Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe last decade has been fraught with economic uncertainty, as a recession, recovery and an expected new recession have cast a shadow over many industries, including the law. But recent data from the American Bar Association indicates the ups and downs haven’t kept people from the practice.

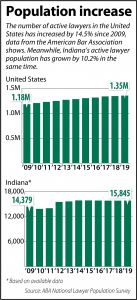

According to the ABA’s National Lawyer Population Survey, the number of active lawyers nationwide grew by 14.5% in the last decade, up from 1,180,386 in 2009 to 1,352,027 in 2019. The number of Indiana lawyers likewise grew 10.2%, increasing from 14,379 to 15,845.

These numbers can be seen as a reason to celebrate in a profession that was hit hard by the Great Recession. Law school enrollment, for example, took a nosedive in the early 2010s but has remained relatively steady ever since.

But industry experts also see a potential mismatch between lawyer supply and demand, creating the risk for oversaturation. Indeed, though the employment rate for recent law school graduates is up, the actual number of jobs has declined.

“It’s impossible for anyone to know what’s going to happen in terms of an event that might disrupt the economy,” said James Leipold, executive director of the National Association for Law Placement. “But if there’s another significant slowdown, not even as dramatic as the last one, we could see the job numbers fall more quickly.”

Given the conflicting data, experts say the best thing law students, schools and employers can do is keep an eye on the market.

Differing data?

Analyzing the legal job market isn’t as simple as looking at the lawyer population, experts say. The number of licensed attorneys has increased, but law school applications and enrollment have experienced multiple years of decrease.

Plus, the number of jobs available to new graduates fell by 150 jobs between the Class of 2017 and the Class of 2018, according to NALP data. Given this disparity, Leipold said it can be hard to reconcile why the number of lawyers is going up.

Bill Henderson, the Stephen F. Burns professor of law at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, wasn’t surprised to see that the number of licensed attorneys was up, but he agreed those numbers should be put in context.

For example, Henderson noted many retirement-age attorneys are choosing to continue working. Kellye Testy, president and CEO of the Law School Admission Council, also said the last recession has played a part in some older lawyers declining to leave their jobs. Further, she noted that technology now gives older attorneys the option of continuing their work from home.

Increasing interest?

Leipold also pointed to the law school “bubble” that popped around 2013. The recession caused about a 34% drop in law school enrollment over a four-year period, he said, but the large classes that entered the profession in the early 2010s would still be among those counted in today’s lawyer population.

Law school applications were down slightly for the 2019-2020 academic year, LSAC data shows, but the 2018-2019 year actually saw an 8.7% increase. The 2018-2019 school year also saw a 3.4% increase in 1L enrollment.

Testy said there are a few reasons why interest in law school might be rebounding. First, she pointed to what’s been called the “Trump bump,” or the idea that President Donald Trump has inspired more students to go to law school. The ABA Journal reported in 2018 that in a Kaplan survey of 500 pre-law students, 32% said the 2016 presidential election influenced them to pursue legal careers.

“If you think about what happened right after the election, it was the first time in a long time that lawyers were on the front pages of newspapers in heroic ways,” Testy said. “I think it just really sparked in the population of people coming out of college and into law school that they want to use their law degree for change and government accountability.

“They saw that role of the lawyer as making a positive difference for people,” she added.

But Testy also pointed to the “natural business cycle” of working in the law. As society gets further removed from the Great Recession, legal employers are likelier to hire, and students feel more comfortable investing in a legal education.

Too many lawyers?

Though the number of jobs available to recent law school grads has been falling, graduating class sizes have been falling faster, which is why the employment rate has been up among new lawyers, Leipold said. He noted NALP’s data tracks all jobs that recent grads take, even those at Starbucks.

Though the number of jobs available to recent law school grads has been falling, graduating class sizes have been falling faster, which is why the employment rate has been up among new lawyers, Leipold said. He noted NALP’s data tracks all jobs that recent grads take, even those at Starbucks.

“Jobs is a binary question,” Leipold said. “I either have a job or I don’t.”

Homing in on jobs in the legal field, Henderson noted the percentage of recent grads going directly into private practice has not returned to prerecession rates. NALP statistics for the Class of 2018 show 54.8% of graduates went into private practice, up 0.4 percentage points from the Class of 2017, and the closest to the 55.9% peak in 2009. The data also show the total number of law firm jobs increased by 21 jobs between the Class of 2017 and the Class of 2018.

“When you look at the percentages, that’s encouraging,” Henderson said. “But in terms of the absolute number of jobs in private practice, it’s pretty stagnant.”

Thus, Henderson’s concern is oversaturation. If the number of lawyers continues to grow but fewer graduates are finding jobs in private practice, the supply of lawyers could outpace the demand.

The professor also pointed to the stagnant levels of law school enrollment as evidence of possible oversaturation. Similarly, Leipold said the law school Class of 2021 began with more than 38,000 students — the first growth since the recession — but he does not see a need for class sizes to exceed 40,000.

Other options?

Testy describes the legal employment market as a conundrum. Job numbers are constrained, but access to justice issues are widespread. While it might not seem like there is a place in the profession for every lawyer, she said there is a great need for pro bono or reduced-fee representation in the civil realm. Henderson likewise pointed to the prevalence of pro se litigation in state courts.

Some states have responded to that conundrum by developing alternative licensing models, Testy said. She pointed as an example to Washington state, which was the first to create a limited licensed legal technician who could help with certain family law issues.

“More and more states are starting to look at models like that,” Testy said. “… They’re asking, ‘Why not be more like medicine?’ You don’t just see your M.D. — you have a nurse practitioner, somebody who cleans your teeth.”

Though the recession is nearly a decade past, Testy doesn’t expect law schools to return to their previous enrollment numbers. Instead, she said many law schools now offer degrees outside of a J.D., such as a master of laws degree, that can help them maintain the number of students and revenue they need.

“I don’t expect them to increase the number of J.D. students,” she said. “They’re trying to market to the market.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.