Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

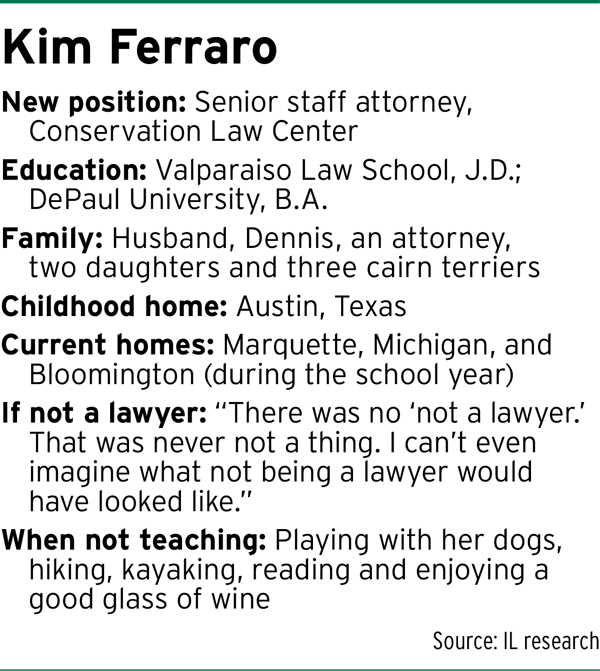

Environmental law attorney Kim Ferraro might have only been half-joking when she claimed that if she had known at the start of her career what she knows now, she probably would have chosen a different practice area.

“Had I really known what I was getting into, I might have thought a little harder about it,” Ferraro said. “I really had a very idealistic, innocent view about what I was doing. (I thought), ‘I’m going to save the world and use this law degree that I have to really help people.’ It was scary, a slog, a lonely journey.”

Yet, more than 20 years after she earned her J.D. degree as a 40-something and built a career representing homeowners and neighborhoods in fights over clean water, clean air and clean land, Ferraro is still fighting. And this summer, she expanded her work to include teaching the next generation of environmental law attorneys.

Ferraro joined the Conservation Law Center after 11 years at the Hoosier Environmental Council. On the second floor of the Lewis Building across the street from the Indiana University Maurer School of Law in Bloomington, she now has a spacious office and a busy schedule. Her time is divided between leading the litigation work undertaken by the CLC and educating, mentoring and encouraging the law students who are studying at the CLC’s Conservation Law Clinic.

The attorney’s message to students is likely one she has regularly muttered to herself when she wondered about her career choice: Don’t give up.

“This public interest practice needs you. There’s not enough of us,” Ferraro said, explaining a lesson she hopes to pass along to the students. “The other side has armies. So to protect the environment, we need you. It’s a worthwhile career.”

Being an environmental lawyer requires not just an appreciation for the natural world, but also a patience to delve into materials like the Army Corps of Engineers Wetlands Delineation Manual, along with learning the hard science underlying environmental issues.

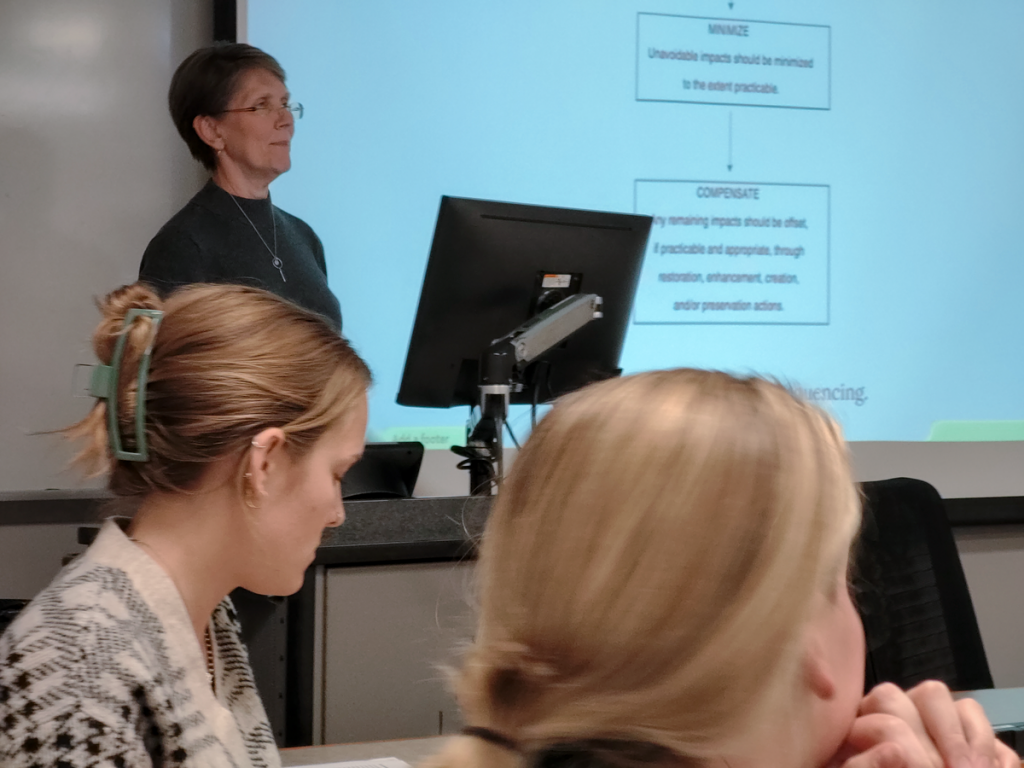

One recent Thursday afternoon, Ferraro commenced teaching those skills as she led about 10 law students through a presentation on wetlands. She anchored the discussion of complicated concepts with a lawsuit the CLC is currently litigating against Natural Prairie Farmland Holdings and the Army Corps of Engineers.

