Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIt’s no secret jury trials are declining across America, even as they are increasing in other parts of the world. What’s less obvious, though, is why that decline is occurring.

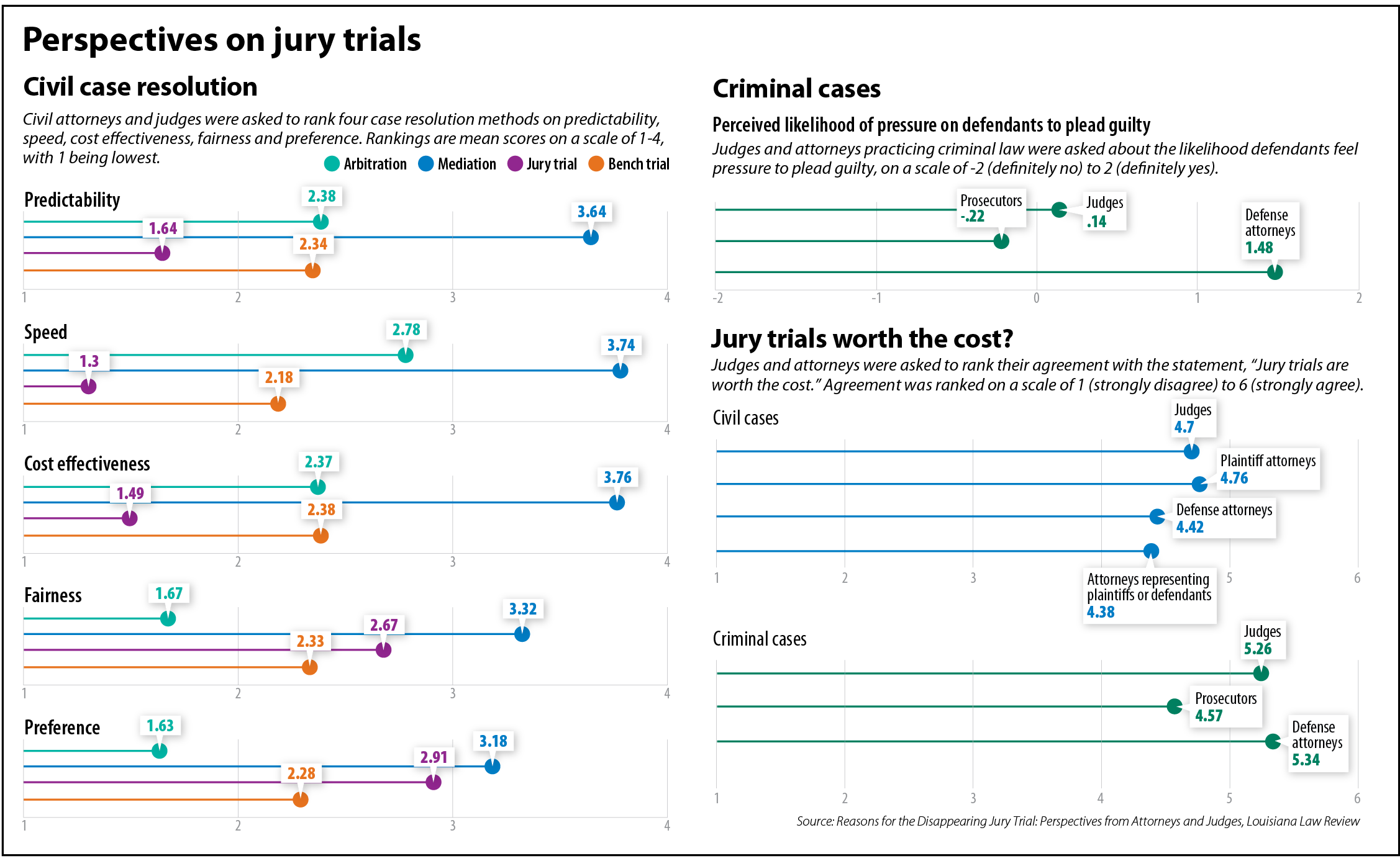

A recent study co-authored by a research professor with the American Bar Foundation, “Reasons for the Disappearing Jury Trial: Perspectives from Attorneys and Judges,” interviewed 1,460 American lawyers and judges on the merits of mediation, arbitration, jury trials and bench trials to determine why some case resolutions are more common than others. The results found that while most legal professionals think jury trials are fair, factors such as time, cost and external pressures can lead litigants and defendants to plea agreements and settlements.

Indiana legal professionals say the issue is complex. Juries are generally fair and accurate, lawyers say, but alternative dispute resolution also has merit. The proper resolution is usually case-specific, they say.

“We were watching the rates of jury trials go down and down and down, and we were concerned about that,” said Shari Seidman Diamond, the study’s co-author. Diamond is a professor at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law and conducted the study with Jessica Salerno of Arizona State University.

“The jury is an important part of the American legal system in terms of offering services to potential litigants and criminal defendants and citizens generally,” Diamond said.

Civil decline

The study, published in the fall 2020 edition of the Louisiana Law Review, identified four main factors for the decline in jury trials. On the civil side, the study pointed to damages caps and mandatory arbitration, while criminal factors included the sentencing guidelines and mandatory minimum sentences.

