Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAs 2019 draws to a close, judicial officials across Indiana are preparing for a change coming Jan. 1. On that day, Criminal Rule 26, which dictates new pretrial release protocols, will be effective statewide.

So far, 10 counties have been testing CR 26’s pretrial release rules through a pilot program, which gave officials autonomy to develop a pretrial release system that fits county culture. But the pilot counties were given parameters to work within: under CR 26, low-risk offenders should be released without bail, and courts should use evidence-based risk assessment to determine which offenders are eligible for release.

James Worton, judge of Bartholomew Superior Court 1, acknowledged there has been some resistance within the judiciary to the idea of moving away from bail. But Worton, whose county has one of the pilot programs, said the results he’s seen make him a believer in the evidence-based system.

Judicial officials in several pilot counties agree with Worton: evidence-based assessments have proven useful in making better pretrial release decisions. But even with support for pretrial reform, officials in pilot and nonpilot counties note that issues with funding and personnel are barriers to the full development of pretrial release programs.

Pilot outcomes

Across the state, 11 counties — Allen, Bartholomew, Grant, Hamilton, Hendricks, Jefferson, Monroe, Porter, St. Joseph, Starke and Tipton — have been developing pretrial release programs under the pilot program. Marion County has also revamped its bond matrix in light of CR 26, though the Indianapolis courts are not part of the official pilot.

In Bartholomew County, assistant chief probation officer Kim Maus said the Columbus-based courts were reviewing their pretrial practices before CR 26 came on the radar. Jail overcrowding is an issue in Bartholomew County, Maus said, so county officials began looking to evidence-based assessment as a means of easing the jail’s burden.

From Worton’s perspective, pretrial assessments have been a helpful tool in determining whether a defendant is a flight risk or is likely to commit a new crime if they are released after an initial hearing, the two main factors considered under CR 26. Probation officers conduct the assessments during face-to-face meetings with defendants, and prosecutors have the opportunity during the hearing to inform the judge if they believe a defendant was dishonest in the assessment, he said.

Similarly in St. Joseph County, judges retain discretion over pretrial release decisions even when presented with an assessment, Kate Williams and Jesse Carlton said. As the executive administrator of St. Joseph County Community Corrections and chief probation officer, respectively, Williams and Carlton were part of the comprehensive review and overhaul of the northern Indiana county’s pretrial release and bond system.

As is customary, before the CR 26 pilot, St. Joseph County used a presumptive bond schedule based on the level of a charged offense, Williams and Carlton said. But under the pilot program, defendants are now assessed for pretrial release using statewide practices and locally developed factors, including whether a defendant has a history of domestic violence, crimes involving weapons or crimes against law enforcement officers.

Under the CR 26 pilot, St. Joseph County has completed 3,079 pretrial risk assessments since October 2017 and has seen a 26% reduction in the average length of pretrial jail stays.

Assessment factors

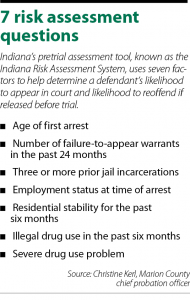

While each pilot county has put their own spin on implementing CR 26, the Indiana Risk Assessment System-Pretrial Assessment Tool is a fixture. Christine Kerl, Marion County’s chief probation officer, discussed the tool during an Aug. 27 meeting of the General Assembly’s Interim Study Committee on Corrections and Criminal Code.

While each pilot county has put their own spin on implementing CR 26, the Indiana Risk Assessment System-Pretrial Assessment Tool is a fixture. Christine Kerl, Marion County’s chief probation officer, discussed the tool during an Aug. 27 meeting of the General Assembly’s Interim Study Committee on Corrections and Criminal Code.

According to Sen. Mike Young, the Indianapolis Republican chairing the study committee, CR 26 was assigned as a review topic as part of a broader review of the impact of criminal code reform. That reform has led to increased concerns about jail overcrowding, Young said, and CR 26 was seen as a way to help resolve that issue.

According to Sen. Mike Young, the Indianapolis Republican chairing the study committee, CR 26 was assigned as a review topic as part of a broader review of the impact of criminal code reform. That reform has led to increased concerns about jail overcrowding, Young said, and CR 26 was seen as a way to help resolve that issue.

The IRAS-PAT assessment consists of seven factors. The first six factors — failures to appear, prior incarcerations, employment and residential status, drug use and age of first arrest — are self-reports, Kerl told Indiana Lawyer. But the seventh factor, the existence of a severe drug use problem, also involves an officer’s assessment.

Speaking to the study committee, Kerl said the 1,892 pretrial assessments conducted in Marion County since July 2017 have identified 9% of defendants as low risk, 48% as moderate risk and 43% as high risk. Also among the 1,892 assessments, only 33% of defendants were terminated from pretrial supervision for new felony offenses, technical violations or failures to appear.

Currently in Marion County, defendants who are being held pending an initial hearing are assessed, Kerl said. But the goal is to eventually assess all defendants being held in the Marion County Jail, an idea echoed in other pilot counties.

Limited resources

Though court officials generally speak well of the CR 26 pilot, other stakeholders have raised concerns.

For example, Bernice Corley, executive director of the Indiana Public Defender Council, asked during the Aug. 27 meeting whether the assessment tools have been screened for bias. Data is still being collected on that issue, but officials have said they are actively looking to avoid bias.

On the prosecution side, departing Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council executive director Dave Powell — who, like Corley, sits on the study committee — cautioned committee members against believing pretrial reform would solve all jail overcrowding issues. Similarly, Worton said the pilot program has helped, but has not eliminated, jail overcrowding in Bartholomew County.

Also testifying before the committee was Lena Hackett, founder and president of Community Solutions, an organization that engages in criminal justice reform work, among other initiatives. While larger counties such as Marion might have the resources to dedicate to pretrial release reform, Hackett said smaller counties might not.

Indeed, Jay Superior Judge Max Ludy told Indiana Lawyer he is not yet sure what pretrial reform will look like in his court. Right now, he uses a system where he assesses overnight arrestees via video about 6 or 7 a.m. each day to determine if they are eligible for release. Ludy doesn’t use a point system like what’s in the IRAS-PAT, but he does evaluate defendants using similar factors.

The problem, Ludy said, is that there is not enough money to hire the local staff needed for pretrial release reform. The county has only a handful of probation officers, he said, and none can be spared to fully dedicate their time to pretrial assessments.

Further study

Mary Kay Hudson, executive director of the Indiana Office of Court Services, says the judiciary is aware of the funding problem. The state has provided grant funding, as well as training, to the pilot counties, but Hudson said further discussions with the General Assembly and state agencies are necessary to determine how the state can best support the implementation of CR 26 in all 92 counties.

Those conversations will be the focus of an Oct. 4 pretrial summit, Hudson said. Stakeholders from all counties, including legislative stakeholders, have been invited to come together and discuss the successes and failures of the pilot program.

The idea of the summit, Hudson said, is to discuss pretrial best practices, help pilot counties determine their next steps and assist counties such as Jay in taking the first steps toward implementing pretrial reform efforts.

Ludy said Jay County plans to send a team to the summit to hopefully take home some tips. Several lawmakers on the study committee likewise said they plan to attend.

A mindset shift will also be needed to make pretrial reform work, Maus said. People feel comforted by the idea of money bail, she said, and it will take time to change that.

What’s more, Worton noted the Indiana Constitution includes a right to bail, so it would take a major legislative change to fully move away from a money-based system.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.