Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowMaybe it ties into the tradition that friendships have been formed and strengthened over beer, but during the pandemic, Sun King Brewery has been bettering its relationship with its employees.

“I think as a company, we are more in tune with what our employees think and feel and want them to express their opinions,” said Steve Koers, vice president and general counsel at the Indianapolis-based brewery. “We’ve made it an effort to not turn any opinions away and let people talk freely and not worry about any repercussions.”

The internal steps taken to let employees know the company cares, according to Koers, has led to workers taking an ownership and viewing the beer-maker as their business, too.

The internal steps taken to let employees know the company cares, according to Koers, has led to workers taking an ownership and viewing the beer-maker as their business, too.

Paying more attention to the employees is a good strategy for companies wanting to avoid the costs and risks that come with getting sued — especially now, as businesses are facing a surge of class actions that is being fueled by labor and employment claims.

Separate analytical reports from the law firms of Carlton Fields and Seyfarth Shaw both found work-related issues are continuing to convince employees to take their bosses to court.

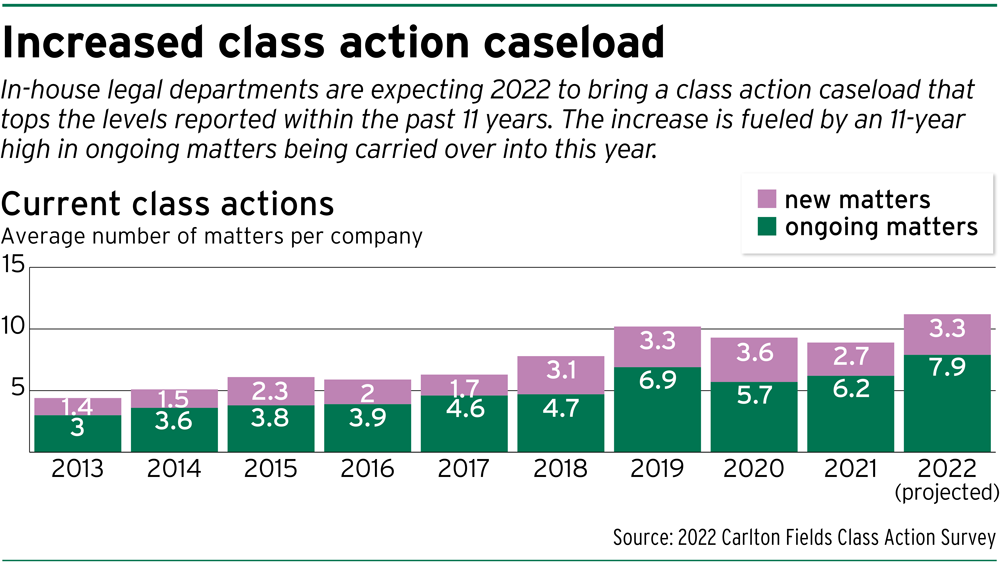

According to the 2022 Carlton Fields Class Action Survey, general counsel and senior legal officers say they are expecting their companies to have two to three new class actions filed against them this year, the highest level reported in more than 10 years. The new class actions, combined with carried-over mass litigation, are anticipated to boost the average number of legal matters per company to a record 11.2 in 2022.

As a result, class action defense spending is anticipated to keep accelerating after crossing the $3 billion threshold for the first time in 2021.

John Clabby, shareholder in Carlton Fields’ Tampa, Florida, office, said he has noticed a shift that may indicate a new normal. In the 2021 survey, in-house attorneys saw all the class actions, whether from employees or consumers or product liability, as being linked to COVID-19. But this year, the legal departments are viewing COVID-19 issues as routine and something that will continue to impact the budget and risk profile for their companies.

“The same company that’s navigating how to handle COVID-19 could face at one extreme a class action for a mask or a vaccine mandate and at the other extreme a potential class action … for not having a mask mandate or vaccine mandate,” Clabby said. “So this is the challenge that has been put on our in-house legal professionals, and it’s very hard.”

