Subscriber Benefit

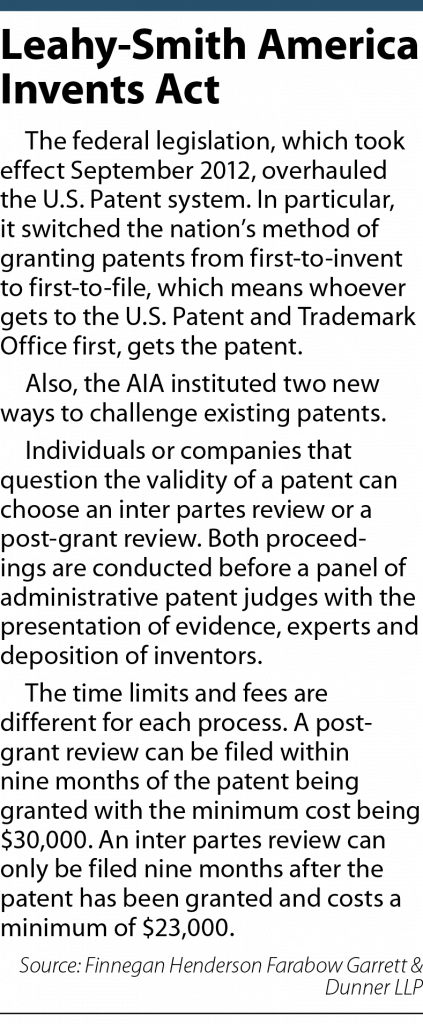

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowSince the patent system was overhauled by the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, lawsuits questioning the constitutionality of the process for challenging patents have sprung up so often that attorneys say the arguments usually invite an eye roll in disbelief.

However, on Halloween 2019, one of those constitutional lawsuits not only convinced a federal appellate court but also inspired the judges to offer their own fix to the statute. All three parties to the case petitioned for an en banc rehearing, which the court denied in a March 23, 2020, per curiam order that included five separate opinions written and joined by different combinations of the federal circuit’s judges.

Norman Hedges, director of the Intellectual Property Law Clinic at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, described the Halloween ruling as a “very, very unusual decision.”

The focus of the case was the inter partes review process that was created by the America Invents Act and is part of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Under the IPR, patents or certain claims in a patent can be challenged in a quasi-litigation proceeding. A panel of three administrative patent judges, chosen from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, hears the case with the parties being able to present experts and do more discovery than previous procedures allowed.

At issue before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit was the manner in which individuals are selected to serve as administrative patent judges. The appellate court agreed the appointment of the APJs was unconstitutional but, in an odd step, tweaked the statute to make the judges at-will employees.

To avoid a complete upheaval of the patent system, the court limited the impact of its decision. The only cases that will need to be reheard are those that are still pending in the inter partes review process and those that raised the constitutionality issue on appeal.

Because the Federal Circuit put some guardrails on its ruling, Hedges does not see much confusion and chaos coming. The wild card is the potential for the U.S. Supreme Court to take the case and offer its own opinion, but even if the justices affirm the appointments are unconstitutional and overturn the lower court’s statutory change, the result would likely be some delays in the process.

“Practically speaking, in the long run, I don’t think it will be all that monumental,” Hedges said.

Principal or inferior

The case arose from a dispute between medical device makers. Smith+Nephew Inc. and ArthroCare Corp. challenged certain claims in a patent held by Arthrex Inc. that covered a knotless suture securing assembly, according to court documents. At an inter partes review, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board ruled the claims were, in fact, unpatentable.

The case arose from a dispute between medical device makers. Smith+Nephew Inc. and ArthroCare Corp. challenged certain claims in a patent held by Arthrex Inc. that covered a knotless suture securing assembly, according to court documents. At an inter partes review, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board ruled the claims were, in fact, unpatentable.

Arthrex appealed to the Federal Circuit, arguing the constitutional issue in Arthrex, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc., ArthroCare Corp., 18-2140.

Under the America Invents Act, the administrative patent judges are appointed by the Secretary of Commerce in consultation with the director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. However, the Federal Circuit found that method of appointment was unconstitutional and, in fact, the APJs should have been appointed by the president with Senate confirmation.

The Federal Circuit so reasoned that because the PTO director does not have the power to review, nullify or reverse a final written decision by a panel of administrative judges, the judges are principal officers.

