Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhat others might dismiss as junk, Stephen Farris can repair, restore and rejuvenate with just duct tape and a screwdriver.

The electrical engineer-turned-patent agent at Ice Miller holds three patents in fuel cell technology from his days working at a General Motors facility in Honeoye Falls, New York. He has more ideas and once crafted a plan to launch a startup, but he was unable to attract investors because his innovation was not patented.

The barrier that prevented him from getting that patent is one Farris believes is linked to a common situation in his life: He is often the only Black guy in the room. In his 17-year career with GM and his seven years in the legal profession, Farris has neither worked alongside a colleague nor represented a client who is Black.

Farris’ dreams were blocked by the cost of getting a patent. And the phone calls he regularly gets from other minorities and women who want to patent their inventions tell him he is not unique. He is happy to provide nonlegal advice to callers, but when he discusses the money they will need, the conversations end.

A main reason for the high cost of getting a patent is legal fees — a problem that puzzles the always-tinkering Farris. The patent process is complex, and most people need legal assistance, but intellectual property attorneys’ charges for preparing, submitting and presenting an application before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office can swell to hundreds of thousands of dollars, he said.

“I think one of the barriers that keeps minorities away, they don’t have all this money to just spend,” Farris said. “I’m telling you, these bills go through the roof overnight.”

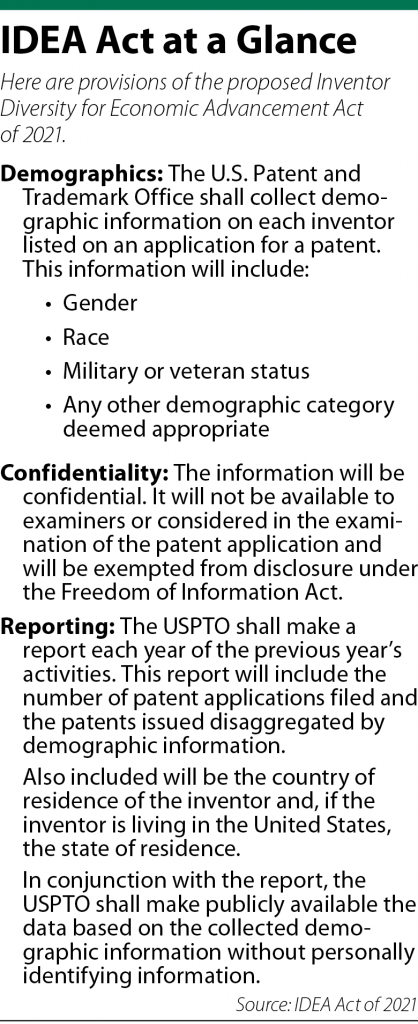

A bill introduced in the U.S. Senate in March seeks to quantify the lack of diversity among patent holders. The Inventor Diversity for Economic Advancement Act of 2021 — or IDEA Act — would require the USPTO to collect inventors’ demographic information, including race and gender.

“It’s simply good policy and good business to want to fully integrate people of all types into our innovation economy,” Sen. Mazie Hirono, D-Hawaii, told her colleagues in presenting the bill. “But if we have any hope of closing the various patent gaps, we must first get a firm grasp on the scope of the problem.”

When she did a quick analysis of her client base, Lindsey Rothrock, trademark and copyright attorney at Taft Stettinius & Hollister in Indianapolis, was surprised. Just 24% of her clients were women who either owned or co-owned a business. Among the non-owners, women comprised only 20% of the individuals who were the point of contact for the IP attorneys representing the company. Minority percentages were even lower.

Rothrock pointed out women and people of color without IP protections could be putting their businesses at risk. Having a fully registered trademark enables a company to expand into new markets while safeguarding the brand as well as the goodwill and reputation the business has carefully honed.

Rothrock is hopeful that as companies become more mindful and aware of racial and gender disparities, more women and minorities will seek and obtain patents. Just like her survey helped her see the lack of diversity in her client base, the IDEA Act has the potential to illuminate the scope of the shortfall.

“I think having that hard data in front of Congress, or whatever committee that may be put in place to assess it, would be really helpful in just seeing what gaps there are and in starting to think of ways to close those gaps,” Rothrock said.

New payment model

The IDEA Act is following a recommendation the USPTO made as part of the Study of Underrepresented Classes Chasing Engineering and Science Success, or SUCCESS Act, passed by Congress in 2018. Under the law, the patent office was required to track down publicly available data on patents issued annually to women, minorities and veterans.

In its 2019 report to Capitol Hill, the available information showed women were inventors on about 4% of patents granted in 1976, which increased to 21% by 2016. A survey of patent applications and research and development awards from 2011 to 2015 found a wide racial gap: Only 0.3% of the U.S.-born innovators were Black, 1.5% were Asian, 1.4% were Hispanic and 59.6% were white.

Farris said the lack of diversity hurts the public by decreasing the number of new products and services coming to the market.

“I think not having that diversity limits the entrepreneurship in the technology areas because the patent system inherently drives the economy,” he said. “It gives companies and individuals a reason to invent and develop new technology.”

Yet the hourly rates the market will bear prohibits many innovators, especially women and minorities, from hiring the attorneys they need to even file a patent application.

A solution Farris has mulled over is replicated upon the contingency fee model. Inventors would pay a reasonable flat fee upfront in exchange for paying the full cost once the patent is issued and the product or service is making money. Such a method would need to comprehensively include business aspects, helping innovators market, sell or license their invention.

“It would require more of a holistic approach than just getting them the patent and walking away,” Farris said.

Help beyond patents

Mark Janis, director of the Center for Intellectual Property Research at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, echoed Farris.

Janis sees the lack of diversity tied to a lack of financial support and access to patent expertise. Getting the patent requires money, but inventors also would likely need guidance to do such things as formulate a business plan, tap into capital and develop a marketing strategy.

Consequently, Janis expects improving diversity among patent-holding innovators will probably stretch beyond the USPTO. Other agencies and organizations will have to work to create equal patent opportunities for women and minorities.

“We need to reach these people because they have great inventions,” Janis said. “But they may not be people of means, so they need things like a pro bono clinic and other economic development forms of support.”

IU Maurer has initiatives to help entrepreneurs and enhance diversity. The Intellectual Property Law Clinic and the PatentConnect program draw upon law students and practicing attorneys to offer pro bono legal assistance to inventors. Janis and his team also have been discussing ways to diversify the pool of patent holders by reaching out to minority communities and encouraging innovators.

“I think we’re going to have to be satisfied with retail-level advancements, person by person and hope that culminates in making a difference,” Janis said.

The legal profession might exemplify how to improve diversity in the innovation community.

Julia Spoor Gard, chair of the IP department at Barnes & Thornburg, has seen more women attorneys entering the practice area in the last 20 years. Thoughtful fostering and support of female attorneys has benefited the profession and clients.

Likewise, she credited firms’ diversity and inclusion efforts. Women and minority attorneys have been part of the conversation, being asked about the challenges they face and the support they need.

Gard maintains better ideas are the rewards of diversity.

“I’m a big believer in the marketplace of ideas,” she said. “I think we should be talking about things. Everything is on the table, and let’s get everybody’s point of view. I just don’t think you can go wrong with more ideas and more communication.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.