Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhen the immigration court scheduled the trial for October 2020, Evansville attorney David Guerrettaz remembered thinking that date was light years away.

Guerrettaz, partner at Ziemer Stayman Weitzel Shoulders LLP, was representing an asylum seeker from Africa at her initial hearing before the Chicago immigration court in 2016. Four years between court dates is a long period, but in immigration court, a lag of three to five years from one hearing to the next has become normal if not expected, attorneys say.

As October drew closer, Guerrettaz was hopeful the hearing would take place as scheduled. He had been building the case file, adding new information and staying in contact with his client during the intervening years. Everything was ready to help the client explain to the court why she did not feel safe to return to her home country.

Then about five days before the hearing, the case was postponed.

Guerrettaz has been calling the court hotline but, so far, he has not received any update on the case or the new hearing date.

“A lot of clients will assume the worst,” Guerrettaz said, explaining the immigrants live in limbo and their anxiety grows as they await hearings scheduled so far out. “They think the long wait must mean the court really dislikes their case.”

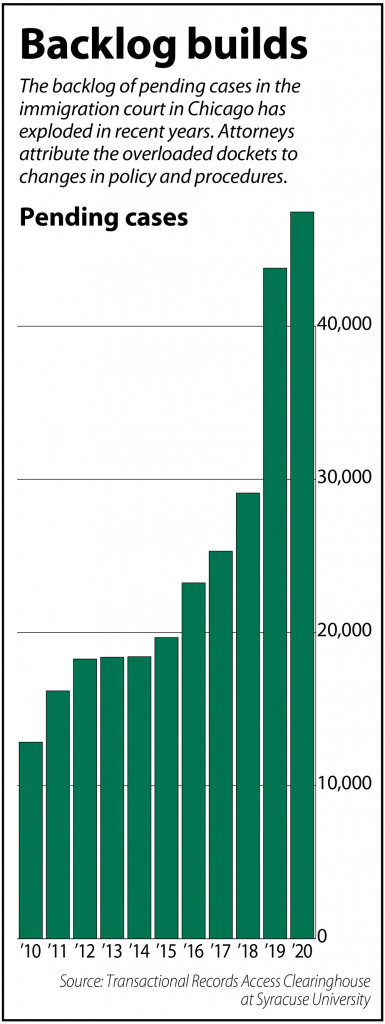

However, the problem in the U.S. Immigration Court has little do with the individual cases. Rather, attorneys contend the lengthening time between hearings and the growing delays are induced by changes in policy and procedures needlessly clogging the docket and causing the backlog to skyrocket. Since fiscal year 2017, the number of pending cases has more than doubled from 629,051 to 1.26 million for fiscal year 2020.

In Chicago, the number of pending cases reached 47,462 at the close of the fiscal year on Sept. 30, 2020. The average number of days the cases are pending in the Windy City hit 953 in fiscal year 2020, which is down from the high of 1,018 days in fiscal year 2017.

In Chicago, the number of pending cases reached 47,462 at the close of the fiscal year on Sept. 30, 2020. The average number of days the cases are pending in the Windy City hit 953 in fiscal year 2020, which is down from the high of 1,018 days in fiscal year 2017.

Cecilia Monterrosa of Monterrosa Law Group in South Bend said the Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration has slowed the immigration court’s ability to move cases along. She pointed to the drop in deportations as a sign that changes in the court’s operations are gumming the process.

The number of removals under Trump hit a high of 267,258 in fiscal 2019, the most recent data available from Immigration and Custom Enforcement. Comparatively, during the Obama Administration, the average number of individuals removed each year was 343,713.

In particular, immigration attorneys say the elimination of prosecutorial discretion to allow U.S. Department of Justice attorneys to drop cases and the inability of judges to administratively close cases adds to the backlog. Also, the high turnover in immigration judges and the shutdown of the courts because of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the situation.

Monterrosa said the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Attorney General may believe the changes they have made in immigration policy will make a big difference. But she noted what might work in theory is not working in practice and is overloading the dockets.

Practice and procedure

The work Guerrettaz put into the asylum case demonstrated why frustration can follow a delay.

As with other clients he has defended in immigration court, Guerrettaz met with the woman a few months before the hearing date. He interviewed the witnesses, made sure the exhibits complied with court rules, and prepared and filed the briefs.