Looking for a way to prevent the inter partes review process from being upended by its decision, the court followed the suggestion of the U.S. government, which was an intervenor in the appeal. The appropriate remedy for the constitutional violation, according to the court, was to invalidate some of the statutory limitations on removing an administrative patent judge. By severing the restrictions on booting APJs, the court concluded the administrative judges would then be inferior officers rather than principal officers.

“Although the (PTO) Director still does not have independent authority to review decisions rendered by APJs, his provision of policy and regulation to guide the outcomes of those decisions, coupled with the power of removal by the (Commerce) Secretary without cause provides significant constraint on issued decisions,” Judge Kimberly Moore wrote for the unanimous panel.

After denying the rehearing petitions, the Federal Circuit denied a motion to stay its order while the parties seek a review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Dennis Schell, member in the Indianapolis office of Frost Brown Todd LLC, said the inter partes review is a good approach to addressing challenges to patents, but the process still needs some improvements.

The IPR was instituted to streamline the system for determining the validity of patents. Compared to waging a patent battle in the courts, the inter partes review process is, comparatively, quicker and less expensive.

Still, the process has spurred many patent owners to file more constitutional challenges than Schell said he anticipated. Patent owners think the process is detrimental to them and their patents, but Schell disagrees. He sees the struggles patent holders are facing as an indication that petitioners are not filing challenges unless they are reasonably sure they will win. Also, it could be a sign that patent examiners are granting patents to more applications than they should.

Statistics show patent owners face long odds in IPR proceedings. Testifying before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property and the Internet in November 2019, John Whealan, the former solicitor to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, said more than 1,400 petitions for inter partes review are filed each year, and in the final IPR decisions, some claims are invalidated 80% of the time.

Rather than toss inter partes reviews altogether, Schell offered a few suggestions to improve the process. In particular, he said, patent owners should be given more ability to amend their claims during the IPR process.

Also, if the PTO director is given the authority to review and revise the administrative judges’ decisions, then the parties should have the opportunity to present additional arguments or at least file briefs before the director issues a final ruling.

“The Federal Circuit did the best they could with trying to preserve the current system as much as possible,” he said. “But they seemed to also invite legislators to go further than the court had latitude to.”

Congressional action debated

Members of the patent bar are not unified on whether Congress should step in or let the courts work out the questions surrounding the inter partes review.

The House Judiciary subcommittee’s hearing was specifically called in response to the Arthrex ruling. Robert Armitage, former senior vice president and general counsel for Eli Lilly and Co. in Indianapolis, was among those who testified, and he saw an opportunity for Capitol Hill to revisit the America Invents Act.

Armitage suggested Congress split the Patent Trial and Appeal Board into a Patent Appeal Board that would hear ex parte appeals from decisions the patent examiners made during an ex parte prosecution of a pending patent application, and a Patent Trial Board that would handle all contested cases. Essentially, the PAB would be doing work similar to that done by appellate judges while the PTB would be doing trial work.

Armitage pointed out his proposal kind of reverts to the pre-1984 structure where the Board of Patent Appeals was devoted to ex parte appeals and the Board of Patent Interferences handled only contested interference matters. “For sound policy reasons,” he told the subcommittee, “it may be desirable for aspects of this history to repeat itself.”

Thomas Walsh, partner with Ice Miller in Indianapolis, said the IPR is a good tool in theory, noting several people are alarmed by the number of patents invalidated through the process.

That concern has nurtured some of the constitutional challenges to the inter partes review, but the U.S. Supreme Court, so far, has not been receptive to those arguments. Most recently in Oil States Energy Services v. Greene’s Energy Group, 584 U.S. ___ (2018), which raised the question of whether actions to revoke a patent must be tried in an Article III court before a jury, a majority of the justices found the IPRs do not violate Article III or the Seventh Amendment of the Constitution.

Patents are key to fortifying the financial support companies and startups need. For small inventors, the only way to secure capital for a project is to demonstrate the intellectual property is protected. For larger businesses, having patented products gives them the ability to recoup the potentially hundreds of millions of dollars spent on research and development.

As to whether Congress should revamp the IPR process, Walsh did not see a pressing need for action. “As far as I’m concerned, there are some other things more broken that Congress should be spending its time on,” he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.