Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

A new presidential executive order that bars migrants who unlawfully cross the U.S. southern border from receiving asylum has already triggered one lawsuit and a backlash from immigration advocacy groups.

Some Indiana immigration attorneys are wondering what the order’s ultimate impact will be for recent arrivals to the U.S. residing in the state, given the confusion about current immigration law regarding asylum and the crushing backlog of cases in the country’s immigration courts.

President Joe Biden announced the order June 4.

The order goes into effect when the number of border encounters between ports of entry hits 2,500 per day and daily averages already are higher now. Average daily arrests for illegal crossings from Mexico were last below 2,500 in January 2021, the month Biden took office, the Associated Press reported.

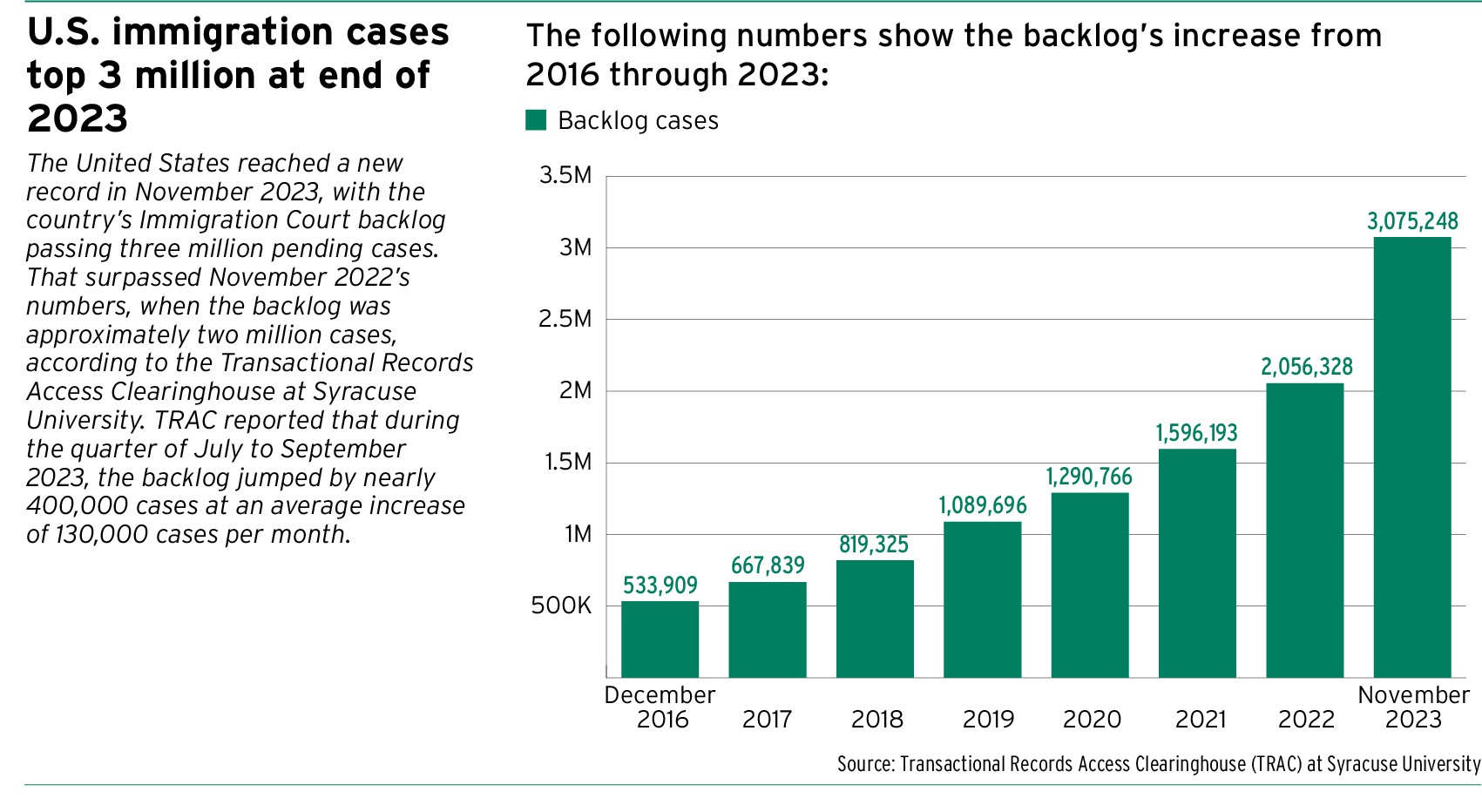

The order comes at a time when the country’s immigration cases are facing a record case backlog, with more than three million pending cases, the nonpartisan Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University reported in December 2023.

TRAC calculated that the average caseloads of the 682 judges now on the immigration court bench have jumped to 4,500 per judge.

Rachel Van Tyle, director of legal services at Exodus Refugee Immigration in Indianapolis, said she thinks the order is going to divert even more resources from the immigration courts and further delay pending cases.

“If it were me, I’d focus on getting adjudication rates to be faster,” Van Tyle told Indiana Lawyer.

Van Tyle said the Chicago immigration court, which handles all Indiana immigration cases, is pretty backed up, with some cases taking four to five years or longer to be adjudicated and some people waiting as long as 10 years to get interviews for asylum cases.

