Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowEditor’s note: This story has been updated.

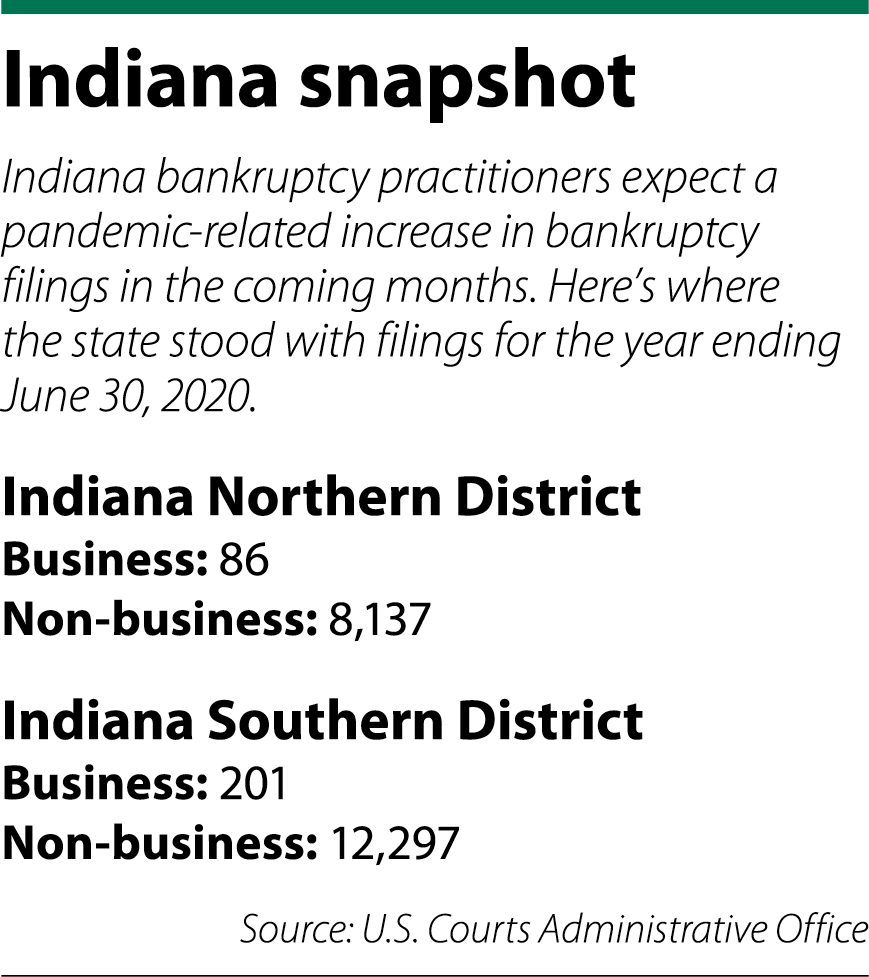

If you thought the COVID-induced recession would cause a spike in bankruptcy filings, you’d be wrong. At least for the moment.

In fact, according to one Indianapolis practitioner, “bankruptcies are in the toilet.”

The current economic downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic bears some similarity to last decade’s Great Recession, but it also has its differences, including the pace of bankruptcy filings. The Great Recession saw a near-immediate flood of filings, lawyers say, while various economic relief during the 2020 pandemic kept many Americans afloat, at least temporarily.

But that doesn’t mean bankruptcy practitioners are sitting idle, as existing clients still need their service. More than that, a wave of new clients is likely coming.

As government relief funds begin to dry up, many Americans will no longer be able to avoid the inevitable, bankruptcy practitioners say. That leaves one question: when will the inevitable strike?

“I think we’ve all been expecting a tsunami of filings,” said Jeff Hester of Hester Baker Krebbs in Indianapolis. “Everybody thinks, ‘Maybe this month, maybe this month,’ but it keeps not happening.”

Why the decline?

In years past, Jennifer Thornburg saw about 1,000 bankruptcy cases filed per month in the Indianapolis division of the Southern District of Indiana. Though that mark hasn’t been met for a while, she used to gauge the number of cases based on the month — in September, for example, case numbers often hit the 9,000s.

But on Aug. 31, Thornburg filed case 4,904.

“From that (2008) recession, cases are lower now,” said Thornburg, of Thornburg Law Office in Greenfield. “There wasn’t the help back then — the stimulus checks and those things.”

Bankruptcy practitioners across Indiana agree that federal relief funds are the driving factor behind this year’s low filings. In addition to the stimulus checks distributed in the spring, the government offered an extra $600 in weekly unemployment benefits. That meant more income than normal for some Americans, the lawyers said.

