Subscriber Benefit

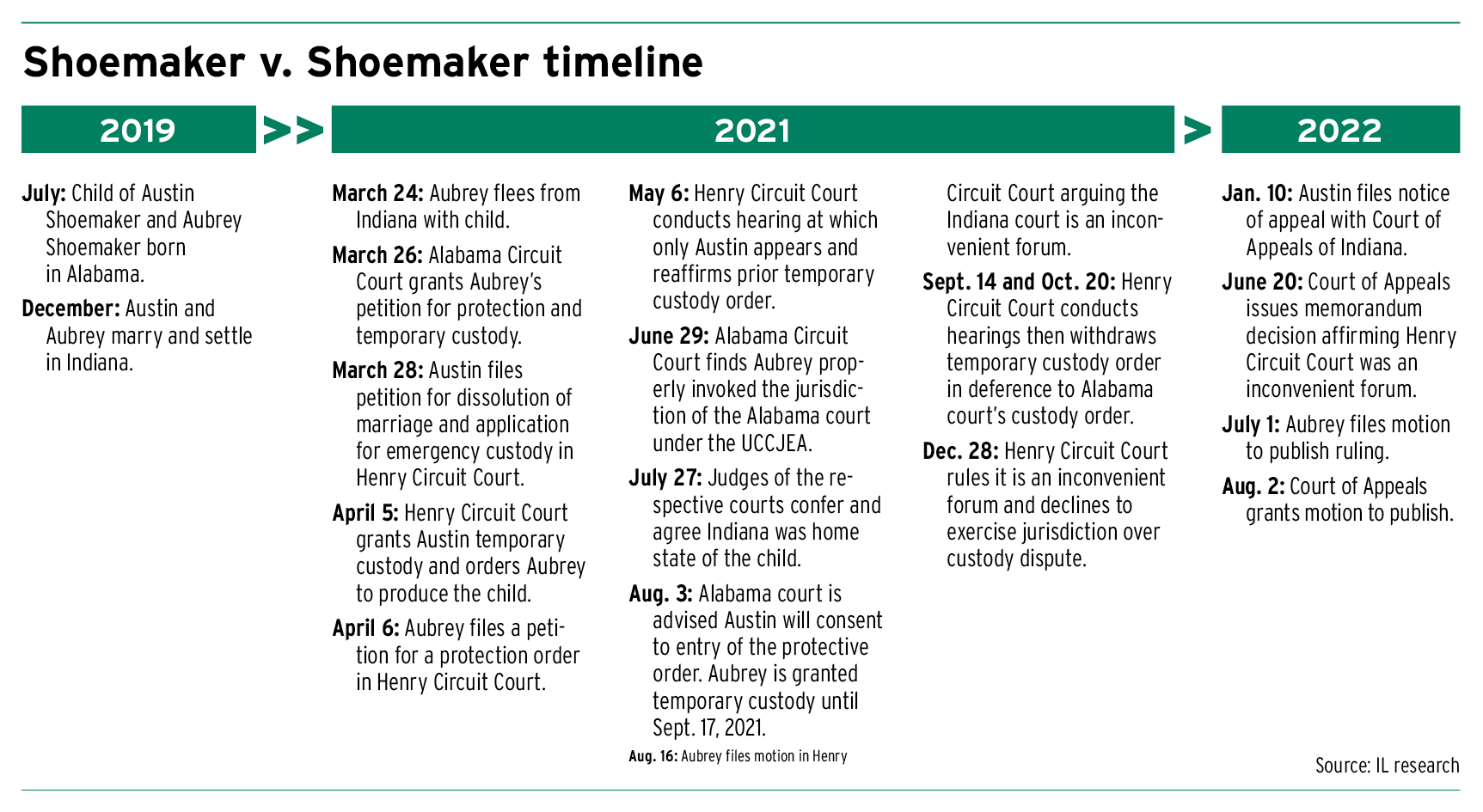

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn March of 2021, Aubrey Shoemaker grabbed her child and fled from Indiana to the safety of her family in Alabama.

The next day, she walked into an Alabama courthouse and filed a petition for an order of protection against her husband, Austin Shoemaker. Three days later, Austin filed for divorce and emergency custody of his child in Henry Circuit Court.

Thus started a fight that initially involved two trial courts in different states issuing conflicting orders. Aubrey and Austin were each granted custody by the Alabama court and the Indiana court, respectively.

