Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now Andrea Kiefer was waiting for a green light to start her work as an independent paralegal. But instead she faced a roadblock.

Andrea Kiefer was waiting for a green light to start her work as an independent paralegal. But instead she faced a roadblock.

The Indianapolis entrepreneur recently left her full-time paralegal position at a law firm to start her own freelance company after spending years employed by various firms. As excited as she was to get the ball rolling, Kiefer had questions that left her apprehensive.

“As I started talking with more paralegals, I kept hearing, ‘Don’t you know about people’s confusion with Guideline 9.1? You may not be allowed to be a paralegal in Indiana on contract,’” she recalled. “I was holding off on doing a large marketing campaign for that very reason. I didn’t want to spend hundreds of dollars to have it tossed in the trash.”

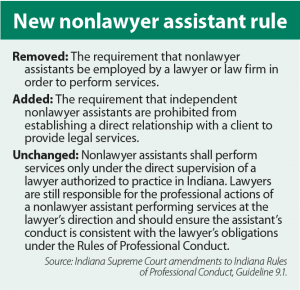

Under the Indiana Rules of Professional Conduct, Guideline 9.1 addresses the supervision of nonlawyer assistants. The guideline formerly required nonlawyer assistants to be an employee of a lawyer or a law firm in order to perform paralegal services. Under that language, Kiefer didn’t feel comfortable offering her services on a freelance basis.

There was an increased hesitancy to do so, she noted, after the Indiana Supreme Court suspended a northern Indiana attorney in 2017 for violating numerous professional conduct rules, including Guideline 9.1. In In the Matter of: Doug Bernacchi, 46S00-1512-DI-694, the Michigan City attorney agreed to take a child support case in which he instructed the client to pay an $800 nonrefundable retainer in full to Mario Sims, an independent contract paralegal. Bernacchi also indicated to his client that he would collect his portion of the funds from Sims. Any questions the client had about the case were to be directed to Sims, and Bernacchi later admitted he had never even met the client.

Justices concluded Bernacchi committed attorney misconduct in part by improperly using and splitting his fee with Sims, and ultimately suspended the attorney for one year without automatic reinstatement.

“It made some in the legal community think that maybe this shouldn’t be something that paralegals should be doing,” Kiefer explained. “But now there’s no confusion. The cloudy gray areas are no longer there.”

Free to freelance

The air for Kiefer was cleared when the Supreme Court amended Guideline 9.1 last month, removing the requirement that independent nonlawyer assistants be employed by a lawyer or law firm in order to offer their services. The changes came in response to a resolution passed by the Indiana State Bar Association House of Delegates and proposed by the ISBA Legal Ethics Committee. Their suggestion requested the removal of the employer requirement, so long as the nonlawyer assistant’s supervising lawyer would take reasonable measures to ensure the assistant’s conduct was consistent with the lawyer’s obligations under the Rules of Professional Conduct.

Ethics Committee chair Steven Badger said the suggested changes were needed to clarify and clean up the guideline’s language to keep Indiana from being an outlier with other states.

“It was a pencil trap because we know a lot of practitioners use independent contractors. It’s not uncommon at all, for example using a paralegal to help with discovery. Lawyers do that a lot,” Badger said.

The use of independent contractors is beneficial to both clients and lawyers, Badger added, particularly those who practice in small firms and solo shops.

“It gives them more flexibility and delivery of low-cost services to clients,” he said. “It makes their work much more efficient. Rather than doing it myself at a lawyer’s rate, I can hire a paralegal to do it at half that rate.”

Having the ability to utilize the services of independent nonlawyer assistants on a per-job basis is critical for solo and small firms, said committee member and solo attorney Don Lundberg. The change, he added, is a welcome one for those practitioners who rely on flexibility.

The former Barnes & Thornburg LLP attorney said large firms have the luxury of a pool of employed paralegals to work with when needed.

“It’s small firms and solo lawyers who basically say, ‘Look, I don’t need and I can’t use a full-time paralegal. It doesn’t make economic sense for me to have to employ a paralegal,’” Lundberg said.

Solo attorney Jason Massaro agreed. Massaro said that while he is not in a position where he needs to utilize the services of an independent nonlawyer assistant, he can certainly understand the concerns of those who do.

“It allows better client service without having to penalize all other clients by maybe passing along a cost that’s not associated with their case,” Massaro observed of the amended guideline. “If I’m forced to employ someone on a sporadic occasion, someone has to bear the cost of that. But it’s no longer an issue.”

Another pothole

As it was previously written, Massaro said, Guideline 9.1 could have potentially chilled an attorney’s ability to receive extra help from someone on an independent contract capacity. But with that issue no longer on the table, Massaro said the amendment seems to have traded one problem for another.

The amended guideline also includes new language that states, “Independent nonlawyer assistants are prohibited from establishing a direct relationship with a client to provide legal services.”

“I’m all in favor of what was struck from the rule, and I’m not in favor of what was added,” Massaro said. In his opinion, the additional language creates further ambiguity by not including context as to what defines a direct relationship. “It’s anybody’s guess as to what that means,” he said.

ISBA Litigation Section Chair Jaime Oss said that while she’s very excited about the employer requirement removal, she, too, has concerns about the additional language.

“That’s an issue,” Oss said. “We don’t know whether that phrase is defined broadly or not. What exactly does that mean?”

From her interpretation of the professional rules and guidelines, Oss opined that perhaps “direct relationship” refers to not accepting money from a client or not acting as the primary contact for the client.

“I think there are lawyers who would like that to be qualified who use the independent nonlawyer assistants, just so no one accidently runs afoul in allowing their nonlawyer assistant to do too much,” she added.

Massaro said he thinks the confusion could be easily remedied by using Guidelines 9.2 through 9.10 as a reference.

“For example, 9.2 says that provided the lawyer maintains responsibility for the work product, a lawyer may delegate to a nonlawyer assistant or paralegal any task normally performed by the lawyer,” he said. “If that’s permissible in 9.2 but prohibited under 9.1 to have a direct relationship in order to offer services, those two, to me, don’t correlate.”

Green light

Nearly immediately after receiving word of the amended guideline, Kiefer launched into action.

“I was very excited,” she said. “Basically the very next day I went to the post office and sent off my first hundred marketing mailers.”

Despite lingering concerns, Keifer said she thinks the revised Guideline 9.1 is a win-win for attorneys and paralegals in the state that will have a positive impact on the legal community.

“Now I feel very comfortable about contacting every single attorney in the state and offering my services,” Keifer said. “This allows me to raise the bar personally and professionally. We’ve been given an amazing opportunity.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.