Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowHoosiers are not ones to sit at home doing nothing.

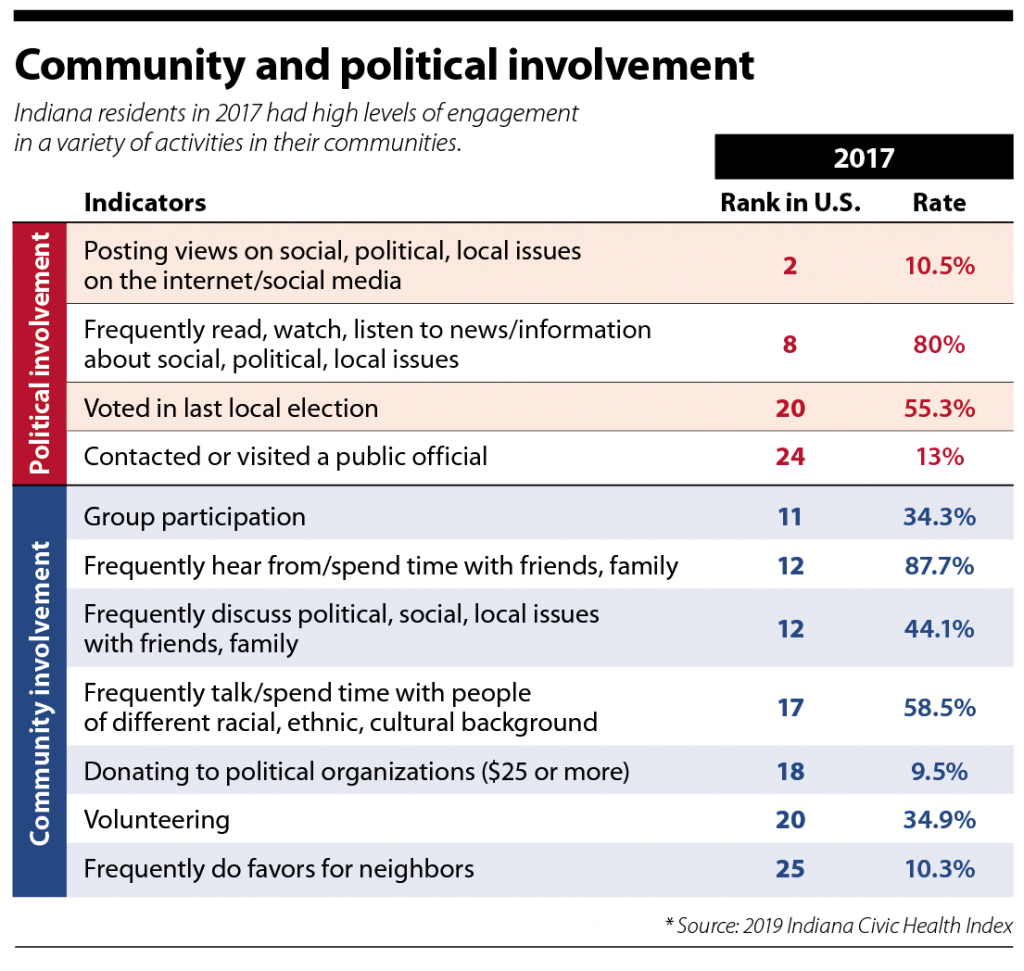

Data from the US Census Current Population Survey shows Indiana residents are among the most active in their communities and most engaged politically in the country. In 2017, Indiana ranked in the top half of all states for volunteering, doing favors for neighbors, spending time with people of different backgrounds and contacting public officials. Moreover, Indiana was among the top 10 of all states in posting views on social media and staying abreast of current issues.

