Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe meetings, the explaining, the drafting and redrafting, the arguments, the persuading, and the strategizing that went into the Bayh-Dole Act came down to a 15-minute window. On Nov. 21, 1980, the last day of the 96th Congress, then-Indiana Sen. Birch Bayh was given an opening to introduce the final version of the bill to the full U.S. Senate.

However, the Hoosier Democrat was away from his office on Capitol Hill and could not get to the Senate floor in time. Joe Allen, Bayh’s staff member who had taken the lead on crafting and shepherding the legislation, was despondent. His boss had lost the election and was preparing to leave office, so the bill designed to make a key change to the patent system likely would become a footnote rather than a law.

However, the Hoosier Democrat was away from his office on Capitol Hill and could not get to the Senate floor in time. Joe Allen, Bayh’s staff member who had taken the lead on crafting and shepherding the legislation, was despondent. His boss had lost the election and was preparing to leave office, so the bill designed to make a key change to the patent system likely would become a footnote rather than a law.

Then Allen saw the bill’s other author, Bob Dole, exiting the Senate Cloakroom. He grabbed the Kansas Republican and told him what was happening. Dole walked into the Senate and introduced the bill, which passed with unanimous support.

In the more than 21 million minutes following the bill being signed into law on Dec. 12, 1980, the Bayh-Dole Act has been credited with resparking innovation in the United States. Proponents say the act, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, revitalized the American economy and has brought products and pharmaceuticals to market that have improved lives around the world.

“The idea of Bayh-Dole was rather than having Washington bureaucracy manage something they didn’t know anything about, we said, ‘Let the people who made the invention manage it,’” Allen said. “… I think we were pretty confident that the Bayh-Dole model worked but we never would have predicted that it’s had the impact it’s had.”

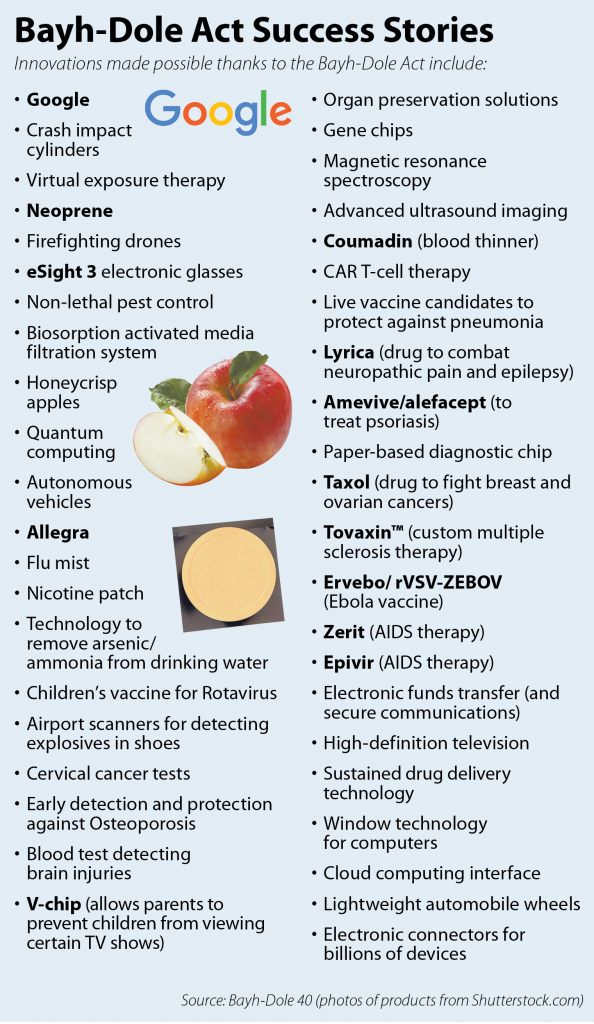

From 1996 to 2017, the Bayh-Dole Act contributed $865 billion to the U.S. gross domestic product and supported 5.9 million jobs, according to AUTM and the Biotechnology Innovation Organization. Numerous inventions including Google, Honeycrisp apples, firefighting drones, flu mist, breast and ovarian cancer medication Taxol, and high-definition television were all made possible by the legislation.

The law allows universities, small businesses and nonprofits that receive federal funding for research to retain the title to the patents on the innovations they create.

Previously, the federal government took the title and kept the inventions in the public domain. Companies and individuals had no incentive to invest the time and money developing the intellectual property into a marketable product because they could not get exclusive license to the patents. So, any competitor could swoop in after the hard work had been completed, copy the device or drug and profit from it.

As a result, the technologies discovered in academic labs were put on a shelf instead of being used.

“Sen. Bayh really saw this as an issue where people were suffering needlessly because we were destroying the incentives for bringing technology that the public had helped pay for,” Allen said. “They were just sitting there benefiting nobody and it just didn’t make any sense to him.”

Still, others were not keen on allowing the private sector to gain exclusive rights to publicly funded innovations. Sen. Russell Long, chair of the Senate Finance Committee, Admiral Hyman Rickover, known as the father of the nuclear navy, and consumer activist Ralph Nader were among the opponents who did not like the prospect of companies and individuals making money from something taxpayers paid for, Allen said.

