Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA legal battle over a large hog farm in rural Hendricks County has been progressing like other previous lawsuits against concentrated animal feeding operations in Indiana: the neighbors who brought the complaint have been losing.

Susan Lannon, one of the plaintiffs, admits her nerves cannot take much more. Yet she is continuing to fight because she believes what is happening at her homestead could happen almost anywhere in the Hoosier State.

“Somebody has to do something,” she explained.

At the center of this dispute are the smells from 4/9 Livestock, which neighbors say are so strong and overpowering they can no longer enjoy their homes and properties. In court documents, Richard and Janet Himsel and Robert and Susan Lannon claim the “stench from the ammonia and other noxious compounds” burns their noses, throats and eyes and, at times, has seeped inside their homes through the closed windows and forced them to leave.

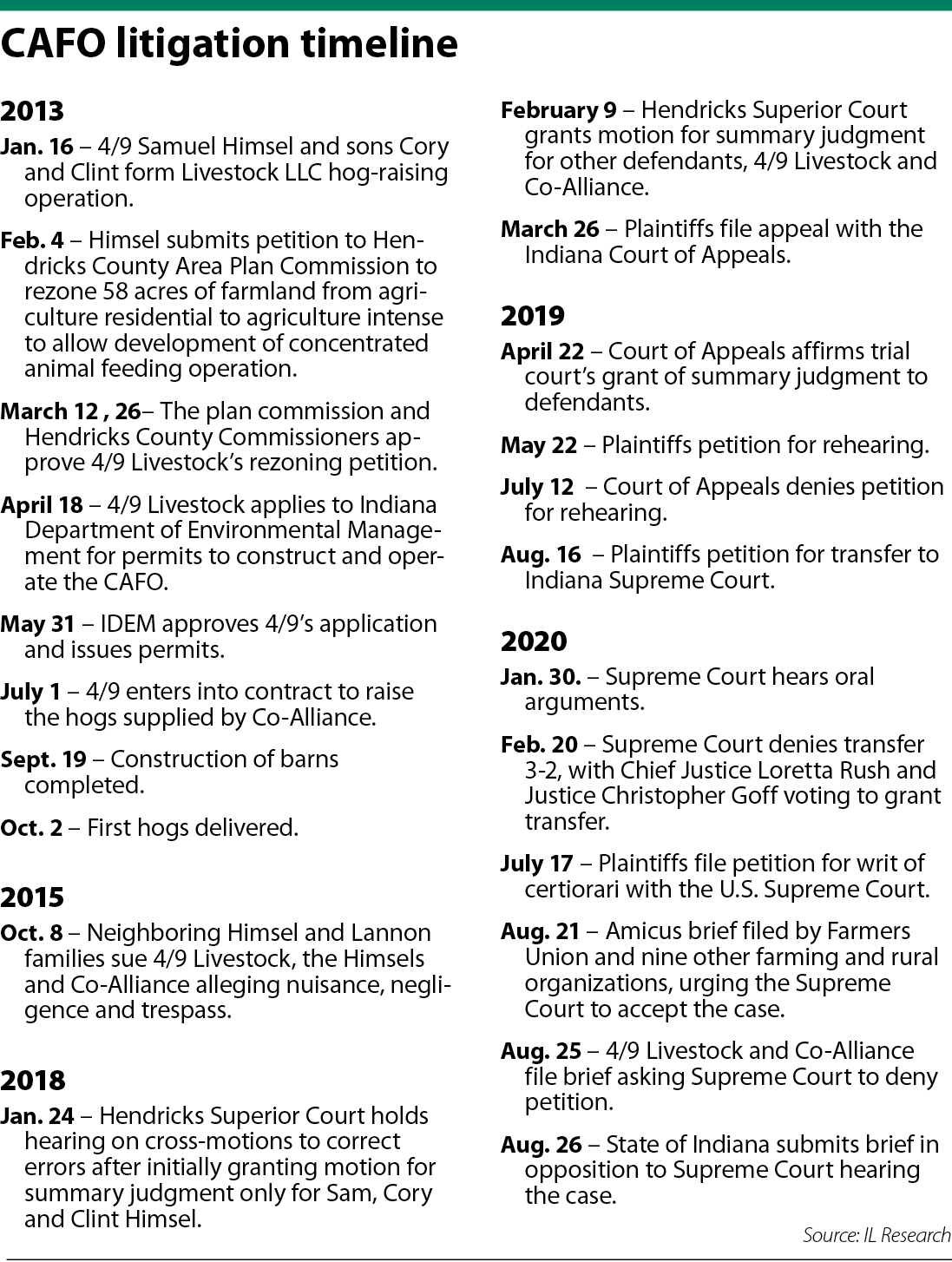

The families filed their lawsuit against 4/9 Livestock and its owners in 2015, but the Hendricks Superior Court found Indiana’s Right to Farm Act blocked their nuisance, negligence and trespass claims. They unsuccessfully sought relief from the Indiana Court of Appeals and a divided Indiana Supreme Court, so they are now turning to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In their petition for writ of certiorari, filed in July, Richard and Janet Himsel and the Lannons argue Indiana’s RTFA violates the Takings Clause of the U.S. Constitution. They are unable to get relief because the state statute provides 4/9 Livestock “complete immunity from nuisance and trespass” complaints.

However, attorney Christopher Braun counters Samuel Himsel and his sons Cory and Clint, his clients who started 4/9 Livestock, are the ones who cannot get any relief. The family has grown corn and soybeans for generations but, wanting a more stable income, they expanded their farm in 2013 to include the concentrated feeding animal operation (CAFO).

The 4/9 Livestock CAFO feeds 8,000 hogs kept in an enclosed building, according to Braun, partner at Plews Shadley Racher & Braun in Indianapolis. Co-Alliance, also a defendant in the case, supplies the piglets, the feed and the veterinary services. Twice a year after the hogs are shipped out, the Himsels will clean the barn and apply the manure that has been captured in an underground concrete bunker onto their fields.

Prior to starting their operation, the Himsel farmers went through the process to get their property rezoned by the county and properly permitted by the Indiana Department of Environmental Management, Braun said. They presented their plans at multiple public hearings, secured a seven-figure bank loan and were raising hogs for two years before their neighbors sued.

