Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Flat-footed.

That’s how Indiana Chief Justice Loretta Rush describes the judicial response to the opioid crisis.

“We should have set up an addictions framework back during the crack cocaine epidemic,” Rush said. “Shame on us.”

During her days on the Tippecanoe County trial bench, which she left in 2012, Rush was seeing evidence of the opioid crisis manifest itself through babies born with neonatal abstinence syndrome. As the drug problem has grown, courts have increasingly struggled to keep up with rising numbers of drug-related cases ranging from criminal matters to child welfare to housing and more.

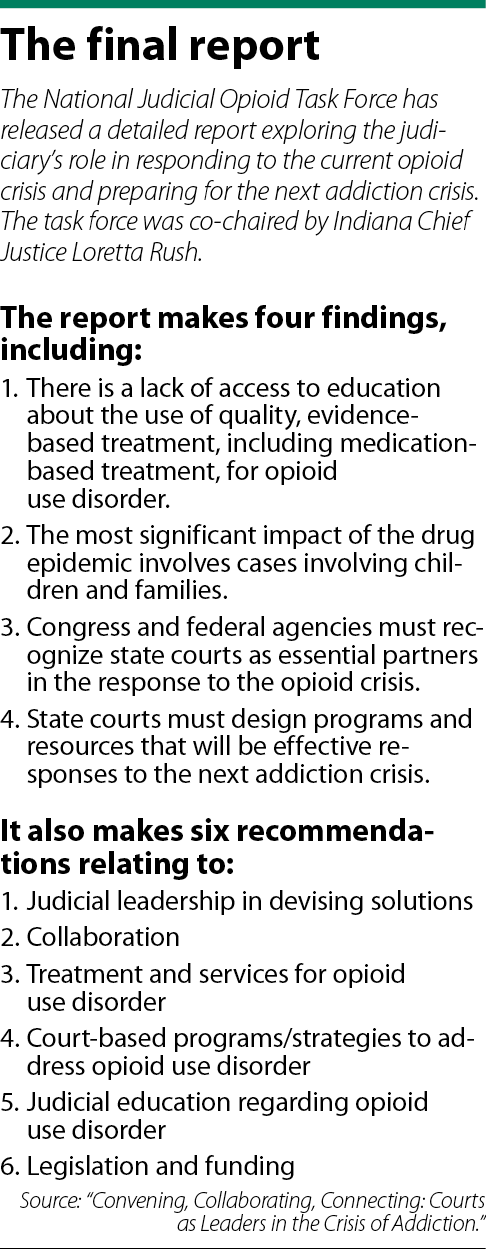

In response, the National Judicial Opioid Task Force was created in 2017 to delve into ways the judiciary could get a handle on the opioid crisis. Co-chaired by Rush and Deborah Tate, director of the Tennessee Administrative Office of the Courts, the task force’s work culminated late last month in the release of a report that includes four findings and six recommendations for how courts can respond to the current drug scourge and be better prepared for the next addiction crisis.

The task force released bench cards and other tools designed to assist judges as they learn to use evidence-based methods when dealing with defendants who have an addiction. The next steps will involve education and training to ensure judges and other members of the criminal justice system understand how treatment and rehabilitation can keep drug offenders out of the system.

Community conveners

Community conveners

An overarching theme of the Nov. 20 report is the idea of courts as “conveners” of community stakeholders who play a role in responding to addictions. The recommendations are built on the notion that all community stakeholders – courts, law enforcement, treatment providers, etc. – must play a role in responding to addictions, and judges are uniquely positioned to bring them all together.

“In short,” the report says, “when a judge convenes a community meeting to deal with a social issue affecting their community, people show up.”

Brandon George, executive director of the Indiana Addiction Issues Coalition, gave the example of the 2018 Statewide Opioid Summit, which brought together judges and other representatives from across the state. George, who served as an adviser to the task force, said the expectation was that about 55 counties would be represented.

“All 92 showed up,” George said. “People respond to judges.”

Judges aren’t doctors, Rush pointed out, so their need to work with the community is vital. After all, judges order services for addictions from the bench, so they need to understand the science of addiction.