One recent Thursday afternoon, Ferraro commenced teaching those skills as she led about 10 law students through a presentation on wetlands. She anchored the discussion of complicated concepts with a lawsuit the CLC is currently litigating against Natural Prairie Farmland Holdings and the Army Corps of Engineers.

The center is representing the plaintiffs in their lawsuit against Natural Prairie’s 4,350-dairy cow concentrated animal feeding operation in Newton County. Ferraro stood in front of a large screen that displayed aerial photos of the CAFO and excerpts from court documents.

When a student asked why the Natural Prairie operation was categorized as farm wetland and not as crop wetland, Ferraro smiled broadly and said, “Look at you.” Then she acknowledged it is a complicated topic that took her two years to understand.

Getting started

Christian Freitag, executive director of the CLC, oversees the clinic. Litigation is not always the right tool to address environmental problems, he said, but when a lawsuit is the “best and even only way,” the clinic relies on attorneys like Ferraro and the students to execute the case.

“A better tomorrow is never guaranteed, and I think people feel that way now more than ever,” Freitag said. “Things only get better when individuals put their noses to the grindstone and work for it as with everything.”

Lawyers, he said, are an important part of making things better.

Ferraro is helping prepare the next generation of environmental lawyers but, ironically, as a law student, did not study environmental law. Her alma mater, Valparaiso Law School, did not have classes in that subject, so she took every course that related to the topic and educated herself because she never wanted to be any other kind of attorney.

She had to continue improvising when she graduated in 2007, relying on her J.D. and her years of work as a paralegal. Not having the legal education pedigree to secure a job at a national organization, Ferraro formed her own nonprofit, Legal Environmental Aid Foundation, and focused on helping disadvantaged communities impacted by pollution.

As with her work now, the challenge was not finding clients but choosing which cases to take.

One of the earliest lawsuits Ferraro filed was a class action on behalf of Elkhart County residents who lived near the then-VIM Recycling Center, which had “thousands of tons” of material wastes “dumped on the bare earth.” The plaintiffs were suffering from a variety of respiratory ailments allegedly caused by the “dumping and processing of the waste materials.”

For six years Ferraro litigated the case, Greene, et al. v. Will, et al., 3:09-cv-00510. She eventually got the plaintiffs an undisclosed settlement from the new owners and a $50.6 million default judgment against the former owner.

“It can be such a passionate, fulfilling (career),” Ferraro said of public interest environmental law. “Even though you’re not going to make the salary, you’ll go to bed at night just feeling so good about what you do.”

Kacey Cook became an attorney at the CLC after studying at the clinic during her second and third years at IU Maurer. In addition to the support she provides on projects involving policy initiatives, transactional work and litigation, she was in class and participating in Ferraro’s wetlands presentation.

Cook credits her clinical experience with easing her transition into practice: “I was able to see how the laws and regulations we were learning about in class were playing out in communities and (in) the strategy of public interest attorneys working to address environmental issues within those legal and social contexts.”

‘Fire and passion’

After the class ended, Ferraro took a seat and, along with Cook and CLC fellow Megan Freveletti, unwrapped and ate pieces of homemade caramel candy.

Ferraro said she enjoys working with students because they have an excitement that counters what she referred to as her jaded view. Environmental litigation, she said, is especially difficult because of the hardball tactics some industry lawyers employ.

For example, in battle over an 8,000-hog CAFO, the plaintiffs were slapped with a counterclaim for filing what the defendants called a “frivolous, unreasonable and groundless” lawsuit.

The counterclaim was dismissed, but Ferraro said she worries such antics will deter citizens from filing complaints. Knowing that all her students will not pursue public interest work, she said she hopes those who go into private practice will help their clients protect the planet.

Freveletti concedes environmental law can be pretty deflating at times. Even so, she became committed to public interest work specifically to protect the natural world during her four semesters studying at the clinic while she was a student at IU Maurer.

Working in “real time with real clients” was the “most formative and best experience” of her law school career, she said.

Freveletti’s duties now include working with Ferraro on the Natural Prairie case, helping with depositions and legal research along with assisting other attorneys at the center and teaching the students.

While Ferraro draws energy from the lawyers-to-be, Freveletti noted the students are energized by the CLC leaders’ “fire and passion.”

“I think it’s inspirational and aspirational,” Freveletti said.

“They are what inspires me to be a better advocate for the environment,” she continued, “and what I aspire to be as an attorney.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.