Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAlmost immediately after the coronavirus reached the United States, criminal justice advocates sounded the alarm on behalf of the incarcerated. Inmates in county jails, state prisons and federal penitentiaries are at a higher risk of contracting the virus, advocates say, simply because of the nature of their living conditions.

To that end, state and local leaders have been called upon to take proactive steps to reduce jail populations. The result has been a mixed bag.

“Some states are doing more than others,” said Nicole Porter, director of advocacy with The Sentencing Project, an organization based in Washington, D.C.

In Indiana, organizations such as the state American Civil Liberties Union have publicly urged government leaders to implement compassionate release plans. Some local officials have taken steps to reduce jail populations in light of the pandemic, but Indiana has not seen a coordinated effort, said Jane Henegar, executive director of the ACLU of Indiana.

More action has been seen in the courts, where lawyers and pro se inmates have pointed to underlying health conditions as a reason to serve their sentences outside prison walls. The goal, lawyers say, is to ensure that those who are incarcerated are not placed at a greater risk of infection only because they are behind bars.

Limited resources

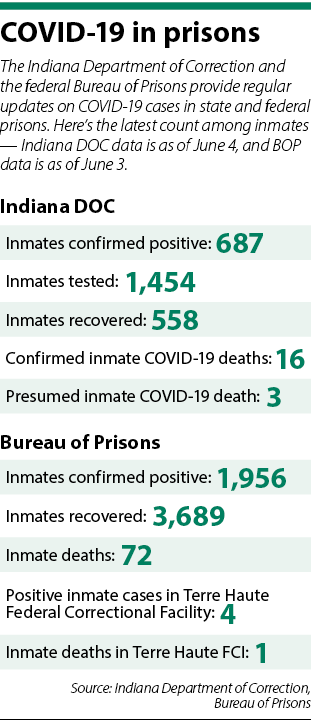

Like other government organizations, the federal Bureau of Prisons and the Indiana Department of Correction have implemented COVID-19 response plans designed to ensure inmate and staff health. Among other steps, in-person visits have been restricted in favor of virtual visits, and inmates who have tested positive for or have been exposed to the novel coronavirus are often placed in an in-facility quarantine.

But the nature of incarceration makes full adherence to guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention difficult, Henegar said. Jails and prisons are designed for close-quarters living, while staffers risk bringing the virus into a facility from the community.

“We’ve all heard a lot about how nursing home residents are vulnerable to the virus because of the way it’s spread, and there are similar factors in jail,” Henegar said. “… The way it’s designed, with people living in close proximity and staff coming in and out of the community, it endangers both populations.”

Mario Garcia, a private practitioner who is leading the Indiana Southern District’s COVID-19 compassionate release efforts, also pointed to restrictions on inmates’ access to hygiene supplies. Alcohol-based hand sanitizer, for example, is not permitted, while soap is distributed only at certain times.

Even the use of masks can be complicated, Garcia added, because inmates don’t have access to resources to keep cloth masks clean.

“It’s difficult in prison to maintain CDC guidelines,” Garcia said. “… When they line up for counts or meals, it’s literally chin to back. There’s no 6 feet of separation.”

Pretrial efforts

In the courts, lawyers are taking different approaches to seeking the release of clients whose medical conditions might increase their risk of illness from COVID-19.

In the Indiana Federal Community Defenders office, one of the first steps in the pandemic response was to review open cases and identify clients who might be medically at-risk, said Sam Ansell, an assistant federal defender in the Southern District of Indiana. Once identified, Ansell began filing pretrial release motions for those clients.

Using the federal detention statute, Ansell has argued COVID-19 and its related risks have created a change in circumstances and a compelling reason for his clients’ temporary release. He’s had the most success when a client has an underlying respiratory illness, but vascular ailments such as high blood pressure have been less successful.

That difference is likely due to the fact that COVID-19 is largely seen as attacking the lungs, Ansell opined. But, he added, new research indicates there is also a “vascular phase” of the virus that can attack blood vessels.

Whatever the medical reason, Ansell’s goal has been to enable at-risk defendants to self-isolate outside of prison walls, where they can maintain better hygiene habits and control over who they interact with.

“I think what is dangerous about this virus is that we know that asymptomatic carriers are a major vector of transmission,” he said. “Without widespread testing, I don’t think measures such as temperature checks and testing people who are already symptomatic is adequate to stop the spread of the virus.”

Compassionate release

Garcia’s work in the Indiana Southern District Court has focused on inmates seeking compassionate release from their sentences. He’s working with a handful of local attorneys to handle these cases during the pandemic.

One of those lawyers is Kate DiNardo, a solo practitioner in Indianapolis. The cases she and Garcia handle pursue relief under the First Step Act, a bipartisan prison reform initiative signed into law in 2018.

DiNardo’s clients, all of whom have had underlying health issues, have sought extensions of their terms of supervised release. If successful, those inmates won’t spend any additional time in the BOP, but instead will be under the conditions of supervised release until the date their sentences would expire.

In those situations, an inmate could be placed under conditions such as GPS monitoring while also being under the supervision of a federal probation officer, Garcia said.

Garcia knows the Southern District of Indiana — already one of the busiest dockets in the country — has been flooded with, in his estimate, at least 100 motions for coronavirus-related relief. And those petitions don’t just come from Indiana: many inmates sentenced in the Hoosier state are serving time across the country.

According to data from the Bureau of Prisons, as of June 4, the facility in Forrest City, Arkansas, has reported 471 positive cases of COVID-19 among inmates, plus one positive case among staff.

There have been no deaths in Forrest City, but it’s a different situation at the Elkton facility in Ohio, where a total of 431 inmates and staffers have tested positive and nine inmates have died.

“That’s really what’s caused this court to be very busy,” Garcia said of the Indiana Southern District.

Continued advocacy

Though the pandemic appears to be plateauing, Henegar cautioned against forgetting about the risks that inmates are facing. She and the ACLU are still calling on government leaders to act to protect the incarcerated, and lawyers are still filing release motions in court.

DiNardo, for example, was unsuccessful in her first attempt to secure release for Daryl Albertson, a client who is incarcerated in West Virginia. But her motion was denied without prejudice, so she plans to pursue it again, this time with the advantage of additional records and the exhaustion of a 30-day administrative barrier.

Some citizens have raised concerns about whether releasing inmates early, even due to COVID-19, might place the public at risk. But public risk is a factor courts must consider when deciding a motion for release, Ansell said, and the risk to the public must be weighed against the risk to an inmate’s health.

For Cooper of The Sentencing Project, the hope is that discussions of decarceration during COVID-19 will spark more discussions about general decarceration nationwide.

Henegar sees a similar opportunity to humanize those behind bars.

“People in jails and prisons are people, too,” Henegar said. “Their health should not be sacrificed because of some speculated harm they might bring to the broader community. I think we’re better than that.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.