“There has to be finality in the process,” Braun said. “They do everything by the book and still get dragged into court.”

Lifestyle vs. livelihood

Like other states across the country, Indiana enacted its Right to Farm law in 1981 to protect Hoosier family farms from urban sprawl. The statute was intended to prevent nuisance lawsuits from being filed by new neighbors who, upon moving into just-completed subdivisions, found they did not like living so close to the smell, dust and sounds typical of barnyards.

In 2005, the Legislature amended the RTFA, which had stated a farm could become a nuisance if there was a “significant change” in things such as the hours, size or type of operation. The new language redefined “significant change” to exclude changes in type and size, so a farm that becomes a CAFO is exempt from nuisance claims even from longtime neighbors.

“It’s a law that unfairly strips pre-existing landowners of their ability to protect their property rights in court,” said Kim Ferraro, senior staff attorney with the Hoosier Environmental Council, who is representing the plaintiffs.

Indiana is not the only state to have revised its Right to Farm law. Proponents assert the statutes are being updated to reflect the practices of the modern farmer while opponents counter the new language is allowing big business to operate factory farms without worry.

Jessica Culpepper is an attorney and director of the Food Project for the nonprofit Public Justice based in Washington, D.C., combating social and economic injustice. She said the revamped farming laws are benefiting corporations and hurting family farms as well as rural communities.

Confining animals in large buildings creates “massive waste deposits” that can pollute the water and air, Culpepper said. Industrial operations are “completely destroying a way of life” not only by hurting family farmers’ use and enjoyment of their land but also by endangering their health and the health of their animals. Yet Right to Farm laws have taken away any recourse the traditional farmers had to protect their ability to produce food and make a living, she said.

Although Culpepper is not optimistic the Supreme Court will grant cert, she hopes Himsel sends a message.

“I hope (states) hear that passing Right to Farm laws that grant complete immunity to agricultural operations at the expense of family farms are not only wrong but against our Constitution,” she said.

Todd Janzen of Janzen Agricultural Law LLC in Indianapolis disputes that RTFA grants blanket immunity. Farmers “doing what farmers do” will have some immunity, he said. But the Indiana law states its protections do not apply “if a nuisance results from the negligent operation of an agricultural or industrial operation,” so, Janzen continued, farmers acting outside the state mandates, like applying manure without following the state chemist’s regulations, could be subject to a nuisance lawsuit.

