Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

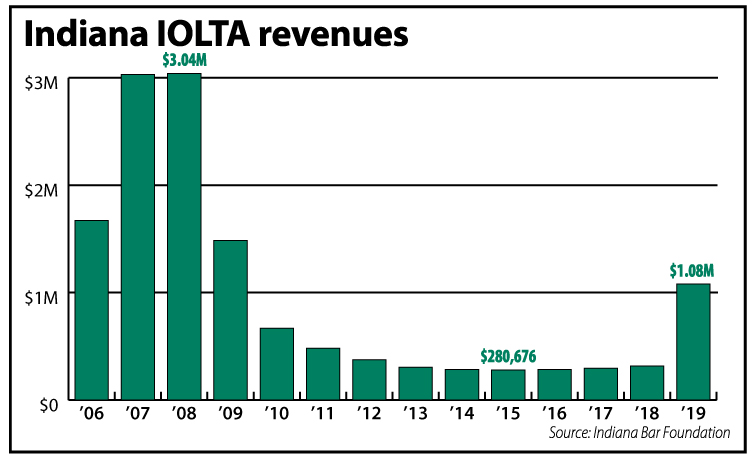

The conversation about civil legal aid in Indiana is still focused on money, but for the first time in nearly a decade, the talk is of dollars increasing rather than dwindling.

Revenues from the Interest on Lawyers Trust Accounts are ballooning past the $1 million mark for the first time since 2009. Also, the Indiana Supreme Court is preparing to offer $250,000 to create a new source of legal aid grants, and the Indiana Bar Foundation is shifting $115,000 to the Mortgage Foreclosure Program. In addition, the extra $1 that has been added to court filing fees to support civil legal aid programs continues to bring in $300,000 to $400,000 annually.

“We’ve been in the desert for so long,” said Charles Dunlap, executive director of the Indiana Bar Foundation. “We’re finally emerging and getting out to get some of these pistons firing in the engine a little bit more.”

However, no one is getting comfortable.

IOLTA, which benefited from rising interest rates, felt the ground shift a little when the Federal Reserve lowered the interest rate July 31. Also, the Indiana General Assembly turned down the Supreme Court’s request that the state’s budget raise the per-year appropriation to the Indiana Civil Legal Aid Fund from $1.5 million to $2 million.

Moreover, legal aid providers are having to devote more time and resources to applying for grants and soliciting private donations.

In ramping up its quest for private dollars, Indiana Legal Services Inc. is being thoughtful. Executive director Jon Laramore said the agency looks for grants that can support its current programs rather than creating new initiatives solely because grant money is available.

But about 60 percent of ILS’ budget is still drawn from the public money available through the Legal Services Corp. That agency has seen a boom in funding, with Congress adding a total of $30 million during the last two budget cycles and the House this year approving a $135 million increase. Although the final appropriation has been below the $550 million-plus LSC has been asking for, it is much better than the White House’s proposal to defund the organization altogether.

ILS has been growing revenue from private sources at the same time it has been receiving boosts from LSC. In the last four years, the Indianapolis-based nonprofit has increased its budget from about $9 million to $11.3 million.

Laramore said the organization is holding back about 12 percent in reserves, but the message from the board is to spend the money on delivering legal assistance to people in need.

“I’m optimistic that our funding will continue to grow,” he said. “I think we will continue to make a strong case for how much need there is for our services.”

Public and private dollars

The Legal Aid Society of Evansville underscores the importance of public money to stability.

Incorporated in 1958, the Evansville provider is included in the Vanderburgh County budget and has received the bulk of its funding, currently a little over $400,000 each year, from local government. Another $55,000 has come from United Way of Southwestern Indiana, and just over $9,600 flows from the Civil Legal Aid Fund annually.

The office has three full-time attorneys and handles about 600 new cases annually, a majority of which are in family law. Not having to chase private dollars brings a benefit, according to executive director Kevin Gibson.

“I’m sure it gives us much more time to represent clients,” Gibson said, noting his attorneys make more than 2,000 appearances in court each year. “There’s never an end to low-income people needing help.”

To get nonpublic dollars, legal aid providers are having to work harder. Indiana Landmarks President Marsh Davis said the competition for donations from individuals is fierce. The fight is being driven largely by state and federal governments pulling back their traditional support, which has resulted in institutions like public libraries and public universities having to seek private contributions.

Davis’ organization was able to access some grant money from the Indiana Bar Foundation by partnering with Indianapolis Legal Aid Society. The two nonprofits are working jointly on a housing program, with Landmarks supporting the development of new homes and ILAS providing legal assistance to the residents.

Davis’ organization was able to access some grant money from the Indiana Bar Foundation by partnering with Indianapolis Legal Aid Society. The two nonprofits are working jointly on a housing program, with Landmarks supporting the development of new homes and ILAS providing legal assistance to the residents.

More and more grant makers want nonprofits to partner, which can create some obstacles, ILAS general counsel John Floreancig said. While the collaboration with Landmarks has worked very well, not all partnerships are a good fit, and they can struggle to serve the designated need.

Complicating the situation is that grants tend to target specific problems or issues, Floreancig continued. This can hinder legal aid providers’ ability to help whoever walks through the door, because the grant requirements could limit which matters the attorneys can address.

ILAS has had to rely more on grants and donations in the past seven years. Its primary funding source, United Way of Central Indiana, dropped from providing half of the society’s annual operating dollars to contributing less than 20 percent. ILAS now has staff focused on fundraising and tracking the data that many grants now demand.

Floreancig fears the purpose of legal aid may be getting lost in the details.

“I worry we’re too concerned about numbers and not concerned enough about the people we serve,” he said. “We have to show what we’re doing in the county and show we are good stewards of the money, but when you start looking at all the metrics, you get to a point where you’re spending all your time and money on registering data that could be used to help clients.”

Sustained need

After the Legislature did not add more money to the Civil Legal Aid Fund, Indiana Chief Justice Loretta Rush did two things: she led the court’s belt tightening to find money within its own budget to divert to legal aid, and she made plans to renew her request during the next budget cycle.

“I strongly respect the separation of powers,” Rush said, explaining she does not begrudge the General Assembly for its rejection of the budget ask. “I don’t hold the purse, but I am persistent.”

The $250,000 coming from the court will be directed into high-impact grants targeting programs and proposals for medical-legal partnerships and veterans’ issues. As that money arrives, the bar foundation is estimating revenues from IOLTA and the $1 civil legal filing fees will hit $2 million in fiscal year 2020, even if the Fed cuts the rate again.

In fact, the healthy revenue stream led the foundation to leap ahead of its traditional fall grant cycle. It started pushing out $200,000 in IOLTA funds to legal aid providers in July.

Even so, the extra funding will not cover the need.

A 2019 study by Indiana University and the Coalition for Court Access found one in four civil cases filed in Indiana in 2016 involved unrepresented litigants. Also, of the people seeking help next year, the state’s legal aid providers will only have resources to fully serve 3 out of every 10 persons.

Along with putting some money into reserves, the bar foundation is looking for ways to stretch dollars. It is helping with an effort to consolidate the administrative functions of the pro bono districts, and it is examining ways to streamline the grant application process.

“I think the overall goal for this is using limited resources in the best way we can,” Dunlap said. “It’s efficiency. It’s also gathering data to direct resources to emerging trends and areas that need support.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.