Also, Bayh-Dole was running counter to the prevailing economic thought. The act spurred startups that have fueled the economy, but in the late 1970s, “cowboy entrepreneurs” and small businesses were seen as cute but not viable, Allen said. Many believed America should model its economy on the Japanese system that focused on big industry and big government.

Attorney Christopher Bayh, son of Birch Bayh, sees the effort put into the bill as his father’s response to America losing its standing in the world. The elder Bayh grew up during the Depression, served in Germany as part of the Marshall Plan and arrived in Washington at the start of the Great Society. Then the U.S. economy stalled while Japan and Germany, countries that had been devastated during World War II, began moving ahead.

“I think that’s why (the Bayh-Dole Act) was so important for my dad and what made it so important for Bob Dole,” said the younger Bayh, a partner at Barnes & Thornburg in Indianapolis. “I’m sure my father and Sen. Dole agreed on few initiatives, but a thriving American economy and American excellence, I’m sure they very much held that importance in common.”

Boilermaker innovations

The legislation started at a meeting that included Ralph Davis from the senator’s alma mater, Purdue University, according to Allen. Davis and others explained how patents were being taken from universities and innovations were never being developed.

“I found out that we had 28,000 inventions on the shelf; very few were even licensed, much less developed,” Allen said of his research after the meeting. “I also found out, to my shock, that not a single drug had been developed from (National Institutes of Health) funding because of these policies.”

Today, Purdue stands as an example of how the Bayh-Dole Act turned the situation around.

The Purdue Office of Technology Commercialization, part of the Purdue Research Foundation, has patent attorneys paired with business managers who evaluate the discoveries and innovations presented by professors and graduate students. Any intellectual property with potential is patented and licensed to the private sector.

Licensing agreements typically grant the licensee the right to use and sell the technology. In addition to requiring the innovation be developed, the arrangements also contain various methods for compensation like an upfront fee or milestone payments. Royalties could also start once the product reaches the market.

As the money flows back to Purdue, it is reinvested into developing more intellectual property. A third goes to the inventor, another third goes to the university department where the inventor works and the final third goes to the Trask Innovation Fund, a competition to support new discoveries.

Brooke Beier, vice president of the Purdue OTC, said the goal is to make sure the licensing agreement is a win-win for the university and the private company.

According to the OTC, the number of patent applications filed has risen from 471 in fiscal year 2014 to 721 in fiscal year 2020. The gross revenue climbed from $8.13 million to $13.6 million during the same period.

The cycle at Purdue illustrates what attorney Brian O’Shaughnessy describes as the ecosystem created by Bayh-Dole.

O’Shaughnessy, partner at Dinsmore & Shohl in Washington, D.C., and past president of the Licensing Executives Society, said private industry is now tapping into university expertise because of the act. This in turn sustains the higher education research structure that fuels discoveries that contribute to America’s economic growth and dominance in certain markets.

“So, we’re not just producing new chemical entities as drugs,” O’Shaughnessy said. “We’re producing many more Ph.D. researchers who are … producing more and more innovations, which are producing advancements in science for the benefit of society as a whole.”

March-in rights

Purdue chemistry professor Philip Low has more than 340 patents, mostly focused on drug therapies for conditions ranging from cancer and sickle cell disease to bone fractures. His research receives some NIH funding, and the resulting patents are owned by the Purdue Research Foundation.

Low has licensed his patents back to himself and, with venture capital support, has created seven startups. He remembered when he helped launch his first company, Endocyte, in the mid-1990s, officials at Purdue were hesitant to allow him to move forward, but now he is often asked to advise other faculty who are starting their own small companies.

In October 2018, Endocyte was sold to Novartis AG for $2.1 billion.

Low pointed out his companies grow to hire employees, typically Ph.D.-level researchers, which boosts the state and local economy. In addition, his startups are developing drugs that improve patients’ health and lives.

“There’s an awful lot of satisfaction that comes in founding or building an institution that leaves a footprint on the planet,” Low said. “I like starting from scratch with nothing but an idea.”

The money flowing through the pharmaceutical industry has prompted calls for the federal government to use the Bayh-Dole Act to control the prices of prescription medications. In the law is a provision that allows the federal agencies in narrow circumstances to “march-in” and essentially take control of the license if the intellectual property’s ability to benefit society is not being fully developed.

At a hearing in 2004, various groups pressed the Department of Health and Human Services to exercise the march-in rights after Abbott Laboratories hiked the price of an AIDS medication 400%.

Bayh testified that lowering the cost of the drug through the march-in rights would be wrong. “… Bayh-Dole permits march-in rights, not to set prices, but to ensure competition and to meet the needs of our citizens,” he said.

O’Shaughnessy said that prior to Bayh-Dole, no federally funded compounds developed by universities were being commercialized. Since the law was enacted, more than 300 compounds have been turned into meaningful, useful and effective pharmaceuticals.

“If the government ever uses march-in rights in the manner that some are promoting right now, it would be devastating to our innovation ecosystem,” O’Shaughnessy said.

After Bayh-Dole passed Congress, it went to the White House, where President Jimmy Carter signed the measure on the last possible day before it would have been pocket vetoed. The law was among Bayh’s proudest achievements.

“Birch Bayh really cared about people,” Allen said. “I saw him in action both in public and private and that was his real driver. He was in office to try to make people’s lives better and this issue just resonated with him.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.