Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

The fallout from the revelation that the former Park Tudor boys basketball coach exchanged explicit messages with a 15-year-old student continued last week, when the school’s former attorney was subject to a disciplinary hearing over his conduct during the school’s investigation.

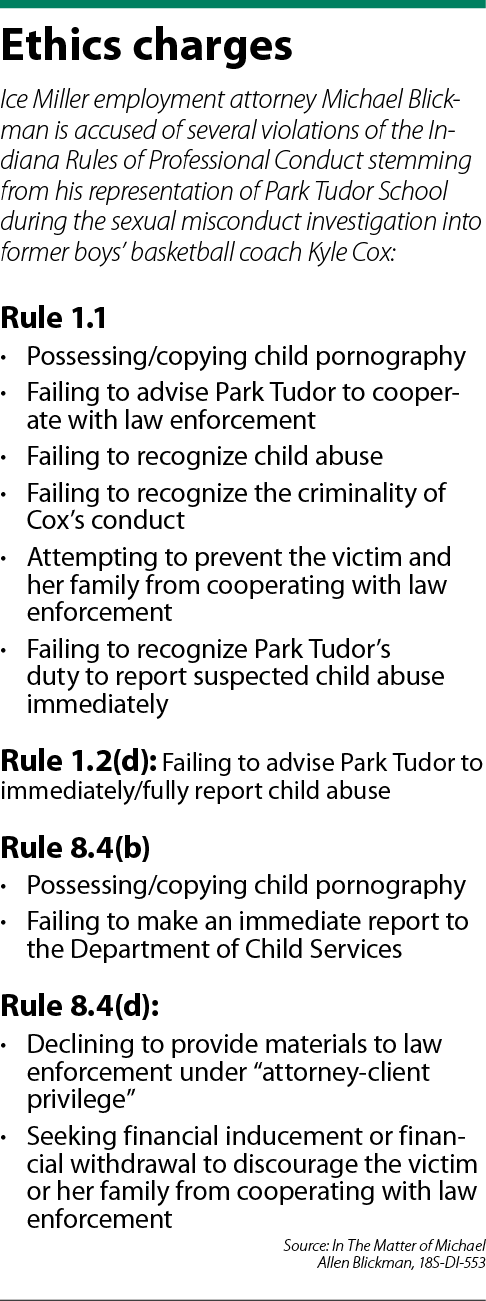

Ice Miller partner Michael Blickman appeared before hearing officer and Elkhart Senior Judge Terry Shewmaker Sept. 23-26 for the hearing in In the Matter of Michael A. Blickman, 18S-DI-553. Blickman, a prominent employment attorney, has been accused by the Indiana Supreme Court Disciplinary Commission of unlawfully copying and possessing child pornography and of trying to interfere with the criminal investigation into former coach Kyle Cox.

There’s little dispute about the core facts surrounding Cox’s illegal conduct. But what is in dispute are Blickman’s knowledge and motivations during the subsequent investigation, conducted while he represented the school in employment law issues.

Shewmaker’s report and the disciplinary ruling by the Indiana Supreme Court could shed light on important lawyer ethical questions, including questions about when lawyers are required to report suspected child abuse and the extent to which attorney-client privilege can be applied.

