Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIt’s a financial problem savvy consumers try to avoid: getting billed for out-of-network health care services.

You do your research and know the hospital where your surgery is scheduled is in your insurance network. But then you learn the anesthesiologist who treated you during surgery was not in your network.

Or, maybe you have a sudden emergency and receive treatment from a provider who’s not in your network.

Either way, you receive a bill that’s significantly more than expected.

This surprise billing — also called balanced billing — happens to about 20% of Americans, research shows. Federal and state lawmakers are working to end this practice, and leaders in both parties made surprise-billing legislation a top priority in the 2020 Indiana General Assembly.

Legislators are also working to increase transparency in health care costs to try to lower costs. A 2019 study from the RAND Corporation found that the price for inpatient and outpatient hospital care in Indiana was 311% of Medicare.

One solution is an all payer claims database that would provide patients with information about the costs of different services at different health care facilities. Nationwide, 26 states have created APCDs.

The idea of increasing health care affordability and cost transparency has received bipartisan support, but the devil has been in the details. Even so, federal lawmakers feel confident Congress will enact legislation to end surprise billing this year, while Indiana lawmakers say they’re committed to creating state solutions to drive down Hoosier health care costs.

Capping costs

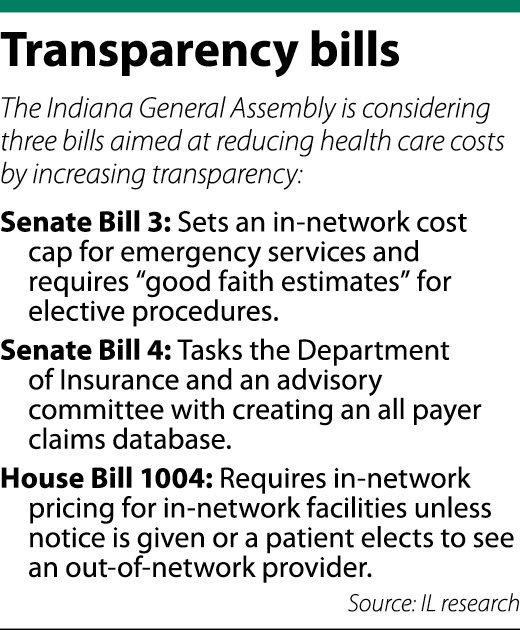

Three bills in the Indiana Statehouse are aimed at health care prices, with Senate Bill 3 and House Bill 1004 addressing surprise billing.

Three bills in the Indiana Statehouse are aimed at health care prices, with Senate Bill 3 and House Bill 1004 addressing surprise billing.

Hours-long committee meetings have featured dozens of stakeholders providing different perspectives on how to end surprise billing. The consensus is patients should be removed from the middle of cost disputes. If a patient goes to an in-network hospital but does not know a provider is out-of-network, the patient should only pay the in-network cost, leaving the provider and insurance company to determine how to make up the difference.

Senate Bill 3, authored by Valparaiso Republican Sen. Ed Charbonneau, provides that patients who see an out-of-network provider for emergency situations cannot be billed an amount exceeding their in-network costs.

For non-emergency situations, hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers or birthing centers must, at a patient’s request, provide a good faith estimate of the cost of services — including a range of costs for out-of-network providers — within five business days of a scheduled procedure. Practitioners likewise would be required to provide good faith estimates at the request of a patient.

House Bill 1004, brought by Rep. Ben Smaltz, R-Auburn, likewise caps patient costs at in-network rates for services performed at in-network facilities. A higher cost may be charged if the patient is provided notice and a good faith estimate within five days of a service.

Additionally, patients who agree in writing to paying out-of-network costs may be charged a greater amount. But if the patient does not consent and is charged an amount higher than the estimate, HB 1004 requires a written explanation.

Striking a balance

Attorneys who work in the health care industry see an important distinction between surprise billing in emergency situations versus a patient’s choice to see an out-of-network provider.

If a patient knowingly sees an out-of-network provider who is closer or more trusted, for example, they have a contractual right to make that decision, said Mike Greer, an attorney with Hall Render Killian Heath & Lyman. But if a patient is facing an emergency, just about everyone agrees out-of-network costs shouldn’t be billed.

Laura Seng, a partner in the South Bend office of Barnes & Thornburg, questioned how an “emergency” medical situation might be defined.

“Some patients use the emergency room as their primary care provider,” Seng said. “They don’t necessarily seek out primary health care — they wait until they have the flu or another illness and come into the ER department.

“That’s going to be an interesting piece to this,” Seng continued. “If a patient made a choice not to use a primary care provider but uses the ER, is that the type of emergency service that we’re trying to make sure gets no surprise billing?”

Senate Bill 3 defines emergency, while HB 1004 does not.

Seng represents hospitals while Greer represents providers, and both raised concerns about surprise-billing legislation unfairly lowering provider reimbursement. The main issue Greer and Seng pointed to is the idea of “rate-setting” in a way that takes away providers’ ability to contract with insurance companies.

“If the payer gets to set the rate, then the payer doesn’t have an incentive moving forward to negotiate,” Greer said.

Federal legislation

Republican Congressman Larry Bucshon, a cardiologist representing Indiana’s District 8, likewise is seeking a balanced approach to ending surprise billing.

Much like the state legislation, Bucshon’s plan would not charge out-of-network rates for emergency or elective surgeries performed at in-network facilities. But the key to Bucshon’s proposal is the ability of providers and insurers to negotiate the difference between in-network and out-of-network costs.

Bucshon is in favor of an independent dispute resolution process that takes the parties to arbitration. An “interim payment” should be made to the provider, he said, while arbitration works out the remaining amount.

The need for a backend dispute resolution has also come up in the Statehouse discussions. Rep. Terri Austin, D-Anderson, called HB 1004 “half a loaf” because it did not contemplate dispute resolution, though she still supported the bill. The American Hospital Association supports arbitration, Greer said.

Another key feature of Bucshon’s proposal is encouraging providers to go in-network and eliminating incentives for staying out-of-network.

Though there is bipartisan support for surprise-billing legislation, Bucshon said there are still details of his plan being worked out. Even so, he’s confident the legislation will pass in 2020, likely by May.

Whatever federal legislation is enacted would not preempt state laws addressing surprise billing, the Congressman said, a message he said he’s shared with state lawmakers.

“I want them to do what Indiana thinks works for Indiana,” he said.

The database

The creation of an all payer claims database is addressed through Senate Bill 4, also authored by Sen. Charbonneau.

SB 4 creates an advisory committee tasked with developing strategies for collecting data on health care quality, cost and other factors. The committee would work with the Indiana Department of Insurance to develop a plan to create and maintain the database.

APCDs are touted as increasing transparency, but Greer noted the database is only as helpful as its data. Those covered under the Employee Retirement Security Income Act, or ERISA, cannot be compelled to provide data, he said, so it might be limited to government payers or fully insured products.

Further, the creation of a database could place a significant administrative burden on hospitals by requiring them to provide all-inclusive estimates, Seng said. Many providers in a hospital are independent entities, she said, giving hospitals no control over their prices.

Seng also raised a concern about databases creating a price war that could push some providers out of the market. Patients might look to the database to find the lowest cost for their service without considering quality.

“It’s not the same as buying a pair of blue jeans,” she said. “… It raises concerns that people will shop based on prices and not shop based on quality of care.”

After passing their original chambers, SB 3 was referred to the House Insurance Committee, SB 4 was referred to the House Public Health Committee and HB 1004 was referred to the Senate Health and Provider Services Committee.

As of IL deadline, none of those committees had yet assigned a hearing date to the three bills.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.