Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA plan to build the country’s first direct coal-hydrogenation refinery in southern Indiana has spawned a crop of flimsy yard signs proclaiming either support for or opposition to the project and has caused a legal argument to flourish over how much ordinary Hoosiers need to do to get their day in court.

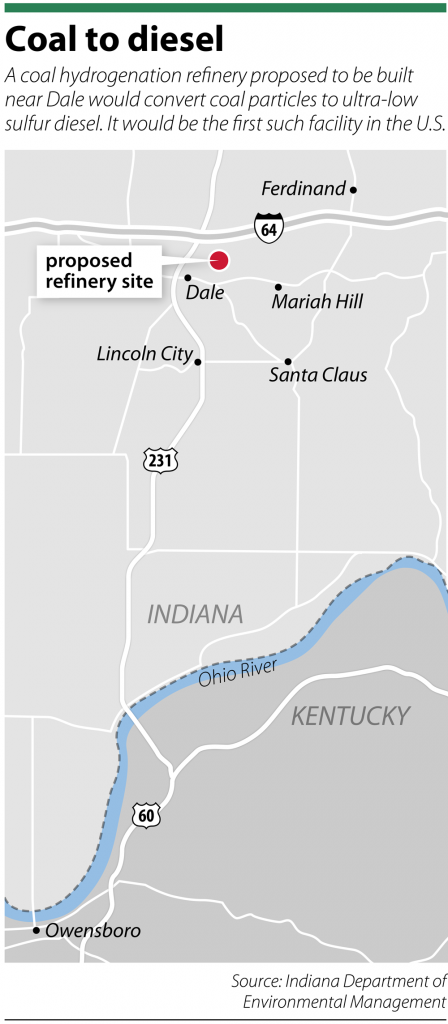

The $2.5 billion facility planned by Riverview Energy Corp. will sit on 550 acres of farmland annexed in 2017 by the town of Dale, population 1,480. It will transform coal particles into ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel through a process that uses high pressure and intense heat, according to the application for an air quality permit submitted to the Indiana Department of Environmental Management in 2018.

In press releases and in public presentations, Riverview Energy President Greg Merle has highlighted the many uses for the fuel his plant will produce and the process which, he said, has a “significantly lower carbon footprint than other technologies.” Annually the operation is estimated to produce 4.8 million barrels of diesel fuel and 2.5 million barrels of naphtha.

Also, Merle has promoted the economic boost to the local economy that will come from the 225 “permanent high-skilled, good-paying” jobs. Merle did not respond to an IL

Also, Merle has promoted the economic boost to the local economy that will come from the 225 “permanent high-skilled, good-paying” jobs. Merle did not respond to an IL

interview request.

However, a swath of residents in Spencer County have concerns. They are skeptical of the coal hydrogenation process and maintain the facility will pose a hazard to their health and the rural landscape.

Riverview Energy and the concerned residents who are part of the grassroots environmental organizations, Southwestern Indiana Citizens for Quality of Life and Valley Watch, collided when IDEM approved the company’s air permit in June 2019. This allowed the company to begin building the new facility.

The nonprofits immediately filed a petition for review in July 2019 with the Indiana Office of Environmental Adjudication to try to block the permit.

In August 2020, the OEA held an evidentiary hearing. The parties had expert witnesses testify and introduced documentary evidence. Moreover, in September, the environmental groups, Riverview and IDEM each filed post-hearing briefs and proposals for findings and conclusions.

The OEA denied the petition in December 2020, ruling that the citizens failed to uphold their burden of proof by showing IDEM did not follow the law in issuing the permit.

Riverview hailed the win.

“We are pleased with the court’s decision, of course, and had full confidence in the regulatory diligence that the Indiana Department of Environmental Management applied in vetting and issuing our air permit,” Merle said in a press release.

Southwestern Indiana Citizens president Mary Hess pointed out to Inside Indiana Business the acknowledgment by the OEA that the “cancer risk from this project exceeds the level of concern set by” IDEM. Then after questioning whether Riverview has the commitment and resources to move forward with the project, she concluded, “Ultimately, we are confident this project will never be built.”

Evidentiary standard

A close reading of the administrative judge’s final order and an analysis of the data on the OEA’s website gave the community groups grounds to challenge the denial in Marion Superior Court. More broadly, the reading and analysis has caused environmental lawyers to wonder how open the doors of the administrative courts are to the public.