When she started practicing in 2012, it usually took only six weeks to get an interview, Van Tyle pointed out.

Biden order draws lawsuit on behalf of immigrants

Erin Warrner, an immigration attorney with the Law Office of Jesse K. Sanchez in Indianapolis, called the order “asylum ban 2.0,” noting its similarities to an order issued by former President Donald Trump.

As an attorney looking at the order on a philosophical level, Warrner said she felt it flew in the face of existing U.S. and international law regarding a person’s right to seek asylum when they are fleeing persecution.

“To ban people who are not crossing at a port of entry, but have arrived in the U.S., is illegal,” Warrner said, stressing that the U.S. Constitution protects individuals and their due process rights.

Warrner said there had already been a lawsuit filed that challenges the order.

The Associated Press reported that a coalition of immigrant advocacy groups sued the Biden administration over Biden’s recent directive that effectively halts asylum claims at the southern border, saying it differs little from a similar move by the Trump administration that was blocked by the courts.

The lawsuit — filed by the American Civil Liberties Union and others on behalf of Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center and the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services, or RAICES — is the first test of the legality of Biden’s sweeping crackdown on the border, which came after months of internal White House deliberations and is designed in part to deflect political attacks against the president on his handling of immigration.

“The United States has long sheltered refugees seeking a haven from persecution. The 1980 Refugee Act enshrined that national commitment in law. While Congress has placed some limitations on the right to seek asylum over the years, it has never permitted the Executive Branch to categorically ban asylum based on where a noncitizen enters the country,” the groups wrote in the complaint.

According to AP, Biden invoked the same legal authority used by the Trump administration for its asylum ban, which comes under Section 212(f) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. That provision allows a president to limit entries for certain migrants if their entry is deemed “detrimental” to the national interest.

Warrner said, logistically, there’s only so many people to staff the border and only so many beds for migrants that have been detained.

The attorney said she thought there will be some people that will be released into the United States due to legal exceptions to the order.

As an attorney, Warrner said she is most concerned about the issue of due process for people trying to enter the country and their overall safety.

“People are in just these incredibly dangerous situations they’re fleeing and dangerous conditions,” Warrner said.

Indianapolis immigration court?

Attorneys interviewed for this story said they had heard a new Indianapolis immigration court is still in the works, but its opening had been delayed.

Kathryn Mattingly, a press secretary for the U.S. Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review, told Indiana Lawyer in an email that EOIR would announce any additional details on new immigration courts through a public notice, which would be posted on the office’s website.

In June 2023, a statement from the EOIR office to Indiana Lawyer announced that the immigration court planned for Indianapolis was expected to open by summer 2024.

It read: “We expect to have seven courtrooms and about 40 employees at the facility, including immigration judges and other court staff. The Indianapolis Immigration Court will be located in the Minton-Capehart Federal Building, an existing federal building. Additional details on the timeline, hiring plans, or caseload are not available at this time. EOIR constantly monitors its caseload nationwide to meet the needs of all those with business before the agency; opening new immigration courts in high-volume areas is one way to meet our stakeholders’ needs,” the EOIR said in a written statement.

When asked by Indiana Lawyer about the current timeline for the Indianapolis court’s opening and staffing levels there for the Office of Principal Legal Advisor, Erin Bultje, a U. S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement deputy press secretary, said she would look into the matter. Bultje did not respond by IL’s deadline.

Katie Rosenberger, an attorney with Indianapolis-based Villarrubia & Rosenberger, P.C., said the latest information she’s heard is that the new immigration court will open sometime this fall.

She said she thought the executive order could result in quite a few people with credible fears and reasons for seeking asylum in the U.S. to be returned to their home countries.

“It’s not necessarily an effective way to reduce crossings and entries into the U.S.,” Rosenberger said of the Biden order.

Rosenberger also emphasized that a lot of migrants don’t have the luxury to wait months after they have scheduled an appointment while they’re in Mexico through the CBP One app to present themselves at an official border crossing point to seek entry.

In the ACLU lawsuit, advocates detailed a list of complaints about the app. For example, many migrants don’t have a cellular data plan or the Wi-Fi access needed to use it. Some migrants don’t speak one of the languages the app supports, while other migrants can’t read. And there’s only a limited number of slots available every day compared with the number of migrants who want to come into the country.

There is a huge number of recent arrivals to the U.S. that have come to Indiana, Rosenberger noted.

Like Warrner and Van Tyle, Rosenberger said she wasn’t sure yet what the practical impacts of the executive order would be on those arrivals.

The Chicago court has put specific dockets in place for recent arrivals, Rosenberger said.

“They are taking steps to reduce the docket backlog, but it’s still pretty significant,” Rosenberger said, adding that the court had also increased its number of judges.

Rosenberger said the chief immigration judge in Chicago stated that once the Indianapolis court opens, the Chicago court will entertain motions to change venue for Indiana immigration cases.

With all of the uncertainty surrounding immigration and the national case backlog, Rosenberger said how long an individual has to wait to get their case resolved varies from person to person.

She said, in one extreme immigration case, she has one client that entered the United States in 2012, has only been to court once and has been separated from his spouse and child for more than a decade as he waits for a resolution.

“The delays have had some really significant and tragic consequences,” Rosenberger said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.