Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIndianapolis attorney Robbin Stewart was raised to value the right to vote.

In his home state of Delaware, Stewart watched his mother work as a citizen lobbyist to protect the environment, and he got his first taste of political activism when as a 10-year-old he joined the campaign of a man running for state representative. He earned his J.D. degree in 1993 at the University of Missouri School of Law and then completed an LLM on state constitutions and voting rights at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

However, since 2005, when Indiana started requiring voters to show their picture before casting a ballot, Stewart has had trouble. He wants to vote, but he does not want to show his photo ID.

Stewart filed federal lawsuits in 2008 and 2010 and lately has started recording videos of what happens when he declines to show his driver’s license to poll workers. To date, his efforts have been in vain. Federal courts have dismissed his previous complaints, and his votes have largely gone uncounted.

Wearing a suit coat with blue jeans and what appear to be Chuck Taylor sneakers, Stewart said his skills as an attorney are limited, especially for the work some may consider to be tilting at windmills, but he has no plans to quit. He has another lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, Robbin Stewart v. Marion County Election Board, et al., 1:18-cv-01487, and is attempting, again, to cast a valid vote without an ID.

“I’m a little bit crazy,” Stewart said, “and I’m a little bit this well-educated lawyer with a really deep traditional sense of what my rights are under the state Constitution.”

“I’m a little bit crazy,” Stewart said, “and I’m a little bit this well-educated lawyer with a really deep traditional sense of what my rights are under the state Constitution.”

Indiana, like many states, has been amending and enacting new voting laws in the name of stamping out voter fraud. Stewart is not the only one noticing and challenging these efforts.

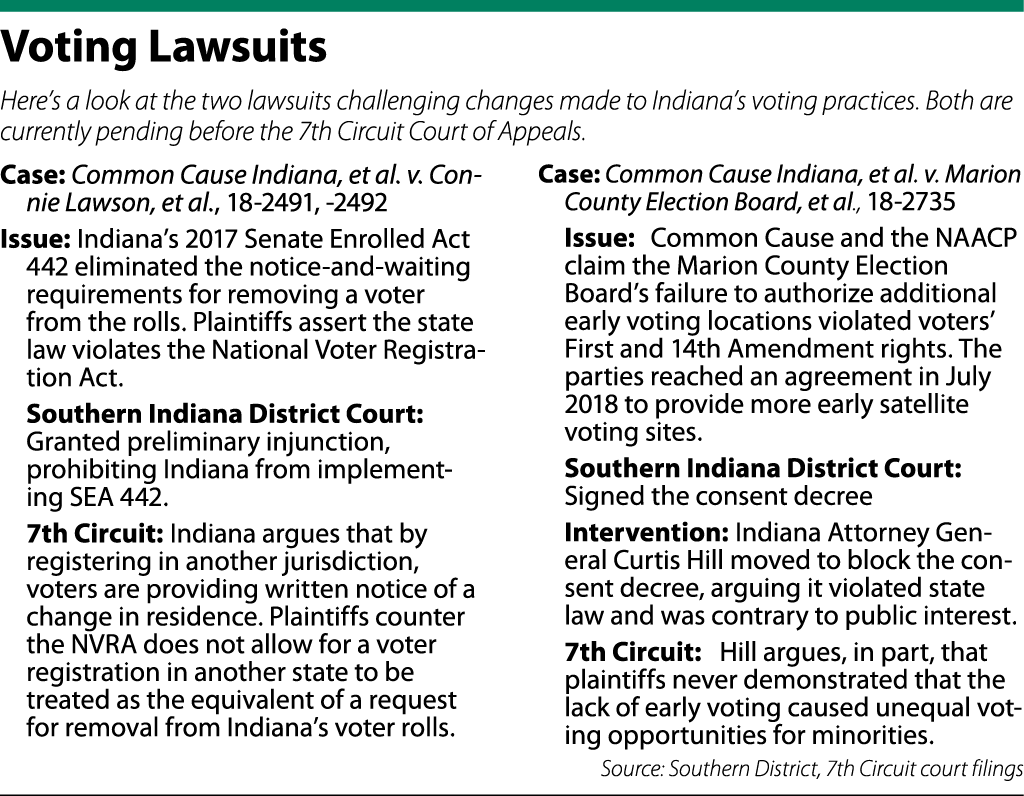

Common Cause Indiana, the League of Women Voters of Indiana and the Indiana State Conference, as well as the Greater Indianapolis Branch 3053 of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, have filed complaints in federal court. So far the groups have won favorable rulings in Southern Indiana District Court, but the two cases are on appeal to the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals.

The first lawsuit, Common Cause Indiana, et al. v. Connie Lawson, et al., 18-2491 and -2492, is challenging the change to state law that enables individuals to be removed from the Indiana voting rolls more quickly. The second lawsuit, Common Cause Indiana, et al. v. Marion County Election Board, et al., 18-2735, successfully pushed for more early satellite voting sites in Marion County.