Rather, Janzen said, Indiana’s RTFA law enables farms to remain viable by allowing them to update practices and incorporate new methods. He pointed to Obert Legacy Dairy in Gibson County, which built a CAFO housing more than 700 dairy cows, enabling the owner’s son to return home and make a living on the family’s farm.

Neighbors filed a nuisance complaint in 2011, alleging the odors from the operation devalued their property and caused personal injury. The Indiana Court of Appeals found RTFA protected the Oberts from the lawsuit because the transformation of their farm from 100 to 760 cows was not a “significant change.”

“I think it’s wrong to think farming can be stable,” Janzen said. “Farms aren’t going back to what they were 50 or 100 years ago. Farms like any industry change over time. Farms have to have the ability to expand and change the way they operate to adapt to modern times.”

A taking?

Robert Lannon has lived on his 20-acre plot in rural Hendricks County since he built his home there in the 1970s. During the summer, his wife Susan has planted vegetables and flowers from her mother’s garden, and, in the evenings, they used to open the windows to hear the serenade of crickets and frogs.

Now with the odor that comes when the wind blows from the direction of 4/9 Livestock, the Lannons say they are unable to stay outdoors and they cannot have family and friends visit. In addition to the health issues they say they are suffering, they claim their property values have dropped.

To the Hoosier Environmental Council and its co-counsel in the Supreme Court petition, the Harvard Animal Law and Policy Clinic, that is a taking. Richard and Janet Himsel claim the Indiana RTFA has effected a taking by allowing a deprivation of the plaintiffs’ property rights to use, enjoy and exclusively possess their land.

Susan Lannon boils down the argument over the smell into simple terms. “Obviously, yes, it is a nuisance,” she explained. “Yes, it does trespass onto property.”

However, in their response briefs filed with the Supreme Court, both 4/9 Livestock and the state of Indiana argue the plaintiffs have no legal basis for their claim. A taking has not occurred, they said, because odors and fumes have never been found by the courts to constitute a permanent physical invasion of property.

Indiana told the Supreme Court that the plaintiffs have failed to argue that “the Constitution secures an inviolable right against unwanted smells.”

Braun called the plaintiffs’ takings claim “a poorly executed legal argument.” He said they have not established any personal injury claim and he disputed their assertions that their property values have declined.

Braun called the plaintiffs’ takings claim “a poorly executed legal argument.” He said they have not established any personal injury claim and he disputed their assertions that their property values have declined.

Moreover, Braun, echoing Janzen, said Indiana’s RTFA does allow for nuisance claims but his clients have not violated the law because they have not committed a negligent act.

“You don’t get to file a lawsuit in hopes of finding a claim,” Braun said. “The plaintiffs can’t identify a single act of negligence by any of the defendants.”

Ferraro pushed back. While the Indiana RTFA does contain an exception to the immunity clause if a farm is being operated negligently, the law does not cover air emissions and noxious odors. The defendants are complying but only because the statute as written does not regulate air quality, which is the source of the harm in the Himsel case, she said.

After SCOTUS

Roger McEowen, professor of agricultural law and taxation at Washburn University School of Law in Kansas, is not confident the U.S. Supreme Court will select the Himsel case. Still, he sees a correlation between the immunity being argued in the Indiana case and the issue in Bormann v. Board of Sup’rs In & For Kossuth County, 584 N.W.2d 309 (Iowa 1998). In Bormann, the Iowa Supreme County ruled a state law that essentially prevented nuisance lawsuits from being filed against large hog operations and farms violated the federal Takings Clause.

“Clearly in my mind, the Indiana law is unconstitutional,” McEowen said. “Whether the U.S. Supreme Court takes (Himsel) is an open question.”

If the nine justices do not hear the Himsel dispute, Ferraro said the effort to change Indiana’s RTFA would have to shift to the Statehouse. The law should be amended to “make ‘significant change’ actually mean ‘significant change,’” she said.

Braun already sees a need for the Indiana General Assembly to act. He advocates adding another provision to RTFA to enable farmer defendants to recover attorney fees from parties who bring “frivolous lawsuits.”

Already judges can award costs and fees, but Braun believes having specific language in the statute would give the courts more comfort in exercising their discretion.

Robert Lannon has no interest in carrying the fight beyond the Supreme Court, but in taking a plain reading of the law, he wonders why the CAFO down the road is not negligent. Indiana’s RTFA was written to support farms, he said but “it didn’t say anything about protecting factory farms.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.