Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAs a young lawyer in 1970 just starting his practice, Douglas Church countered his uncle’s job offer by asking for more money.

He was inspired by his uncle, Manson Church, to become an attorney, and he attended Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law at his uncle’s suggestion. While he was a student, the younger Church spent his days studying and doing legal research for the attorneys at his uncle’s firm that is now Church Church Hittle & Antrim.

By the time he fielded the offer from his uncle, Church already had three other firms wanting him to join their offices, so maybe he was feeling a little bold. The young lawyer proposed his salary be increased by $1,000 a year.

Manson Church said no. Douglas Church still accepted the job, and Hamilton County benefited the most from the transaction.

In a career that has spanned 50 years, Church not only developed his own private practice but also played an integral role in the blossoming of Hamilton County. He served as attorney for the town of Fishers from 1980 through 2015 and for the city of Noblesville from 1988 through 1996, helping those communities formulate and implement strategies for growth.

Church led the group of volunteers that transformed the county swimming pool into the Forest Park Aquatic Center in Noblesville. Also, he was a key part of the effort that saved Fishers’ Conner Prairie and turned it into the premier outdoor living history museum that it is today.

Characteristically, Church deflects the praise for his contributions to his community.

“There’s always people willing to step up and get engaged,” he said. “It’s been a gratifying thing to watch over the last 50 years the folks who came together to create a community as highly regarded as Hamilton County is.”

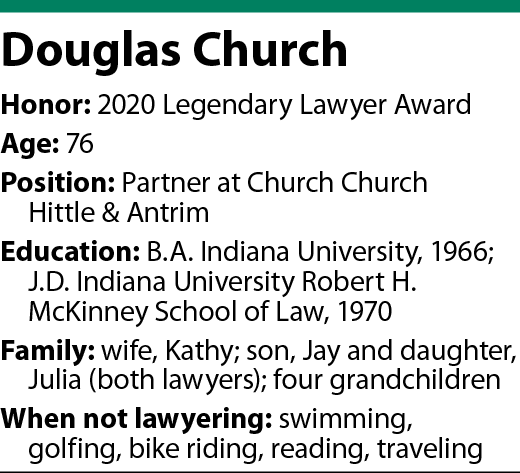

His colleagues in the legal profession are not so hesitant in acclaiming Church’s accomplishments and his friendship. For his dedication to legal ethics, community involvement and public service, his peers in the Indiana Bar Foundation recognized him with the 2020 Legendary Lawyer Award.

“There is not another person who possesses greater insight, greater passion or greater humility than Doug,” Indiana Supreme Court Justice Steven David said in a statement. “He is everything that comes to mind when one thinks of what a legendary lawyer is and what a legendary lawyer means to our profession.”

Second-shift work

Church’s unsuccessful attempt at securing a higher starting salary was not his first disappointment in the law. Preparing to graduate from Indiana University in Bloomington, he made a pact with four of his friends that they would all go to Harvard Law School. Five applications were sent but only four acceptance letters came back.

Not knowing what to do, Church followed his uncle’s advice and met with the dean at IU McKinney. He enrolled in the Indianapolis law school, where he found “great faculty” and classmates who were committed to earning a J.D. and practicing law. Church described his law school years as a “fabulous experience.”

His foray into municipal law began shortly after he started practicing when his uncle took him along to a planning commission meeting. Church enjoyed municipal work, getting into such details as figuring out how big the sewer pipe needed to be to serve the development that would soon sit on what was then an open field.

His legal guidance to Fishers and Noblesville was his “second-shift work,” since often the various boards and councils would convene in the evenings after he had spent a full day serving clients at his firm. Still, he saw municipal law as the “art of what’s possible,” and he especially liked being in same room as people coalesced around an idea or objective.

“All in all, pretty good decisions were made because there were good people in position to make those decisions,” Church said. “It was fun to be part of that.”

Church was a natural choice for city attorney when Mary Sue Rowland became mayor of Noblesville in 1988. The pair had a long friendship serving together in the local chamber of commerce and participating in community activities, and he had even encouraged her to run for the office.

At the virtual reception Oct. 15 honoring Church on receiving the Legendary Lawyer Award, Rowland remembered him as always prepared. He readily had the answers that helped the elected officials and residents make good decisions for their community.

“It is you, Doug, that has made Noblesville, Fishers and Carmel what (they are) today,” Rowland said. “Not you alone, but you have a way of gathering people to join you no matter what the project.”

Bettering his community

Bettering his community

One example of Church’s ability to lead was his coordination of the all-volunteer effort to save the county swimming pool and turn it into what is now the Forest Park Aquatic Center. The facility had fallen into disrepair by the mid-1990s, so Church and others formed the Friends of Central Pool, which took over the lease and made a number of improvements such as the installation of an Olympic-size swimming pool, diving towers and the Fast Freddie waterslide.

Church said he helped save the pool for the` “very selfish” reason that he wanted a place to swim. A former member of the IU water polo team and a current member of U.S. Masters Swimming, he was first introduced to water as a 4-year-old overcoming polio. He instantly loved being in the pool because there he could be as active as the other kids.

Describing himself as a “fickle person” who needs to be engaged, Church said his volunteer work in the community gave him the chance to stretch and have interests outside of the practice of law. He does not have the patience to serve on what he called “tea and crumpets” boards, but that is where he found himself when he joined the board of directors at Conner Prairie.

Berkley Duck, retired partner of Ice Miller LLP, was also on the board. At the virtual reception for Church, Duck recounted the years-long turmoil that erupted when the members began questioning Earlham College’s stewardship of the museum and of the endowment created by Eli Lilly.

Church was appointed as chair of the board’s governance committee in 2000. Duck recalled Church’s work to understand the terms of Lilly’s gift and to reform Earlham’s management policies. In June 2003, the negotiations culminated with an ultimatum for Conner Prairie to accede to Earlham’s views.

“Doug’s summation in that meeting, between Earlham and the Conner Prairie representatives, of the nature of the legal relationship between Earlham and Conner Prairie, the terms of the Lilly gifts and the course of the events that had led up to that point in the relationship and his articulation of the issues of equity and fairness presented by Earlham’s proposal was one of the finest exercises in legal advocacy that I encountered during my career,” Duck said.

When the ultimatum was refused, Earlham fired the board. However, the members regrouped, formed “Save the Prairie” and were eventually able to secure Conner Prairie’s independence. Church is now able to enjoy the result of his work by wandering the grounds of Conner Prairie and listening to youngsters chatter excitedly about churning butter or throwing axes.

In a reminder that Church had three other job offers and could have gone anywhere, Rowland said Hamilton County was the beneficiary of his decision to remain.

“I think you would have made a great president of the United States,” Rowland said. “I always thought that, but we’re all very happy that you stayed right here next to all of us and shared your talent and your vision to make us the best we could be.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.