Dennis Stolle, a partner at Barnes & Thornburg and president and founder of jury consulting firm ThemeVision LLC, noted that jury trials remain relevant. He pointed to data from the National Center for State Courts that estimated some 10 million Americans were called for jury duty each year before the pandemic.

“Sometimes the headlines can be misleading, and people can walk away thinking there are no more jury trials, which is not accurate,” Stolle said. “It’s more like there’s not that many relative to the astounding number of lawsuits that get filed.”

In Indiana, jury trials in 2019 accounted for 0.09% of all case dispositions — 1,142 cases out of 1.3 million dispositions total, according to data from the Indiana Supreme Court.

Fred Schultz, a plaintiffs’ personal injury lawyer and president of the Indiana Trial Lawyers Association, agreed with the study that damages caps and mandatory arbitration are major factors in civil cases settling. Schultz pointed to the $300,000 cap on damages for the wrongful death of an adult without dependents, saying it is “tragically easy” to calculate the value of such a case.

Louis Voelker, a medical malpractice defense lawyer in Hammond, agreed that in some instances, damages exceed the cap. But Voelker added that the cap is meant to establish “a fair and effective system for an entire body of cases,” rather than looking at cases on the individual level.

Voelker attributed the rise in alternative dispute resolutions generally as one of the main reasons for the decline in jury trials. Mediation has become so common in his work that court bailiffs will ask parties pretrial whether they’ve been to mediation.

As a result, Voelker said, mediation has become a more informed process, often occurring later in the case. The study found generally favorable views on mediation, with judges and lawyers ranking it highest in terms of predictability, speed, cost, fairness and general preference.

Arbitration earned high marks for speed and predictability but low marks for fairness and preference. Schultz opined that arbitration is often “forced” on parties through arbitration clauses, which is why the process is commonly used but not always preferred.

Criminal factors

Jim Oliver, a former Brown County prosecutor and current deputy director for criminal law at the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council, was surprised at the data showing a decrease in jury trials. In his work, he speaks with prosecutors almost daily who are preparing for, in the middle of or wrapping up a trial.

Even so, the numbers show a decline, and Oliver theorized that the rise of felony diversion programs across Indiana could be a cause. He also pointed to the increase in digital evidence such as cellphone evidence and emails that can make a prosecution stronger.

Michael Moore, assistant executive director of the Indiana Public Defender Council, agreed that digital evidence can make it more difficult to defend a case.

Moore pointed to drug cases, which previously were tried with evidence from a wire worn under someone’s clothes. The quality of that audio was not always strong, Moore said, but with today’s technology, including better cameras, it has become more difficult to dispute digital evidence. In those situations, Moore said, the defense fight often focuses more on sentencing.

Where mandatory minimums are in place, Moore said there is an incentive to plead guilty to a lesser charge that avoided those minimums.

Also, enhancements and credit restrictions can increase a defendant’s potential jail time, Moore added. That can incentivize a guilty plea, especially if the state’s case is strong.

The study also found a belief among lawyers, particularly defense lawyers, that defendants are often “pressured” to plead guilty, and Moore agreed that pressure from the bench, bar and even family is common.

Oliver, however, noted that “pressure” is not always negative.

“If a defense attorney goes to a client and says, ‘You’re going to be convicted so I encourage you to plead guilty,’ that might be pressure, but it’s perfectly appropriate pressure. It’s good advice kind of pressure,” the former prosecutor said.

Reversing the trend

Speaking with Indiana Lawyer, Diamond called for abolishing mandatory minimums and reevaluating the federal sentencing guidelines, which she said have “ratcheted up” the potential sentences criminal defendants face.

On the civil side, Diamond said she would jettison mandatory arbitration and, at a minimum, increase damages caps.

Voelker noted the damages cap for Indiana medical malpractice cases has been raised twice in recent years, and he doesn’t necessarily think eliminating those caps would lead to more jury trials.

But Voelker added that he would like to try more cases before a jury, noting that he uses his jury experience as a reference point even when his cases go to mediation.

“When you go to a mediation one of the things you’re doing is analyzing where a jury is going to come out on this case, and how does that drive each of our settlement positions?” he said.

Stolle pointed to what he said is a rarely used tool available to Indiana practitioners: summary jury trials. Found in Rule 5 of Indiana’s Rules for Alternative Dispute Resolution, summary jury trials are streamlined proceedings that are not binding on the parties.

Stolle advocated for the increased use of summary jury trials, which he described as the “best of both worlds” between a traditional trial and ADR.

“It’s more like a procedure to inform the parties and to help settle the case,” he explained. “It’s a really streamlined procedure … but it allows the parties the chance to go through the useful process of bringing people in off the street to tell you what they think.”

Hamilton Superior Judge David Najjar opined that the best option might be a middle ground approach. Litigants and defendants should never feel pressured to forgo a jury, he said, but they should be made aware of alternative options.

Najjar pointed to the practical reality that judges often order mediation simply from a numbers perspective.

“If every case went to a jury trial, that would be a lot more judicial resources, a lot more judges, a lot more courtrooms. Juries aren’t cheap,” Najjar said.

“… To the extent that we want to encourage jury trials, I’m not sure that we go that far in that direction,” the judge said. “But I think to provide that as an alternative with some of the other things is where we ought to be going.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.