Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAt the start of 2018, the end seemed to be in sight for salad lovers after a multistate E. coli outbreak contaminated leafy greens. At least one death was reported, and 25 people were sickened, including two Hoosiers.

But in March, a similar strain was detected in a batch of romaine lettuce traced back to Yuma, Arizona. That outbreak ultimately sickened more than 200 people across 36 states, ending with 27 cases of kidney failure and five deaths.

Then in November, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned consumers about romaine lettuce harvested in parts of northern and central California after a third E.coli outbreak was confirmed. Since November 20, there have been 43 reported cases and 16 hospitalizations from the outbreak.

Around the same time, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration released its Nov. 1 environmental assessment of potential contributors to the Yuma outbreak. It found that a large concentrated animal feeding operation — better known as a CAFO — was located adjacent to the same canal used to irrigate fields where the romaine lettuce was grown. Although the FDA noted that the limited number of samples taken at the CAFO did not yield that specific E.coli outbreak strain, the FDA did not offer any other possible explanations for the contamination.

Whether that CAFO played a role in contaminating the irrigation canal — and what that might mean for consumers and farmers — are lingering questions.

Could it happen here?

Those closer to home wonder, could such contamination happen in the Hoosier state?

“It’s certainly an unusual situation,” said Indianapolis agriculture lawyer Todd Janzen. After working in the ag law field for almost 20 years, Janzen said he doesn’t think such water contamination concerns are likely to occur here.

“We don’t have a lot of irrigation from canals or ditches,” he said. “Most of our irrigation comes from irrigation wells which pump groundwater, and I haven’t seen instances of ground water contamination from manure applications on fields.”