Fuel for ignition

Attorneys at the employment law firm of Ogletree Deakins Nash Smoak & Stewart say they have seen most of their predictions come true as to the issues and areas that will likely bring litigation. But Jenn Betts, managing shareholder of the firm’s Pittsburgh office, said no one anticipated employees leaving their jobs at such a rate as to create the monumental shift now known as the Great Resignation.

Departures, Betts said, fertilize the ground for class actions because, without a connection to the workplace, employees are more likely to sue a past boss than a current one. In class actions, once a court certifies the class, notices will be sent to anybody who falls within the defined group, and with former workers not seeing a risk to their paychecks by opting in, companies could face a case that has thousands of plaintiffs and runs into millions of dollars in damages.

“Again, once you’ve left and you feel like you were treated wrongly, you’re more likely to pursue litigation or want to join a case that somebody else files than if you’re currently actively in the workforce and trying to work it out with your employer,” she said.

Disgruntled former employees may be the fuel, but class actions are being ignited by the federal government and the plaintiffs’ bar.

As Gerald Maatman, partner at Seyfarth Shaw and general editor of the 2022 edition of Seyfarth’s Annual Workplace Class Action Litigation Report, explained, agencies like the U.S. Department of Labor have been more aggressive about implementing and enforcing rules and regulations that are protective of workers. This is helping stir the plaintiffs’ attorneys, who see not only more openings for lawsuits because of government enforcement actions but also the success other lawyers are enjoying with labor and employment class actions.

Companies are getting squeezed as the monetary value of workplace class action settlements has exploded, the Seyfarth report noted. In 2021, the top 10 settlements in employment-related class actions topped $3.62 billion — more than double the $1.58 billion in 2020.

“In my 40 years of handling these sorts of cases, I’ve never seen anything like I’ve seen in the last 12 to 18 months,” said Maatman, who co-chair his firm’s class action litigation practice group.