Both cases are still being briefed at the federal appellate court, and as of IL deadline, oral arguments had not yet been scheduled in either case.

Appellate fights

The lawsuit over the voter rolls was started when the Indiana General Assembly passed Senate Enrolled Act 442 in 2017. Common Cause, the NAACP and the Indiana League of Women Voters saw the new law as violating the National Voter Registration Act’s requirements for notice-and-waiting procedures.

In particular, the plaintiffs contend SEA 442 permits counties to remove voters flagged by the Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck program without providing notification or waiting through two general election cycles to see if the individuals voted. Noting Crosscheck has been criticized for being inaccurate, the parties claim the safeguards against removing eligible voters are not robust, and most counties “simply rubberstamp” the results of Crosscheck.

The Southern Indiana District Court granted a temporary injunction prohibiting Indiana from implementing SEA 442.

Before the 7th Circuit, Indiana is arguing that Crosscheck does not violate the NVRA. The national act allows election officials to cancel a voter registration without notice or a waiting period when the registrant has confirmed in writing that he or she has moved out of the jurisdiction. Registering in a new state, Indiana asserts, constitutes a request to cancel a prior voter registration.

Indiana Secretary of State Connie Lawson has said that when she came into office in 2012, the state’s voter rolls had not been maintained and many outdated registrations were still on the list. In April 2017, she announced that 481,235 voter registrations had been cancelled.

Between 2013 and 2016, the Crosscheck program was used to supplement Indiana’s own voter registration maintenance, according to the Secretary of State’s office. “No voters have been removed from Indiana’s rolls,” the Secretary of State’s office said. “Instead, inaccurate and outdated voter registration records have been removed.”

As the state was filing its notice of appeal with the district court, Indiana Attorney General Curtis Hill sparked a firestorm in August 2018 when his office objected to the consent decree Common Cause and the NAACP reached with the Marion County Election Board, which established more early satellite voting sites. The Attorney General submitted a brief to the 7th Circuit that argues the plaintiffs never demonstrated the lack of early voting sites created unequal voting opportunities for minorities.

Moreover, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 does not condemn voting practices solely because it has a disparate effect on minorities. Citing Frank v. Walker, 768 F.3d 744, 753 (7th Cir. 2014), the Attorney General asserts, “Rather, to run afoul of the Voting Rights Act, the voting practice must afford less opportunity for minorities to vote. Even causing a disparate impact does not prove less opportunity; it proves at most that minorities use the opportunity less.”

The briefs from Common Cause and the election board are due Jan. 15, 2019.

Changing focus

Stewart began his battle by fighting against Indiana’s voter I.D. law. When the case questioning the constitutionality of Indiana’s photo requirement, Crawford, et al. v. Marion County Election Board, et al., 553 U.S. 181 (2008), was argued before the United States Supreme Court, Stewart joined an amicus brief filed by privacy advocates and civil liberty groups including the Cyber Privacy Project and the U.S. Bill of Rights Foundation.

To Stewart, having to present a photo ID in order to exercise the right to vote runs afoul of the U.S. and Indiana constitutions. He argued the law violates the rights to due process and equal protection, as well as constitutional rights against warrantless searches.

However, since the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Indiana’s voter ID law, Stewart has changed his focus. Now he is working to make a record to show the law is not being followed when he declines to present his photo on Election Day. Under Indiana statute, voters who do not show their picture are to be given a provisional ballot and allowed within the next 10 days to prove their identity to either the circuit court clerk or the county election board.

Stewart maintains the Supreme Court was swayed to support the voter I.D. law because of the touted failsafes. Things like being allowed to cast a provisional ballot and getting a photo ID for free convinced the majority of justices, he said, that eligible voters would not be disenfranchised.

Pointing to his own experience, Stewart asserted that in practice, the election officials are not abiding by the law and voters who do not have proper identification are being prohibited from casting any kind of ballot.

Data from the Indiana Secretary of State’s office gives the totals of provisional ballots but does not provide any explanation for why the provisional vote was made. In November 2016, 800 provisional ballots were cast and 454 were counted, while 577 were cast in November 2018 and only 196 were counted.

Stewart was given a provisional ballot for the November 2018 midterm election, and he was prepared for the election board hearing to prove he is Robbin Stewart with affidavits and non-photo documents, like his bartender’s license and bank statement. But he never got his chance to convince the county to accept his identity and count his ballot without seeing his picture because, according to him, the hearing time was changed and he was not given notice.

Stories of votes being cast by ineligible individuals or even dead people have spurred the movement to narrow the path to the polling place. Although election tampering by voters has historically been rare, states contend they must act to prevent fraud at the ballot box.

Stewart takes a more expansive view. “I would argue not counting my ballot is voter fraud,” he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.