The facts

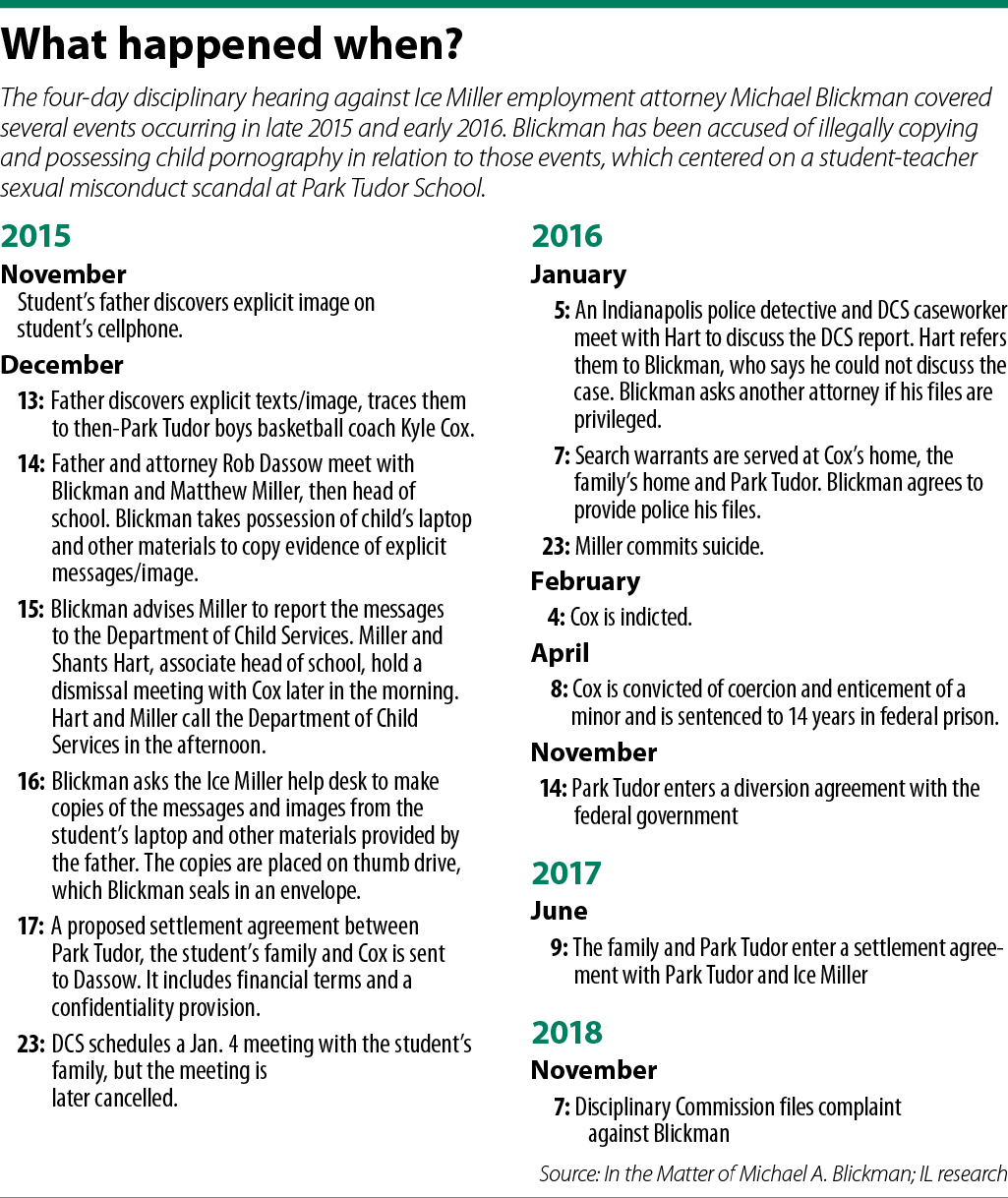

Blickman’s disciplinary action, filed in November 2018, traces back three years earlier, when the student’s father discovered an image of male genitalia in his daughter’s text messages. Subsequent investigation into messages and a video found in December 2015 led the father to the conclusion that Cox was the person his daughter was texting.

The father, along with his attorney, Rob Dassow, called a meeting with Park Tudor headmaster Matthew Miller on Dec. 14, and Miller asked Blickman to join. It was then that the father presented Miller and Blickman with printouts of the messages and images, as well as his daughter’s laptop.

Cox was fired the next day during a meeting with Miller and associate head of school Shants Hart, though it was later reported that Cox had resigned. Miller and Hart filed a child abuse report to the Department of Child Services that afternoon, with Hart acting as the principal reporter.

Cox was fired the next day during a meeting with Miller and associate head of school Shants Hart, though it was later reported that Cox had resigned. Miller and Hart filed a child abuse report to the Department of Child Services that afternoon, with Hart acting as the principal reporter.

Over the next few days, drafts of a settlement agreement began to circulate among the parties. The agreement included financial incentives for the family, as well as a confidentiality provision.

Later, an Indianapolis police detective and DCS caseworker attempted to gain information about the situation from Blickman, who declined under attorney-client privilege. Instead, law enforcement executed search warrants at Park Tudor, Cox’s home and the family’s home, prompting Blickman to provide police with the information he had.

Divergent views

Differing analyses of this set of facts are the heart of the disciplinary action. In its complaint and questioning, the disciplinary commission painted a picture that showed Blickman acting only in the interest of Park Tudor, which was his client and his children’s alma mater.

Testifying under direct examination of commission attorney Seth Pruden, the student’s father admitted he gave his daughter’s laptop and printouts of the messages to Blickman but said he did not know copies of the materials would be made. And when the laptop was returned, the father said he was surprised to learn a thumb drive had been inserted and the computer’s terminal shell, where computer commands can be made, had been opened.