“(Citizens’) voices are equally important, but they are certainly not equally represented in the decision-making process,” said Kim Ferraro, senior staff attorney with the Hoosier Environmental Council, which filed an amicus brief in support of the community groups. “They’re already at a disadvantage, and then you’ve got the OEA, which is supposed to be the one place where citizens can go to get fair review (but) in this case if the decision stands it kind of closes the door to any sort of meaningful review of IDEM decisions.”

In its response brief, Riverview, represented by Ice Miller, countered the organizations’ contentions. The company asserted the groups were making a “last-ditch effort to delay construction of Riverview’s coal hydrogenation facility” and they “misstated the law and misrepresented” the OEA’s final order.

Oral arguments in Southwestern Indiana Citizens for Quality of Life, Inc. and Valley Watch, Inc., v. Indiana Office of Environmental Adjudication, Indiana Department of Environmental Management and Riverview Energy Corporation, 49D13-2101-PL-001599, were scheduled for Aug. 30.

The petitioners are asking the trial court to reverse the OEA’s final order and remand with instructions to apply the “burden of proof in a manner consistent with Indiana law.” They are represented by Katz Korin Cunningham and Earthjustice, a nonprofit public interest environmental law firm.

Central to their petition is what they argue were the shifting standards of evidence that the administrative law judge applied. According to the groups’ petition for judicial review, the OEA decision “inconsistently applied the burden of proof in Petitioners’ case by applying different legal standards to the evidence. … Throughout the decision, the court refers to ‘substantial evidence,’ ‘a preponderance of evidence,’ ‘persuasive,’ evidence, ‘credible’ evidence, ‘adequate’ evidence, and evidence that errors ‘rise to a level that would require a remand’ … .”

The grassroots organizations hold that substantial evidence is the standard that should have been applied. In their brief to the court, the groups assert the OEA has interpreted the “substantial and reliable” language in the Administrative Orders and Procedures Act to mean petitioners must prove their cases by substantial evidence.

Also, they cite Indiana Supreme Court precedent, which has found substantial evidence has a low threshold, satisfying the evidentiary standard “when it is more than a scintilla.”

The organizations describe the OEA’s interpretation of the substantial evidence standard as “wholly unachievable for members of the public” and “inconsistent with Indiana law.”

Riverview disputes their reading of the statute. The company contends the administrative act does not establish a burden of proof for OEA petitioners.

“Nothing in AOPA states that OEA petitioners may prevail by merely submitting ‘substantial evidence’ or a ‘scintilla of evidence’ in support of their claim, and Petitioners cite no case law to that effect,” Riverview argues in its brief. “Such a rule would require OEA to disregard all evidence tendered by respondents and ignore its role to weigh the evidence and evaluate the credibility of witnesses.”

Broader perspective

The community groups have told the trial court their situation is not unique.

They pointed to data compiled by Earthjustice, which reviewed 102 final orders issued between 2010 and 2020 that are available on the OEA’s website. During that period, petitioners won just 4% of the cases they filed while IDEM was successful in 100% of the cases in which it bore the burden of proof

Ferraro said a consistent standard will not guarantee the public wins in every OEA review, but it would help by establishing a fixed target.

“It may mean that the petitioners still lose but at least … you can do that risk-benefits analysis about whether or not a case is worth pursuing,” she said. “Right now, we have no way to make that analysis because there’s no consistent standard.”

Although Spencer County might not become the home to a coal hydrogenation refinery, such a facility may break ground somewhere as the United States seeks ways to soften its environmental impact.

The research underlying the technology, according to Jay Gore, professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University, is “solid, verified and scientifically correct.” Getting support will have to happen outside the courts and instead likely hinge, he said, on “exergy,” which looks at energy production from a broader perspective that includes economic, health, environmental and political ramifications.

Working with utility companies, Gore said he is seeing the concept of “exergy” gain a foothold. Younger energy engineers who are sitting at the control stations and interacting with the operators have a different approach of wanting to provide power but in a manner that helps the environment and economy of

the towns.

Still, moving forward with new projects will require outreach. Gore advised the developers of any new energy facility to look at the geography and do studies to ensure the technology is suitable for the location. In addition, the technical, design and business teams should all be collaborating.

“It’s important,” Gore said, “for us to verify and to ensure that we have community support and we have customer support, and we are responsible members of the community.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.