Now the postponement can impact the quality of the case. Evidence becomes old while witnesses can relocate and become unavailable. Although not common, it is possible for the condition of the home country to improve during the wait time so the immigrant’s fears of being harmed upon return might not be as persuasive.

When asked if all his time and effort put into the asylum case was for naught, Guerrettaz’s voice dropped as he uttered the single word, “yeah.”

Attorneys saw the burden on the immigration courts increase after the interim decision in Matter of Castro-Tum, issued by former U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions. The May 2018 decreed eliminated administrative closures in immigration proceedings.

A practice advisory from the National Immigration Justice Center described administrative closure as a “docket-management tool.” Judges could temporarily remove a case from the court while the respondent sought another form of relief such as a visa.

Giving judges discretion to decide which cases to essentially make inactive helped ensure the limited resources of the court were being focused on the most important cases, attorneys explained. However, Sessions’ decree slammed the brakes on the practice. Data from Syracuse University shows administratively closed cases hit an all-time high of 57,646 in fiscal year 2016 but fell to 13,018 in fiscal year 2020.

The 7th Circuit Court of Appeals restored some of that discretion to immigration judges in its jurisdiction with the June 2020 decision in Meza Morales v. Barr, 19-1999.

Still, Sarah Burrow, immigration attorney at Lewis Kappes P.C., believes courts are taking shortcuts which is fueling her fear that due process will become a casualty. For example, trials that previously had been allotted a half-day have been reduced to one hour.

“Sometimes I push back,” Burrow said. “I have always maintained this is my client’s one opportunity to share his or her life story with the judge. My position is I will not permit the court to rush my client through that opportunity.”

In another instance, because of cutbacks in the immigration courts, an interpreter for her client was attending a hearing telephonically rather than in-person. Burrow, who is bilingual, quickly caught a severe mistake. Her client told the court he had rolling papers in his pocket but the interpreter relayed the client had said he had drugs.

Burrow interrupted and was able to get the record corrected. She noted if she had not understood her client, he could have been facing more serious charges for having a controlled substance rather than a misdemeanor for possession of drug paraphernalia.

Independence

Despite the policies that have created more barriers to citizenship, Monterossa said advocates for immigrants have scored some victories.

The ruling in Meza Morales is one victory along with another 7th Circuit decision that let stand a preliminary injunction against the federal government’s public charge rule. In Cook County, Illinois, et al. v. Chad F. Wolf, Acting Secretary of Homeland Security, et al., 19-3169, the majority affirmed the lower court’s ruling that the executive branch could not deny entry to anyone who was determined to likely need public assistance such as food stamps and Medicaid at some point. Now-U.S. Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett dissented.

A victory for the immigration process would come by making the immigration courts independent, according to advocates within the legal community. The National Association of Immigration Judges has long called for the establishment of an independent Article I Immigration Court, and other organizations such as the American Bar Association are adding their voices, said Ashley Tabaddor, association president.

Tabaddor is an immigration judge in California but spoke to the Indiana Lawyer strictly in her capacity as the leader of NAIJ.

Currently, the immigration court is part of the U.S. Department of Justice which, Tabaddor said, creates a “structural defect” in the system. The immigration court judges have a conflict of interest because they are employed by the Justice Department just like the prosecutors practicing before them. In addition, the court is vulnerable to the swings in policy with each new White House administration.

Independence would not be a panacea, she said, but it would help reduce the backlog and prevent more cases from piling on. The immigration judges could manage their docket and run their courts without being subjected to the constant reshuffling done for political messaging.

“Judges will have true independence to make decisions and not be fearful of losing their jobs for not meeting artificial quotas and deadlines and not being able to exercise the expertise for handling the cases on their dockets,” Tabaddor said.

The consequence of keeping the immigration connected to the Justice Department is continued disfunction, Tabaddor said. There will be ongoing shifts in policy and procedures as the “pendulum swings with each new administration” and there will be “continued chaos.”

Attorneys talk of the human toll exacted by backlogs and changing directives. Immigrants already stressed and anxious must live with uncertainty for long periods of time.

“I feel it in my soul how my clients are suffering because they don’t see any end in sight,” Burrows said. “They want a decision so they know what the future holds and what options they may or may not have.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.