But Blickman, represented by a team of attorneys from Hoover Hull Turner in Indianapolis, including former Justice Ted Boehm, said he was thinking like a labor lawyer when he copied the materials. He testified that because the father had admitted to deleting at least one message between his daughter and Cox, he believed he needed to preserve the remaining messages as evidence.

Also testifying as commission witnesses were Keith Page and Preston Beamer, the two Ice Miller helpdesk employees who made copies from the student’s laptop. They described the process they went through to copy the materials, including opening the terminal shell to better understand how to copy the messages and uploading the copied materials to a thumb drive.

The father also said he was later surprised when he was presented with a settlement agreement that included a confidentiality provision, to which Cox had agreed. The family declined to sign the agreement, but both Blickman and Hart said the confidentiality provision was intended to keep Cox from spreading false information about the situation. Further, Blickman testified that both the family and the school had consistently insisted on confidentiality, and the confidentiality provision included in the agreement was standard.

Blickman also said the financial terms in the agreement had been the idea of Dassow, the family’s attorney. When Blickman presented Dassow with the agreement, he said Dassow never indicated any of the terms were inappropriate.

On the issue of possession of child pornography, Blickman said he never believed copying the materials would be an illegal act. He’s a labor attorney, and a criminal attorney whom he consulted did not advise him against copying or keeping the explicit materials. But in opening arguments, Pruden said it was not Blickman’s job to preserve evidence — that was the job of the police.

Central to the commission’s complaint was the school’s report to DCS and subsequent cooperation, or lack thereof, with the criminal investigation. A key point was the fact that during the call to DCS, Miller indicated to Hart that he did not know if the messages between Cox and the student involved images. Hart conveyed that uncertainty to DCS officials.

Witnesses said Miller’s statement was a lie, as the father had shown him the explicit images during the Dec. 14 meeting. But Blickman maintained that he believed DCS was fully informed of the situation, saying he was shocked to later learn about the omission of information.

The timeline leading to the call to DCS was also key. The call was made on the afternoon of Dec. 15, but the commission argued Blickman should have advised the school to make the call on Dec. 14 pursuant to a statute requiring “immediate” reporting. According to the complaint, Blickman had earlier the same year advised Miller to report inappropriate touching of a student by another student in an unrelated matter, but he did not advise Miller to report the matter involving Cox on the day of the meeting with the student’s father.

But in his testimony, Blickman repeatedly reiterated the family’s call for confidentiality. When Miller asked Blickman on Dec. 14 whether a public report was necessary, Blickman told the headmaster he would research the matter.

According to Blickman, he got up at 5:30 the next morning to conduct that research and had advised the school by around 7 a.m. of its requirement to call DCS. Miller said he would do so.

According to Blickman, he got up at 5:30 the next morning to conduct that research and had advised the school by around 7 a.m. of its requirement to call DCS. Miller said he would do so.

Once DCS and IMPD became involved, Hart referred Det. Laura Smith to Blickman, whom Hart said could answer IMPD’s questions about the Cox situation. Blickman initially refused, saying the attorney-client privilege prevented him from discussing the case. Smith said she was shocked by this response, and then-Marion County Prosecutor Terry Curry, whom Blickman and Dassow contacted, testified that he told the attorneys he would not call off the investigation.

Curry also testified that he did not believe such a privilege existed, and the commission has accused Blickman of using a non-existent privilege to impede the investigation. But Blickman said he conferred with a criminal attorney, who did not say definitively that his notes regarding the Cox situation were subject to law enforcement review.

But when a search warrant was executed at the school on Jan. 7, 2016, Blickman agreed to provide law enforcement with the information he had. He also said that day was the first time anyone ever suggested that his copying and possession of the messages could be criminal.

Next steps

A central issue in Blickman’s case hearkens back to a previous conversation among Indiana ethics lawyers: when are attorneys required to report child abuse in light of attorney-client privilege?

A 2015 opinion from the Indiana State Bar Association Ethics Committee said attorneys are only required to report “to prevent reasonably certain death or substantial bodily harm,” a ruling that rankled many in the child protection industry. Steve Badger, current chair of the ethics committee, said the issue of child abuse reporting has not come up again in recent years.

The hearing concluded Sept. 26, though neither side presented closing arguments. Instead, briefs containing the arguments must be submitted to Shewmaker within 60 days of the official record being prepared.

Blickman has never been the subject of a previous disciplinary action, and he testified that no previous clients have filed a grievance against him. The current case was prompted by a filing made with the commission by the Department of Justice.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.