aren’t disabled or receiving long-term care.

It’s unclear how much money Indiana would receive under the block grants compared with traditional Medicaid. The figures have not yet been published, and the formulas are so complex that health care experts are still trying to figure them out.

“I have not seen the proposed details of the plan,” Halverson of IU’s Fairbanks School said. “Generally, creating a block grant program can create greater flexibility for states in designing plans to best fit their context. [But] the unfortunate reality is that … block grants can invariably lead to arbitrary limits on eligibility and coverage.”

Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, announced the program Jan. 30, saying it gives states more flexibility to design innovative programs that best fit their needs.

“It’s a bit of a D.C.-centric idea that only D.C. will do the right thing,” she said during the rollout.

Before she went to Washington to work for the Trump administration, Verma worked in Indiana on health care policy for governors Mitch Daniels and Mike Pence. She helped redesign the state’s Medicaid program and is credited as the architect of Daniels’ Healthy Indiana Plan.

When the Obama administration offered states the option to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, Verma and Pence got federal permission to create a different kind of model.

They used funding from the Affordable Care Act to build out the Healthy Indiana Plan and required participants to put some “skin in the game” by contributing from $1 to $27 a month.

The federal waiver that permits the Healthy Indiana Plan expires at the end of this year. State officials say they hope to get a renewal but declined to comment further on how the state might approach an overhaul in Medicaid funding.

“We are pleased that CMS is providing other states the flexibility to innovate the way Indiana has innovated with the Healthy Indiana Plan,” the Indiana FSSA said in a statement. “We are committed to focusing on administering Medicaid and the Healthy Indiana Plan. In fact, we just submitted our request to renew HIP for the next 10 years.”

Range of reactions

Verma’s latest Medicaid reform plans worry Democrats and many patient advocates, who say tightening eligibility requirements and reducing benefits would hurt beneficiaries. Some say a lawsuit is inevitable.

“It is clear that these Medicaid block-grant proposals are just a disguise for a plan to cut people off from the health care they need to survive,” said Fran Quigley, clinical professor at the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law and director of its Health and Human Rights Clinic.

If the price of medicine goes up, or more Hoosiers need care because the economy worsens, funds might not be available, he warned.

The Indiana Hospital Association said Indiana’s history of expanding Medicaid has been successful in covering more people, but a move to block grants could hurt that progress.

“We believe Indiana has already been very successful in negotiating innovative, state-based Medicaid reforms without putting limits on future federal funding,” said Brian Tabor, the group’s president.

The Indiana State Medical Association said it has not taken a position on Medicaid funding but is studying the issue.

Holcomb has shown signs he is comfortable with tightening Medicaid rules. Two years ago, his administration rolled out the Gateway to Work program, under which many Medicaid recipients would be required to work, go to school, volunteer or participate in other qualifying activities for 20 hours a week.

But last year, Indiana suspended the requirement after two groups sued the state in federal court, arguing the requirement could illegally jettison thousands of Hoosiers from medical coverage.

One of the groups that brought the suit was Indiana Legal Services. That group is now studying Trump’s Medicaid changes. “We are definitely keeping an eye on the issue,” said Adam Mueller, an attorney and the group’s director of advocacy. “If it appears to be something that Indiana does decide to look into, we will be looking at it and exploring any legal options we think might be appropriate.”•

— IL senior reporter Marilyn Odendahl contributed to this report.

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.