To that end, the toolkit includes resources designed to help judges, lawyers and other advocates within the system gauge what treatments or services might work best for each individual. Both Rush and George highlighted the importance of lawyers as the ones who can teach judges and advocate on behalf of clients with addictions.

Local efforts

Even before the task force report, courts have been implementing initiatives tailored to the drug crisis. In Indiana, one such initiative is problem-solving courts, where defendants with both criminal and civil troubles can receive specialized attention from a judge.

Hancock Circuit Judge Scott Sirk presides over an Adult Drug Court, where successes are celebrated and failures are punished, though even the punishments have an eye toward rehabilitation.

For example, one participant recently relapsed, Sirk said, but she told the court about it immediately. Though they have to address her relapse, the judge said the woman’s honesty is still a success.

Hancock County also has a specialized “heroin protocol,” which is run by Amy Ikerd. In that program, defendants with a heroin addiction are sent to a recovery house, where they are supervised for 90 days. The idea of the program, Ikerd said, is to assist defendants who otherwise might go back to drugs as soon as they are placed on probation.

In Bartholomew County, Judge Heather Mollo oversees the Family Recovery Court, which serves parents who have addictions that have led to children in need of services filings. The program is aimed at maintaining family stability, with representatives from the Department of Child Services and the Court Appointed Special Advocates program, among others, regularly involved in the proceedings.

Mollo recalled a recent case in which a young mother was addicted to methamphetamine and was seeking treatment for the first time. The mother didn’t know where to start, but the advocates were able to find a bed in a recovery home that would take her immediately and allow the mother to keep her baby.

“That’s the beauty of it – that’s how quickly we can make adjustments to treatment,” Mollo said.

Grant Superior Judge Jeff Todd presides over the Re-entry Court, which is a condition of probation for most Grant County cases. A majority of participants will have a positive drug screen on their first day of Re-entry Court, Todd said, because they are using while in the Department of Correction.

Data shows that between January 2015 and September 2019, 166 people enrolled in the Grant County Re-entry Court program. Of those, 44.8% have graduated, 42.8% were terminated from the program and 7.6% are still in the program.

Participants who have successfully completed the program are proven to be less likely to reoffend when the reenter society, Todd said. Even so, he and the other judges said their counties are still pursuing ways to increase success rates.

“Addiction is a strange creature,” Todd said. “We’re doing our best. We try everything from all evidence-based treatment, including drugs. Everything we can.”

Public health vs. safety

Conversations about the addiction crisis have always included talk of gateway drugs, but George views that conversation differently.

“Trauma is the real gateway drug,” he said. “It’s not because you tried marijuana. It’s because you’ve experienced adverse childhood trauma, or you’ve had other experiences of trauma in your life.”

Indeed, Sirk said many of the women in the Hancock County Drug Court program have suffered abuse, while Rush noted that mental illness is prevalent in the jails. The trauma that triggers addiction doesn’t have to be “severe,” George said – experiences such as losing a parent can create feelings of abandonment, which can fuel addiction.

The mental health aspect of addiction is key to George’s message: addiction is not a public safety issue, but a public health issue. Likewise, the report calls on courts to be smart on drugs, not just hard on drugs, and Rush said she’s seeing judges begin to take on that mindset.

Both Rush and George spoke of the Sequential Intercept Model, which maps points in the criminal justice system where behavioral health issues can be addressed. As judges learned about SIM, Rush said she expected them to care about later points, such as Intercept 3, which pertains to the jails/courts.

But instead, the chief said judges have been more interested in Intercepts 0 and 1, which include community services and law enforcement.

“They want to know how to prevent these people from coming to court,” she said.

Lost generation

Despite being caught flat-footed, Rush and Indiana judges say they think the courts, through their response to the opioid crisis, are beginning to make a dent in the impact of the drug scourge. Even so, the chief said the task force wanted to create recommendations that could be tailored to the next addiction crisis, regardless of what drug that might include.

Already, court officials say they’re seeing a resurgence of meth, which has long been among the top drugs in Indiana. Meth never really went away, they say – opioids such as heroin just got more attention.

Saying the crack cocaine epidemic was “terribly handled,” George said he’s pleased the task force report focuses on more than just opioids. From Rush’s perspective, the future-focus is about saving lives.

“We’re losing a generation,” she said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.