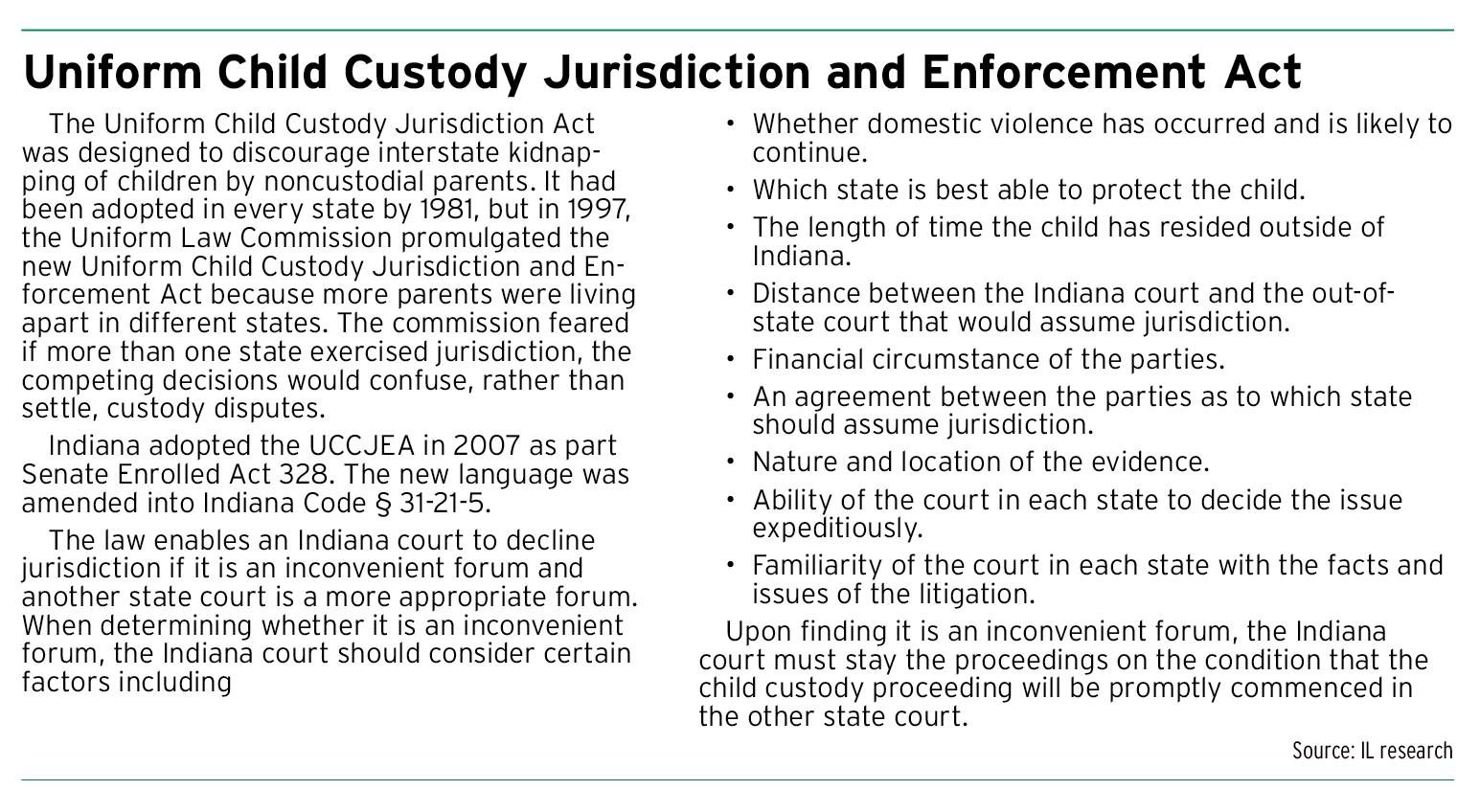

Because of the dueling courts, the case invoked the Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction and Enforcement Act, and even though Indiana was designated as the home state, the proceedings were eventually turned over to the Alabama court. The Henry Circuit Court determined it was an “inconvenient forum” under the UCCJEA because of Aubrey’s allegations and evidence of abuse.

This summer, the Court of Appeals of Indiana affirmed the trial court’s ruling in a case of first impression that attorneys say created good caselaw for survivors of domestic violence.

“This is exactly what the UCCJEA is intended to do,” Kerry Hyatt Bennett, chief legal counsel of the Indiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence, said. “If you can successfully make the argument that staying in a certain jurisdiction is a credible danger to a person or a person’s child, you should have the right to be able to leave that jurisdiction.”

However, Anthony Saunders, a New Castle attorney who represented Austin in Henry Circuit Court, said he believes the ruling shows the Indiana General Assembly needs to amend the statute. The UCCJEA lists several factors that a court must consider when deciding if it is an inconvenient forum but, Saunders said, Henry Circuit based its decision on a single factor: domestic violence had occurred and was likely to continue.