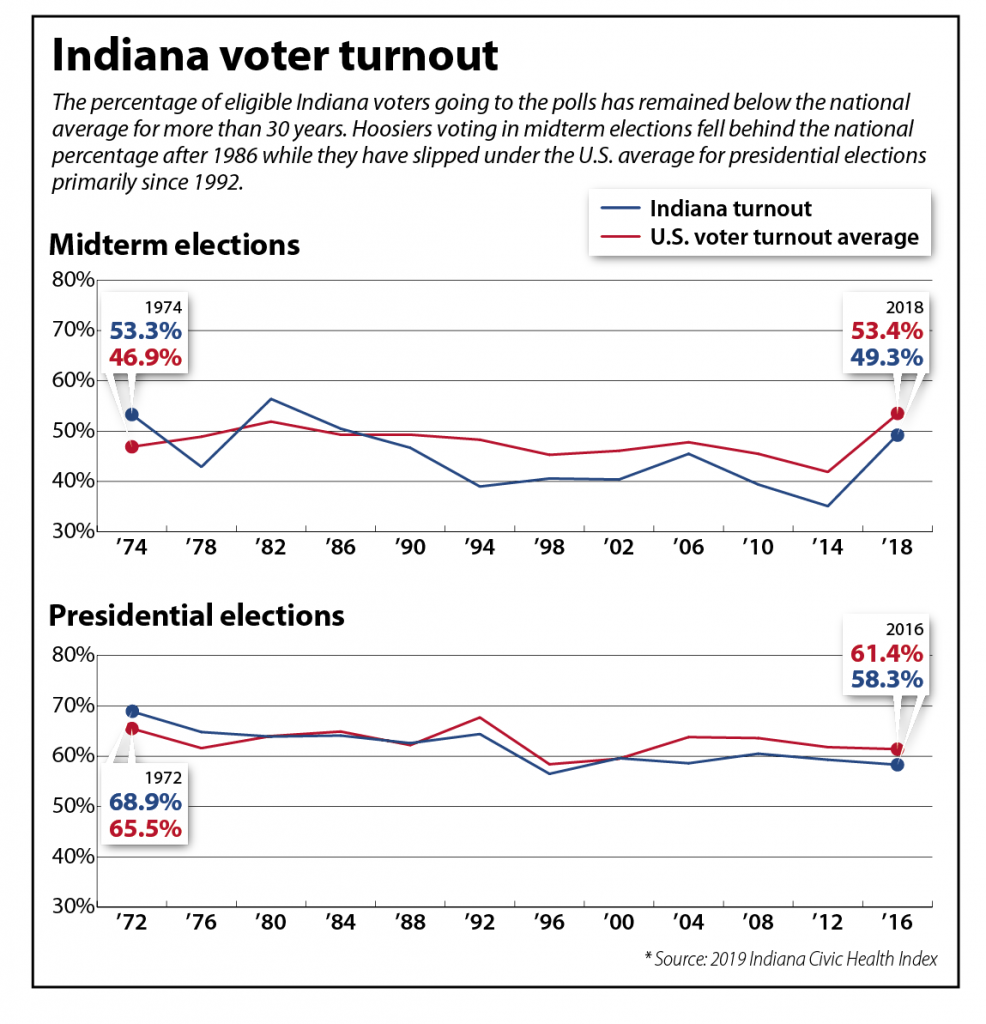

However, going to the voting booth and casting a ballot are different matters. Hoosier participation has fallen such that the state has been scraping the bottom. During the 2018 midterm election, just 49.3% of all eligible voters in Indiana participated, ranking the state 43rd in the nation.

This paradox is highlighted in the 2019 Indiana Civic Health Index released this month and underpins two recommendations to increase voter engagement. The current edition is the fourth such measure of Indiana’s civic temperature, which is now providing a clear picture of where the systemic problems are as well as pointing to where the opportunities are, according to leaders of the study.

“Why people don’t show up at the polls or on early voting is really a mystery to me, and I’m glad to see we’ve got kind of an action step to try to address it,” said former Indiana Attorney General Greg Zoeller. “Whatever the reasons are, we’ll have to find people where they are and figure out what motivates people to be more civically involved when it comes to elective politics and government.”

Zoeller helped unveil the findings in the 2019 index at a panel discussion held Nov. 11 at Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law. He was joined by retired Indiana Chief Justice Randall Shepard, Bill Moreau, a partner at Barnes & Thornburg LLP, and Charles Dunlap, executive director of the Indiana Bar Foundation.

A variety of state and national organizations collaborated on the civic health study, including the Indiana Bar Foundation, the Indiana Supreme Court and the Center for Representative Government at Indiana University. The findings presented in the index are based on the National Conference on Citizenship’s analysis of the US Census Current Population Survey data.

The two recommendations resulting from this year’s study share the same goal of creating better informed and more active voters in Indiana. First, the index proposes assembling a civic education task force to study methods of instruction, programming and outcomes to improve Hoosiers’ understanding of American democracy. Second, the index suggests increasing voter turnout significantly to move Indiana from the bottom 10 to the top 10 states during the 2020 elections.

To realize the second recommendation, turnout would have to rise by 20%, or 500,000 more Hoosiers would have to go to the polls next year. A key to that effort will be a statewide nonpartisan campaign to encourage all eligible residents to register and vote. Moreau explained the goal now is to raise “a few million dollars” to fund a series of public messages that will emphasize the Indiana issues in the next election.

“We are not going to have anything to do with the national level. There are plenty of other people doing that,” Moreau said, adding that the campaign will focus on “the stakes at the state level and what’s going on in Indiana in 2020.”

“We are not going to have anything to do with the national level. There are plenty of other people doing that,” Moreau said, adding that the campaign will focus on “the stakes at the state level and what’s going on in Indiana in 2020.”

In conjunction with next year’s get-out-the-vote push is the launch of The Indiana Citizen, a new nonprofit founded by Moreau and his wife that promotes civic engagement.

Moreau acknowledged low voter turnout benefits the people who do show up at the polls by giving their votes more impact. But, he continued, it poses a threat to the country’s ability to sustain a representational democracy when fewer and fewer citizens cast a ballot.

“What happens on a day when turnout is so low and the race is so close that we refuse to accept the outcome of the election?” Moreau questioned. “That’s a bad day for democracy.”

The civic education task force, outlined in the first recommendation, is seen as another antidote to voter apathy. Dunlap said the committee is expected to include about 15 members from diverse backgrounds and will begin its work in early 2020. It will not only take a close look at what is happening in Indiana by holding meetings around the state and getting input from local communities, but it will also examine what other states are doing educationally that might be replicated here.

A 2018 study by the Brown Center Report on American Education found Indiana has a limited civics education portfolio. While the state was said to effectively use discussion of current events, it did not incorporate service learning, simulation and new media literacy instruction. This deficiency was seen in the 2018 Advanced Placement testing results, in which only 25% of Hoosier students earned a top score of either four or five on the US Government and Politics Exam.

Dunlap said “quality, in-depth civic education” teaches basic knowledge, like who signed the Declaration of Independence, along with more complex foundational concepts, such as federalism.

Dunlap said “quality, in-depth civic education” teaches basic knowledge, like who signed the Declaration of Independence, along with more complex foundational concepts, such as federalism.

By the end of next year, the task force hopes to be able to offer its own recommendations for making civic education better and available to more students in Indiana. Dunlap said the investment in teaching about government will bring long-term rewards.

“There’s been a lot of data collected that the better the quality and earlier the civic education programs, the higher likelihood that you are going to vote and to be engaged throughout your lifetime,” he said. “From a civic education side, it’s a bit of a long process, but that will hopefully bear fruit down the road.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.