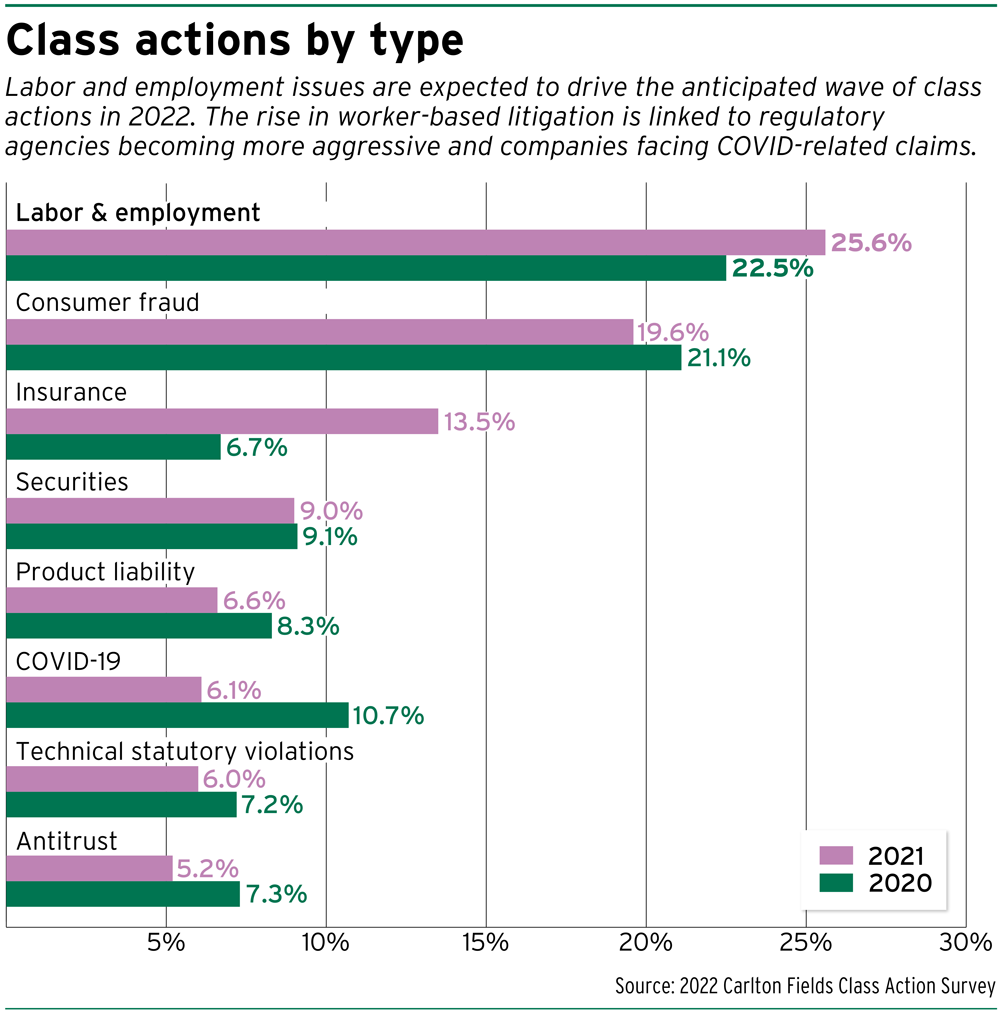

The Carlton Fields survey noted labor and employment matters dominate by accounting for 25.6% of all class actions. However, the new filings have tended to be lower exposure, so companies are not necessarily going to be facing potential bankruptcy when employees sue to collect overtime pay.

Clabby said in-house legal departments are now doing an early case assessment before responding to a class action. They are having their outside counsel do a more careful review that includes reading through the complaint and other documents, interviewing some employees and thinking about the legal arguments, then deciding how to handle the matter.

An early assessment could cost the company $50,000, but that is dwarfed by the hundreds of thousands that could be paid just to get to a motion to dismiss. More than trying to cut expenses, Clabby said the approach reflects management’s concern about employees’ wellbeing.

“We got some great feedback this year in the survey from companies that said, ‘Look, if we made a mistake, particularly in labor and employment, we want to fix it and do right by our employees,’” he said.

Positive changes

The wage and hour issues are the result of profound changes in workplaces caused by the pandemic.

Most of these kinds of claims arise under the Fair Labor Standards Act, which, as Maatman explained, was part of the New Deal legislation of the Great Depression and designed for brick-and-mortar factories and offices. However, now the workplace is digital and employees are demanding they be allowed to work remotely.

Consequently, questions are increasing about when a worker is considered to be on-the-clock. So more than ever, employers must be attentive to the way employees are paid.

Consequently, questions are increasing about when a worker is considered to be on-the-clock. So more than ever, employers must be attentive to the way employees are paid.

“If you’re an employer and you’re looking at your issues and your risks, your number one risk is how you pay people,” Maatman said. “That’s where you’re going to be sued more often than not and that’s where these class actions are going to come from.”

Benjamin Ellis of HKM Employment Attorneys in Indianapolis said he sees the changes to the workplace as creating a “kind of spirit of the age” where workers feel like they deserve better and they are more willing to take risks.

Ellis has not handled class actions, but the issues individual employees are coming to him with are different than 10 years ago. Now the workers are bringing claims related to disability accommodations, medical leave and wage and hour matters. In the past, the disputes arose from hostile work environment allegations.

While he said he expects the unsettled labor relations to continue, he also said he is noticing changes that appear to be making the employer-employee relationship better.

“There are a lot of employers that seem to be much more flexible in terms of scheduling,” Ellis said. “With remote work comes the ability to potentially work unusual hours, be more flexible for family time versus work time. And those sorts of changes, I think, do seem to have been positive.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.