Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn the decade Teresa Clemmons has worked in suicide crisis intervention and prevention, she’s seen the number of calls seeking help grow and grow.

Clemmons is executive director of A Better Way Services Inc. in Muncie, one of Indiana’s three crisis centers that recently began taking calls from 988, the nation’s new suicide prevention hotline.

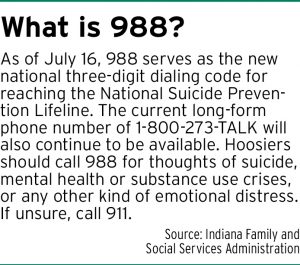

Federal legislation enacted in October 2020 designated 988 as the three-digit dialing code for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, now known as the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. The shorter dialing number went live nationally on July 16, but the previous 10-digit lifeline phone number remains available.

At the launch date, Clemmons said A Better Way saw a 50% increase in calls. That’s leveled out to about a 30% increase overall since July 16.

Her center has four employees dedicated to answering the 24/7 hotlines, fielding roughly 500 calls per week with the ability to answer about 80% of calls. They’re recruiting more staff to alleviate demand.

“It’s really a struggle,” she said.

As Indiana buckles up for the expected increase in calls through 988, conversations are beginning about how to navigate the roles of trained mobile assistance crisis teams and law enforcement.

Getting help

When people call, text or chat 988, they will be connected to trained counselors that are part of the existing Suicide Prevention Lifeline network. The counselors are trained to listen to callers, understand how their problems are affecting them, provide support and connect them to resources, if necessary.

More than 200 crisis centers have operated in the network since 2005. For its part, Indiana currently has three National Suicide Prevention Lifeline call centers — located in Gary, Muncie and Lafayette — to answer calls to 988. Hoosiers can still call from anywhere in the state, regardless of where the physical crisis center is located.

Two additional centers in Indianapolis and Fort Wayne are in the process of becoming a 988 center, according to the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration.

Christopher Drapeau, executive director of suicide prevention for the FSSA’s Division of Mental Health and Addiction, said Indiana is ready and “uniquely positioned” for the transition.

“We believe we will increase the likelihood that Hoosiers in crisis who reach out to 988 will be routed to the right remedy at the right time,” Drapeau said.

During the pandemic, Indiana lost two of its five national suicide prevention centers. At that time, in-state answer rates for calls was below the 50% range. But that figure has since increased to the 70% range, Drapeau said.

“We feel very confident in the group that exists today,” he said.

Working in tandem

Different from 911, which focuses on police, fire and medical emergencies, 988 deals with calls concerning thoughts of suicide, mental health or substance use crisis, or any other kind of emotional distress.

Vibrant Emotional Health, administrator of the suicide prevention hotline, said offering 988 “will increase the accessibility” of “life-saving interventions and resources.”

On its website, Vibrant maintains that increased collaboration between 911 and 988 can provide more options for people in crisis. That could look like dispatching mobile crisis teams to individuals in mental health or suicidal crises rather than police or EMS.

Indiana has already taken steps to meet that need in some parts of the state.

Sgt. Lance Dardeen serves as the day-to-day supervisor for the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department’s Mobile Crisis Assistance Team, or MCAT. Dardeen said the mobile assistance team began as a pilot project in 2017 between IMPD, Indianapolis Emergency Medical Services and Eskenazi Health. Data from the pilot revealed that the majority of calls came between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m. during the week and that paramedic assistance wasn’t utilized as much as anticipated.

Since then, EMS dropped out of the project and MCAT’s eight teams, coupled with Eskenazi clinicians, now respond to calls, offer resources and conduct follow-ups during its working hours, 7:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Friday.

When responding to a call placed to MCAT, Dardeen said it’s “very important” for district officers to respond as well due to potential safety concerns.

“Once the scene is safe, we do a really good job of telling those district officers, ‘Hey, I got this, you can go back into service,’” he said. “But we’d rather send the officers and not need them, then need them and not have them.”

Having 988 available may help free up law enforcement to respond to medical, fire and police calls, and prevent arrests or — in some cases — undesirable outcomes.

Indiana Department of Correction spokesperson Annie Goeller said 80% of the IDOC’s incarcerated population has either a mental health and/or substance use disorder.

Goeller said she couldn’t speak to whether having a more easily accessible mental health/suicide line such as 988 could help reduce the overcrowding of Indiana jails and correctional facilities by handling those issues before arrests are made.

Goeller said she couldn’t speak to whether having a more easily accessible mental health/suicide line such as 988 could help reduce the overcrowding of Indiana jails and correctional facilities by handling those issues before arrests are made.

Dardeen, who also serves on a state committee addressing the marketing and education of 988, said it could be a 10-year process to get everything running at full speed.

“And the thought is, if they call 988, and they don’t need police, that these individuals can go in and try to help out and assist. But I will say, I think like 80% of the calls can be taken care of without sending somebody,” Dardeen said.

The MCAT leader said conversations are being had about how to ensure calls are properly dispatched to either 911 or 988.

“As law enforcement, I think there are a lot of runs that we go on that we don’t need to go on where 988 would be completely appropriate,” he said. “So we are looking forward to that triage so we can kind of focus on more appropriate runs for law enforcement.”

Earlier this year, Indianapolis residents Gladys and Herman Whitfield Jr. called 911 to get help for their son, Herman Whitfield III, who they said was having a mental health crisis and needed an ambulance.

At the time the Whitfields called for help, MCAT’s operating hours for the day had ended. Six IMPD officers responded to the home that night, where they said they found Whitfield moving through the home naked, sweating and bleeding from his mouth.

Responding officers ultimately shot Whitfield with a Taser, handcuffed him, kept him lying on his stomach in a “prone position” and put their weight on his back before he became unresponsive and EMS intervened. His death was later ruled a homicide in an autopsy report released by the Marion County Coroner’s Office.

Rich Waples of Waples & Hanger, an attorney representing the Whitfields in their wrongful death suit filed against the officers, said the Whitfields’ call for help could haven fallen under either 911 for medical assistance or 988 for a mental health response.

“He was in distress. He was really not understanding what was going on,” Waples said. “The last thing he needed was somebody to use force against him.”

The attorney said he thinks 988 is an “awesome public service.”

“It should create efficiencies both ways,” he said. “You would think that it would free up law enforcement to do more real law enforcement-type activity and focus mental health professionals more on the crisis intervention that doesn’t require a law enforcement response. It seems like it’s a win-win situation with the division of efforts and resources.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.