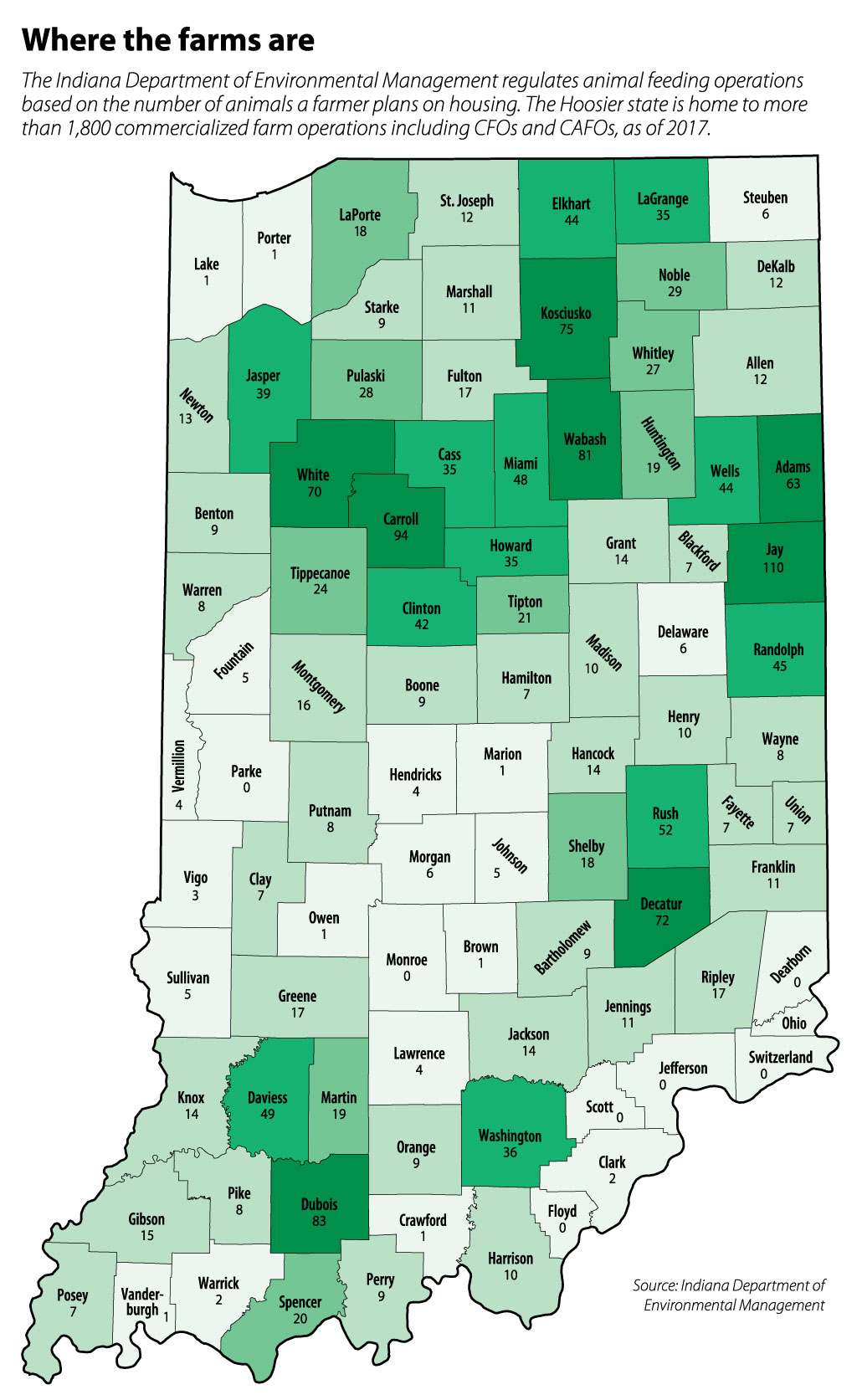

Manure utilized by Hoosier farmers typically comes from one or more of Indiana’s 1,800 commercial animal feeding operations across the state, which are regulated by the Indiana Department of Environmental Management.

That number encompasses CAFOs, which house large numbers of livestock or poultry — more than 700 dairy cows, 1,000 head of other cattle, 2,500 swine above 55 pounds, or 10,000 swine less than 55 pounds.

It also includes CFOs, a similar animal feeding operation on a slightly smaller scale — 300 or more cattle, 600 or more swine, and 30,000 or more poultry.

Janzen said in Indiana it’s illegal to dump any livestock urine or feces into ditches or streams. There are regulations set in place by the Indiana Department of Environmental Management that are intended to prevent water contamination, he added.

“If it’s a swine farm, the manure will be kept in a pit which is enclosed and no rain water or elements get in there because it’s under the barn,” Janzen said. “They also design those with a perimeter tile drain around them to keep groundwater away from the facility.

“For dairy operations, where manure is often kept in outdoor lagoons, those also often have perimeter drains around them that are a secondary warning if you were to have anything escape,” he continued. “They’re also required to have two feet of additional room on the top that you’re never allowed to fill.”

Janzen said that extra two feet serves as a buffer in the event of massive rainstorms, preventing overflow into surrounding fields and land. The stored manure is periodically used to fertilize fields, which CAFO opponents argue can wash away with runoff water or leach into groundwater used by surrounding communities.

But Janzen said IDEM rules are specific on how close CAFO farmers can put manure on a field near any ditch or exposed surface water or groundwater wells.

Different crops, different consumers

Different crops, different consumers

With experience growing up on his family’s farm, Indianapolis agribusiness attorney Adam Kline agrees that it’s unlikely that Indiana would suffer from an E.coli outbreak like Yuma’s.

“Mainly because we don’t have many vegetable or fruit crops in the state,” Kline said. Unlike other states with climates more suitable for growing ready-to-eat products such as lettuce and fruits, Kline said the majority of Indiana’s crop consists of corn and soybeans, which use a different irrigation system.

“And the beans and corn are not usually for human consumption,” he added. “It’s usually used for feed for the animals or for use in other products.”

That’s true for Putnam County hog and commodity crop farmer Mark Legan, who said he feeds his sows the corn produced on his fields. Any waste created by his 2,200 sows is collected in deep pit tanks below their barns, which is later injected through a tube roughly 6 to 8 inches below the surface of the soil to fertilize the fields.

Housing livestock in larger, confined barns, he added, also prevents environmental damage from waste runoff and potential contamination.

Legan said his 30-year-old family farm, which is categorized as a CFO, takes environmental stewardship seriously and utilizes best practices and sustainability.

“We’ve got to be efficient and take care of the environment and our animals and people,” Legan said. “We live on this farm. We’re drinking the groundwater. We’re concerned about what we do and how we do it.”

But Hoosier Environmental Council senior staff attorney Kim Ferraro said not all farmers follow best practices.

“You can’t make general statements based on one example where there potentially isn’t a concern,” Ferarro said. “Certainly there are those out there that are doing it right. Injection is one way to ensure that the waste gets incorporated into the soil for plant use, but you still are going to have the problem if you over-inject, over-apply that waste.”

She said if too much waste is applied, the excess could run off into nearby surface waters or leach into groundwater. Then the possibility for E.coli contamination is present.

Based on her understanding of the science, Ferraro believes many E.coli outbreaks that occur stem from livestock waste.

“Is it always the case? No, I can’t possibly say that,” she said. “But we do know it’s happening much more frequently and typically it’s being associated with livestock waste.”

Janzen said he’s unsure of what the outcome will be concerning the FDA’s hypothesis regarding a connection between the Yuma E.coli outbreak and its neighboring CAFO. But what he does know is consumers need to be conscientious about their food.

“I would say if you’re using any sort of animal waste on a produce that you eat, you have to be very careful,” he warned. “If you’re using it as a fertilizer, you have to be very careful so that you don’t have this problem occur.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.