Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWith the search underway for only the third director of the Indiana Supreme Court Disciplinary Commission, one thing seems certain: The court will take its time finding a successor for retired leader G. Michael Witte.

But interim director Robert Mrzlack made another thing clear: That person will not be him. “Interim,” he stressed, “is the correct title.” The retired judge of White Superior Court was appointed in a Feb. 2 order with the understanding, he said, that his service was on a temporary basis.

Mrzlack said he also will have no role in the selection of Witte’s successor, which will free him to focus on the day-to-day business of the commission staff — which he likens to a small law firm — some of whom may be candidates for the director position.

“I came in here blind,” Mrzlack said, noting he’s been working full time since Feb. 8, advancing cases while overseeing the office’s 11 attorneys, four administrative staff members, two law clerks and single investigator. “I’ve been very impressed with the professionalism of the staff.”

He’s also learned, “It’s not an easy job. No lawyer wants to get any type of correspondence from the disciplinary commission, so just that letter, that envelope, puts you on edge.”

Balancing responsibilities

Chief Justice Loretta Rush and commission members have definite ideas for what they want to see in the next director. Rush noted the director’s varied duties and responsibilities call for someone with broad skills, legal knowledge and sound judgment, but also some important intangibles.

“We are also looking for a candidate who has the respect of their peers,” Rush said in an email. “This is a position of great authority in the legal profession, a profession where we self-regulate. … The best candidate will be a lawyer the bar is proud to have in this position.”

Commission chairman John L. Krauss noted the director’s role is among the most critical in the court structure. “That person has to be a leader and an important, integral member of that family and work with a team,” he said.

Beyond overseeing discipline for alleged attorney misconduct, Krauss said the director is responsible for educating the public about the role of attorneys and offering ethical guidance to members of the bar. He repeatedly used the word empathy — “empathy and common sense in the law” — as critical qualities for a director.

“The relationship the attorneys have to the courts and the clients is one of trust, and the commission is a body that’s supposed to be enabling the trust to occur, and hopefully we’re seeing an opportunity that can be improved over time,” he said.

Taft Stettinius & Hollister partner Andi Metzel has served nearly 10 years on the commission. “My personal vision of an ideal candidate is one who is forward-thinking, engaged and dedicated to improving the administration, conduct, fairness and best practices of the commission — at every stage — to safeguard public confidence in Indiana’s disciplinary system,” she said in an email.

“For me, protecting the public is not just about lawyer discipline, it includes educating lawyers and encouraging competence and ethical conduct throughout the bar.”

Commission member Kirk White of Bloomington said a director must juggle managerial demands, overseeing investigations, making recommendations to the court on disciplinary matters, interpreting the rules of professional conduct and staying current on trends and guidance to the bar.

“It’s a challenge to find a person who can do all those things,” he said.

Ultimately the justices will choose the next director with input from commission members, the Office of Judicial Administration and others. Supreme Court spokeswoman Kathryn Dolan described a process that will involve multiple rounds of candidate interviews and background checks. The court declined to say how many people applied or when a new director may be named.

Tough cases

Commission members emphasized they are bound by confidentiality rules that prevent them from discussing individual cases, but some responded to observations that several recent disciplinary decisions have resulted in the court finding no misconduct. Those include ethics cases against Knox County Prosecutor J. Dirk Carnahan, Putnam County Prosecutor Timothy Bookwalter and Barnes & Thornburg partner Larry Mackey.

Commission members emphasized they are bound by confidentiality rules that prevent them from discussing individual cases, but some responded to observations that several recent disciplinary decisions have resulted in the court finding no misconduct. Those include ethics cases against Knox County Prosecutor J. Dirk Carnahan, Putnam County Prosecutor Timothy Bookwalter and Barnes & Thornburg partner Larry Mackey.

Krauss said the commission functions much like a grand jury, hearing claims of misconduct and forwarding its recommendations to the court: “Here are the facts and here’s what we’ve found, preliminarily.”

“Our job is determining probable cause” of a potential ethics violation, he said. “… (I)t’s for others to try the case, hear the other side with more evidence that will come forth, and it’s up to the court to make a determination. … The other thing is, I don’t think we take anything lightly.”

Members said the commission works to reach a result all are comfortable with, but the seven lawyers and two nonlawyer members aren’t always unanimous. That’s partly because of the nature of the cases they’re dealing with — some, such as criminal convictions, are clear on their face, while others may be misunderstandings rather than unethical conduct.

“Some are more complex than others, like any other legal situation,” said White, a nonlawyer member. “We often have spirited discussions.” He said the commission receives and discusses the Supreme Court’s final disposition of cases, but he said he’s seldom surprised if the result is a ruling in favor of a respondent.

“As investigations are done, new facts and perspectives are brought to light, and there are always going to be differences and things that change after we look at things,” he said.

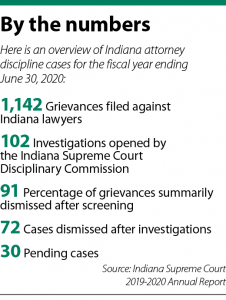

Mrzlack said every complaint, whether from an inmate, a judge or another source, is screened. Routinely, about 90% are summarily dismissed.

Mrzlack said he was struck by the number of attorneys getting into trouble because their trust accounts don’t add up, or worse. “We’re seeing attorneys getting arrested for felony offenses and misdemeanors routinely,” he said.

Krauss pointed to a growing source of discipline complaints for Indiana attorneys: “Social media is a bottomless rabbit hole,” he said. Lawyers, he said, “need to understand the implications of that for your professional practice.”

In a number of cases — 12 in fiscal year 2018-19, according to the commission — lawyers were suspended for noncompliance with a commission investigation of allegations of misconduct. For some of them, it’s the end of their legal career.

“I don’t understand that thought process, necessarily,” Mrzlack said of lawyers who don’t respond to commission investigations. “Ignoring it and choosing not to participate usually doesn’t end well for the attorney.”

Krauss likewise is troubled by those cases, especially because in many cases attorneys could avail themselves of help from the Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program or other court services. “Sometimes they’re embarrassed and they don’t want to admit something,” he said, but ignoring the problem forces the commission’s hand.

“You hope you don’t have to use the sledgehammer” of a noncompliance suspension, Krauss said.

“When a person comes in and says, ‘I did this, I know I have a problem,’” he said, “we’re going to look more favorably upon that person than somebody we are going to have to go find, and it’s refreshing to see honesty.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.