Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowFor child advocates and proponents of juvenile justice reform, it was the canary in the coal mine.

A bill that would have lowered the age at which a juvenile could have been tried as an adult was defeated only in the final days of the 2019 session of Indiana General Assembly. Senate Bill 279, introduced in response to the 2018 shooting at Noblesville West Middle School that seriously injured a student and teacher, would have allowed children as young as 12 to be waived to adult court if they were charged with attempted murder.

Currently, Indiana allows 12-year-olds charged with murder to be waived but requires that children be 14 before being eligible for waiver on an attempted murder charge.

Reform advocates have long worked in the Statehouse, and Indiana’s criminal justice systems – both adult and juvenile – have been making changes to rehabilitate offenders. Mental health treatment, positive school discipline practices and services offered in a family setting are much better at changing the behavior of children and young adults, reformers says, than harsh punishment. However, to them, SB 279 showed that progress can be tenuous.

“The fact that it got so far tells us we need a lot more community engagement on these issues,” said JauNae Hanger, attorney and president of The Children’s Policy and Law Initiative of Indiana. “The fact that this almost became law last year is quite an eye-opener.”

To that end, CPLI and more than 20 nonprofits and community groups have joined together to form the Indiana Coalition for Youth Justice. The coalition is advocating for reform in the juvenile justice system so that it offers treatment, programs and interventions that are age-appropriate, fairly applied and result in the best possible outcomes for Indiana children and public safety.

Revamping the juvenile justice system is a heavy lift for any organization, but the coalition – which includes We LIVE, Inc., the Marion County Commission on Youth, The National Council of Negro Women and Prevent Child Abuse Indiana, a Division of The Villages – is not deterred. It has crafted a detailed vision statement and has prepared a legislative agenda for the upcoming 2020 session of the Indiana General Assembly.

Hanger said organizations must band together to push for changes in criminal justice because, as they say SB 279 indicated, the current system “just doesn’t get it.”

“We’ve got to be more strategic and we’ve got to be looking long-term and really asking our legislators to be accountable for the investments they’ve made that are not working,” Hanger said. “They’ve invested in waiver and they’ve invested in detention and secure confinement for too many kids.”

Research, data, best practices

Looking at the data collected by the Indiana Criminal Justice Institute, Marcy Mistrett sees reason for alarm.

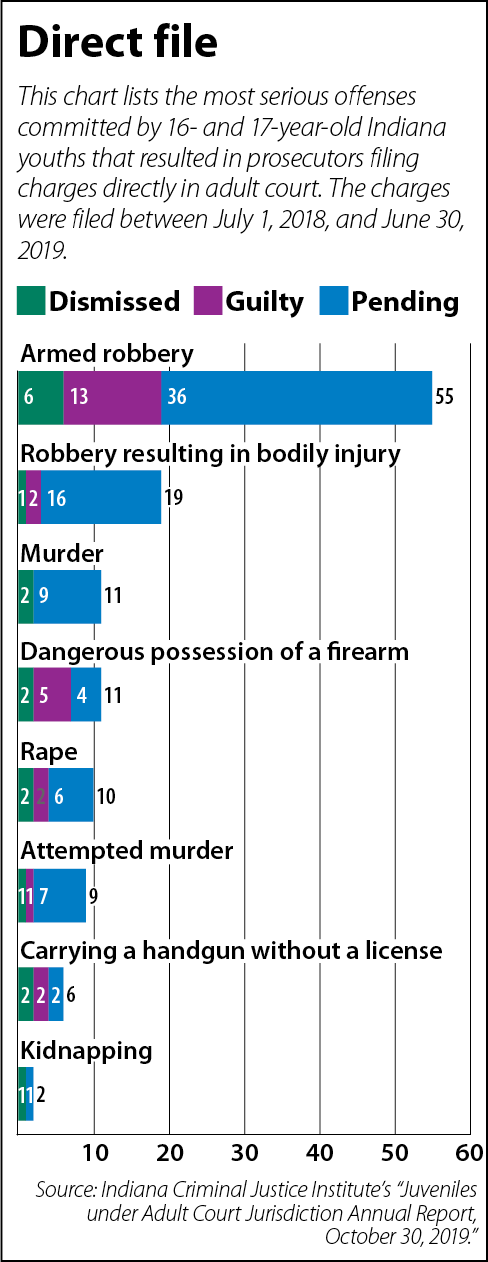

The CEO of the Campaign for Youth Justice pointed to a report from the Indiana Criminal Justice Institute which showed that 14% of the 156 juvenile offender cases waived to adult court in 2018 were ultimately dismissed, while the most common sentence was suspended. Similarly, more than 13% were also dismissed in 2019, and although the most common sentence was prison, just over 42% had a portion of their sentence suspended.

Mistrett sees the stats as an indication that Hoosier youths are being overcharged when they encounter the justice system.

“Look at who’s getting charged, with what and what the sentences are,” she said of Indiana. “It’s pretty alarming.”

From a career spent helping and advocating for youth, Mistrett cites reports and studies that bolster her professional experience that locking kids into secure facilities is not a productive deterrent. Their brains are still developing physically, and they are still maturing emotionally and intellectually, so services like counseling, trauma response and interventions have to be included when the justice system holds juveniles accountable, she said.

Mistrett has seen improvements in the juvenile justice system over the last 15 years that, to her, indicate attitudes about youthful offenders are shifting. In particular, she pointed to stats that show nationwide arrests are down to 40-year lows and, not coincidently, incarceration of children has dropped 55%.

“The country is doing very well in remembering that children are children and that the incarceration system really failed,” Mistrett said. “Incarcerating kids has led to nothing but bad outcomes all the way around for kids, the public and the victims.”

‘Children are children’

In crafting its legislative agenda, the coalition focused on the “children are children” sentiment. The goals for 2020 include eliminating the current practice of housing juveniles in adult jails pretrial and establishing a minimum age below which they cannot be detained in a juvenile facility.

Currently, Hanger said, juveniles awaiting trial are held in adult facilities and are placed in a juvenile center only after they are sentenced. Moreover, Indiana has no age limit on detention, and children as young as 9 have been sent to detention centers.

The potential that 12-year-olds could face adult punishment for attempted murder galvanized Rev. Ivan Douglas Hicks, cofounder of the Ministerium, to rally opposition to SB 279. His community group attended committee hearings on the bill, talked to legislators and hand-delivered a thousand letters to the Statehouse.

Hicks’ concerns included the disproportional impact a lower age of waiver for attempted murder might have on minority youths. Preteens from disadvantaged backgrounds might not have the resources to defend against the charge, which, he worried, could mean SB 279 “would be greasing the pipeline to prison.”

The 2019 Juveniles under Adult Court Jurisdiction Annual Report from the ICJI highlighted the disproportionality in the criminal justice system that Hicks fears. From July 2018 through June 2019, according to the report, black juveniles comprised the vast majority of youths waived to adult court at 70%, while 19% were white.

“Twelve- and 13-year-olds are still children,” Hicks said, referring to SB 279. “No matter what they do, they are still chronologically young. We do not need to put 12- and 13-year-olds in a place with hardened criminals.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.