Additionally, federal and state governments, including in Indiana, instituted moratoriums on evictions and foreclosures. That relieved some of the pressure that often leads to bankruptcy, according Mark Zuckerberg, a solo practitioner in Indianapolis.

Businesses also benefited from federal assistance such as the Paycheck Protection Program and COVID-specific relief from the U.S. Small Business Administration. Thornburg’s own practice benefited from SBA assistance, she said.

What’s more, there’s a very basic explanation for the drop in filings, according to Thornburg: would-be clients don’t have the money to pay for bankruptcy proceedings. Zuckerberg’s clients have been going back to work, he said, but often they’re not bringing home the same income.

The reckoning

As the pandemic continues on, relief efforts seem to be slowing.

The $600 unemployment checks have stopped, and the $300 weekly benefit implemented in September won’t provide the same level of assistance. Additionally, Congress has so far been unable to agree on a second round of stimulus funding.

Also, eviction and foreclosure moratoriums are ending. And in the commercial arena, multi-tenant landlords are finding themselves stuck between their lenders who expect payment and their tenants who want payment relief, said Dustin DeNeal.

“Most of those relief options kicked the can down the road,” said DeNeal, of Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath. “I expect at some point there’ll be a reckoning.”

Already DeNeal is hearing from clients who know they are or will soon be unable to meet their financial obligations. To that end, he’s been busy helping those clients plot the best course.

Zuckerberg describes bankruptcy as a way to “help the honest but unfortunate.” Likewise, DeNeal sees bankruptcy as an effective tool, but only when used in the right context.

“Bankruptcy does not create income where income is not there in the first place,” DeNeal said. Businesses and individuals whose income streams are “irreversibly affected” by COVID-19 might not be suited for a bankruptcy proceeding.

Instead, a business might look into liquidation, DeNeal continued. That option could be appealing to small- and mid-sized companies, which often find bankruptcy to be too expensive.

It can be difficult, though, to know now what the best choice will be for a business that wants to succeed in a post-pandemic world.

“I compare it to a hospital — when you check into a hospital, you don’t know what you’re going to look like on the other side,” DeNeal said. “It’s tough to tell where you’re sitting right now when your check out date would be, and it’s tough to tell what you’ll look like post-coronavirus.”

When’s it coming?

Right now, DeNeal said he’s dipping his toes in the water of COVID-related bankruptcies. But eventually the flood will come.

Right now, DeNeal said he’s dipping his toes in the water of COVID-related bankruptcies. But eventually the flood will come.

Hester estimates a surge of filings coming late this year or early next. Thornburg agreed, opining that the flood could start in a matter of months. Zuckerberg thinks either October or February, though he’s not sure which.

Filings in Thornburg’s practice are usually cyclical, she said. Tax season tends to be a busy time, as people will often use tax refunds to fund their bankruptcy proceedings. The back-to-school season also usually presents a surge, she said, because parents have more time to consider their finances when children aren’t at home. The tax-based surge was just about to hit when the pandemic came to Indiana, she said.

Even now with courts reopening, there have been calls to make more bankruptcy judges available. A report released by the Harvard Law School Bankruptcy Roundtable recommended an additional 50 temporary bankruptcy judgeships in the best-case scenario, and an additional 246 judges in a worst-case scenario.

Zuckerberg’s concern is for the reintroduction of mortgage payments into people’s budgets. Many companies put mortgage payments in forbearance during the initial shutdown, but he stresses the importance of understanding what that means.

“Forbearance does not mean forgiven, forbearance does not mean modified — it just means forbearance,” he said. “At the end of these six months, a majority of people are going to have to pay again. That’s going to sink a lot of people.”

Another area of debt that concerns Zuckerberg is student loan default. He pointed to a Sept. 20 article in the Wall Street Journal showing that student loan debt has increased by more than 350% since 2003 in the total household debt balance. Comparatively, auto loans and housing debt have increased in the total household debt balance by around 50%, while credit card debt has decreased in the balance.

Further efforts

Though government relief is slowing, Zuckerburg still sees options. As it relates to student loans in particular, he noted that Congress has considered providing a debt discharge mechanism.

But absent such relief, the bankruptcy filings will come soon, lawyers say. Some industries may be hit harder than others, DeNeal noted, pointing to the retail, hospitality, tourism and food sectors.

Some bankruptcy practitioners themselves have faced business difficulties because of the pandemic, with Zuckerberg saying he’s had some sleepless nights in recent months because of the decreased filings. But he was comforted by a fact he knows other businesses can’t yet cling to.

“I know I’m going to be super busy soon,” he said. “But if you’re a downtown restaurant and nobody is downtown and nobody is eating, that may go on for the near future.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.