Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn the past, the Indianapolis Legal Aid Society could fill its staff attorney positions through simple word of mouth.

The job opening could be mentioned in conversation and resumes would soon start arriving. However, since the spring, the nonprofit — which currently has three attorney positions available — has had to become more aggressive, posting help-wanted ads on lawyer job boards, putting job announcements on social media and making plans to attend job fairs.

“We’ve never had issues like this,” John Floreancig, ILAS general counsel and CEO, said. “… It’s been very frustrating.”

The nonprofit has plenty of company. Other legal aid agencies across the state are struggling to find and hire attorneys to fill full-time staff positions. Providers speculate that lower bar passage rates and high demand for lawyers across the legal profession have created a supply issue.

Floreancig and others have noted that applicants arriving for interviews are also being courted by law firms, in-house legal departments and businesses that are looking for legal talent. The hot job market has caused legal employers in the private sector to compete by boosting salaries, creating an even bigger pay disparity with legal aid organizations, which are dependent on grants, government funding and donations.

Ironically for civil legal aid in Indiana, the shortage of lawyers is coinciding with an influx of money from a $13.1 million grant from the Indiana Housing and Community Development Authority. Legal aid groups are using the funds, in part, to hire new attorneys who will help clients with housing needs.

ILAS tries to lure lawyers by touting its benefits package and work-life balance. The nonprofit pays 100% of health insurance and contributes to individual health savings accounts as well as to 401(k)s. Still, most new attorneys and laterals appear to be making career decisions based on salary, in part because of their student loan debt.

“There’s only so much money to raise,” Floreancig said. “We’re privately funded and so what we’re struggling with now, organizationally, is do we hire less lawyers to pay more for the lawyers that are here, which then affects client services? So, we’re really between a rock and a hard place in this.”

Attorneys Max Happe in Evansville and Nell Collins in South Bend are new hires with Pro Bono Indiana. Both 2020 graduates of Indiana University Maurer School of Law have long wanted to work in legal aid and were prepared for the low pay, but they noted they are outliers because many of their classmates focused instead on private practice.

Attorneys Max Happe in Evansville and Nell Collins in South Bend are new hires with Pro Bono Indiana. Both 2020 graduates of Indiana University Maurer School of Law have long wanted to work in legal aid and were prepared for the low pay, but they noted they are outliers because many of their classmates focused instead on private practice.

While some in her class viewed legal aid as the place for lawyers who are not very skilled, Collins said most thought anyone becoming a legal aid attorney was crazy. That perception was driven by the comparatively small paychecks.

“You go to law school and you suffer through law school and you pay all this money and go into debt and then you come out on the other end and you’re just like, ‘I’m going to go help people for pennies,’” Collins explained. “It’s also draining work. You’re always dealing with people who have really severe problems. It’s not for the faint of heart.”

Mission and money

A recent survey by the National Association for Law Placement found that salaries for legal aid attorneys have risen in recent years. The median entry-level salary for a civil legal services lawyer is $57,500, an increase of $9,500 since 2018.

However, the pay hikes in legal aid have been dwarfed by the skyrocketing entry level compensation in the private sector. The median law firm salary for the attorneys who graduated last year was $131,500, according to NALP’s review of the job market for the Class of 2021.

James Leipold, executive director of NALP, said the salary numbers reflect the fierce competition in the market for attorneys. Demand for corporate legal services has grown since the economy reopened after the shutdown in spring 2020. Law firms have been scrambling to hire and are courting lawyers from across the profession, including recent graduates who want to work in civil legal aid.

“(Attorneys) who go into public interest work are mission- and purpose-driven people,” Leipold said. “They went to law school for a particular reason. They really want to do that work. They never wanted to do the big law job at $210,000 where they work all night. But we’re living in a world with 9.1% inflation year-to-date, so money has to be a consideration.”

Happe acknowledged the work of a legal aid attorney is difficult and emotionally taxing. The lawyers must realize that a win may not permanently put the client in a better circumstance. Rather, a victory in court may mean a tenant can continue living in his or her apartment for a little longer before getting evicted, but the eviction is still going to happen.

Yet even though the words of thanks do not come every day, Happe said he sees his work as “very important” because it betters the community by trying to ensure those in crisis are not left to fend for themselves.

“It gives you the sense of you’ve done something good. You have helped people who in no other way would ever get help,” Happe said. “You have been a steward of society. You have helped build a community that if not for you, it’s going to continue to let these people fall and fail and then it just kind of creates this whole network of people at a level that cannot be helped.”

For Reema Mahmood, a new staff attorney at ILAS, the opportunity to work in legal aid was the “best for me at the moment.” She graduated from Southern Illinois University School of Law in 2020 and arrived in Indianapolis with her husband, who is completing a medical residency at Riley Hospital for Children.

The work is rewarding, she said, and is also enabling her to learn many aspects of lawyering.

“Law school doesn’t really teach you real life experiences,” Mahmood said. “It doesn’t teach you about going to court, it doesn’t teach you how to give advice to clients in a way they can understand. I think if you want to sharpen those skills, it’s good to have real-life experiences, and legal aid provides that.”

Taking longer

The Legal Aid Corp. of Tippecanoe County and Indiana Legal Services, which has offices around the state, have experienced similar hiring difficulties. Luisa White, executive director of the Legal Aid Corp., and Jon Laramore, executive director of ILS, both have stories of open positions taking longer to fill because fewer attorneys are applying.

Laramore noted that although lawyers join ILS because of the work, the nonprofit is emphasizing the financial rewards because “mission doesn’t put food on the table.” The organization has given 3% pay raises annually for the last three years, maintained a “very good benefits package” that includes contributing to the 401(k), and promoted that the attorneys are eligible for the federal student loan forgiveness program.

While acknowledging the tight labor market, Laramore hesitated to use the word “shortage,” and he pointed out the supply of new attorneys has likely been reduced since Valparaiso Law School closed in 2020.

“We’re ultimately filling the positions that we have,” Laramore said. “It’s taking longer, but I can’t say that there are too few (attorneys).”

White said finding an attorney is made more complicated by the nature of the work. Legal aid lawyers are often representing clients who have mental health or addiction issues who then experience some kind of loss like an eviction or job termination. That can lead to the Indiana Department of Child Services removing their children.

Consequently, the attorneys must be able to juggle a multitude of cases and toggle between different areas of law. White noted lawyers with those skills are always hard to find, and the search may become more challenging in the years ahead.

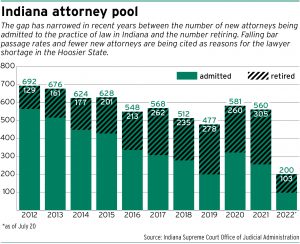

She speculated that her part of the state is struggling to find enough legal talent because fewer attorneys are passing the bar and entering the profession while more attorneys are leaving the practice of law.

“A lot of attorneys passed away or got sick from COVID. Or they’re retiring because things are just wild right now and they’ve had enough,” White said. “So it’s a combination of low passage rate of the bar and illness and retirement. There’s just not enough young attorneys and, I guess, we’re an aging population.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.