Saunders said following that lead, anyone could flee to another state, claim domestic violence and get jurisdiction transferred. That is counter to the UCCJEA’s original intent of preventing noncustodial parents from abducting their children, he said.

“If all you need is that one factor, then that’s what the Legislature should have said but they didn’t,” Saunders said. “… (Legislators) need to do something to just say that domestic violence is not the sole factor that a court can rely on to determine if it is an inconvenient forum.”

Recorded proof

The case, Austin Shoemaker v. Aubrey Shoemaker, 22A-DC-50, pivoted on two key elements: lawyers and evidence.

Unlike many survivors of domestic violence, Aubrey — who alleged she had been physically abused and threatened by her husband — had legal representation provided by the Indiana Coalition Against Domestic Violence at the trial and appellate levels. Also, she had photos of her injuries and recordings of her husband’s verbal abuse, including his assertion that his family is in the mafia and “they will take you out to the f—ing dump and they will bury you, alive or dead.”

The evidence was presented in the Henry Circuit Court at the two-day hearing over the inconvenient forum question. According to Matt Albaugh, partner at Taft Stettinius & Hollister in Indianapolis who represented Aubrey before the Court of Appeals, Austin testified and had his family and friends testify at the hearing while Aubrey could offer only her own testimony. But the photos, recordings and text messages that she had preserved prevented the case from sliding into a he-said-she-said dispute.

Especially important were the audio recordings.

“The Court of Appeals could actually hear his threats,” Albaugh said. “The Court of Appeals with its own ears could hear his words and the things that he was saying to her. … This is another reason why this was sort of the right case to take to the Court of Appeals to get the opinion that we wanted to get.”

Saunders argued in his reply brief that only under “extreme circumstances” of abuse should the home state court be identified as the inconvenient forum. Such a situation would create a “paper trail of evidence” including medical records, hospital visits and convictions.

With no paper trail, Aubrey’s allegations, he said, were “flimsy” and “ridiculous.”

“What they were hanging their hat on was (Austin) had some angry, mean phone calls to her,” Saunders said. “I’m sorry, but angry, mean phone calls are not domestic violence. They’re rude. They’re impolite. But there’s just a lot of people who, when they get to the point of divorce, are angry and hateful toward each other.”

Both Hyatt Bennett and Albaugh credited Kathrine Jack, a solo practitioner in Greenfield who represented Aubrey at trial, with getting the photos and recordings into evidence and preserving the record for appeal. Jack noted even more evidence supporting the abuse was available, so she was able to pick the strongest to present at trial.

“As far as the evidence, a lot of credit on that goes to the client because she had taken pictures and she had taken the recordings,” Jack said. “Sometimes in domestic violence cases, for whatever reason, we just don’t have that.”

‘Quietly looking’

With the litigation continuing in Alabama, Saunders said Austin is facing a drive hundreds of miles long to appear in court and, with no ties to the area, had to “go through the phone book” to find an attorney in that state.

He questioned how Henry Circuit Court was deemed inconvenient when Aubrey was allowed to appear for the hearings remotely. Hyatt Bennett and Jack countered that granting jurisdiction to Alabama enables Aubrey to benefit from the support of her family and retain her job. Moreover, as matters like child support and parenting time arise, she will not have to leave the Cotton State.

“This is important for survivors that must flee a jurisdiction where they have no support and are not safe,” Hyatt Bennett said. “Abusers use the system to continue to harass and manipulate their survivors even after the legal relationship ends. If they have the resources, they would constantly be filing actions and taking them back to court.”

Hyatt Bennett first learned of this case when Aubrey’s Alabama legal aid attorney called.

The Shoemaker dispute was at the intersection of Indiana statute and domestic violence for which “there’s a staggering lack of caselaw,” Hyatt Bennett said. She had been “quietly looking” for a UCCJEA case involving domestic violence that could be used to set precedent.

Yet, the opinion issued by the Court of Appeals in June was a memorandum decision, which barred it from being cited in future cases. Hyatt Bennett and Albaugh conferred with Aubrey and got her permission to file a motion to publish, even though that carried the risk of the case being transferred to the Indiana Supreme Court.

“This case has been a long and traumatic road for me,” Aubrey said in an email. “But I have found myself, found strength and persevered through it. Without Kerry, Matt and Kathrine, I couldn’t have gotten through it. To help them and other lawyers help women and children in mine and my child’s situation, I agreed for it to be published. If publishing could help even just one victim out of the situation I was in, I would be forever grateful.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.