Subscriber Benefit

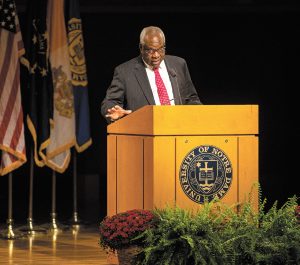

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowUnited States Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas is known for keeping mum while on the bench. But at a public lecture this month at the University of Notre Dame, the court’s longest-serving justice opened up about his life’s history and his views on the current state of the judiciary.

Thomas delivered the 2021 Tocqueville Lecture, sponsored by the Notre Dame Center for Citizenship and Constitutional Government. The justice also held private meetings at Notre Dame Law with small, invited groups.

In his lecture, Thomas discussed his childhood in Jim Crow Georgia in the 1950s, the impact of his Catholic upbringing on his worldview and the effect of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on that worldview.

After spending his young adulthood “disillusioned” by the inequality he witnessed in America, Thomas said he eventually returned to the overarching principle he was taught as a child by the nuns at his parochial school and by his grandparents: All humans are of equal worth by virtue of being children of God, and Americans — including Black Americans — have a duty to support their country while striving to improve its shortcomings.

While the audience showed overwhelming support for Thomas, a small group of protestors were present, holding signs that read, “I still believe Anita Hill.” Hill is the lawyer who publicly accused Thomas of sexual harassment.

The protestors received boos from the crowd and were escorted out of the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center on the Notre Dame campus. When they left, the crowd gave Thomas a standing ovation — his third of four.

When the uproar died down, Thomas answered a series of audience questions. The queries ranged from his Catholic faith to his views on the federalists to his concerns about the federal judiciary.

Asked about the “threats” to the judiciary he foresees over the next two decades, the justice spoke of the “difficulties of judges going beyond what Article III requires and staying within the limitations on judges.”

Answering a related question, Thomas said he likely would have more closely aligned with the anti-federalists than the federalists during the founding era. Some of the realities of American life today, he said, are things that concerned the anti-federalists.

For example, the anti-federalists were concerned about the expansion of the commerce clause and, more generally, the expansion of the power of the national government. The justice lamented the expansion of the role of the court through the incorporation doctrine via the 14th Amendment, as well as the development of substantive due process.

“Other branches (are) going into areas that are somewhat attenuated from the limited powers they’re supposed to have, the enumerated powers,” he said.

But, the justice continued, there are also misconceptions about the court’s role in American democracy. He criticized the media and advocacy groups for perpetuating the idea that jurists make “policy” based on their personal preferences.

He pointed to his own confirmation to the high court in 1991, which he described as “craziness.” In addition to the fallout from the Hill allegations, his confirmation was highly political, as Democratic senators raised concerns that he would promote conservative beliefs on the court.

Specifically, Thomas said, the issue was his stance on abortion — an issue he said he had “not thought deeply about at the time.” Even so, he said, the concern was that he would become an anti-abortion activist on the court.

In a similar vein, Thomas was asked what he does when his Catholic faith conflicts with a legal question he’s deciding. The justice said he’s never really encountered that situation, but if he did come across a legal issue that he “fundamentally” thought was wrong, he would “go and do something else.”

“I said that early on, and I still believe that,” Thomas said. “I have lived up to my oath.”

Moving away from his faith, Thomas said there are legal issues that conflict “very strongly” with his personal opinions and policy preferences, and some cases have broken his heart. Those situations were difficult early in his judicial career, he said, but he recalled the advice he received from Judge Laurence Silberman during his days on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.

“Before you sit on a case, ask yourself this question: ‘What is my role in this case as a judge?’” Thomas recalled Silberman saying. “Not as a citizen, not as a Catholic — what is my role in this case as a judge? That is a hard one, because if you stay in that lane, there are some things that you as a citizen or you as a personal preference would want to come out a different way. And that’s what I’ve tried to do.”

Carrying that philosophy with him through the years, Thomas said he now shares similar advice with his law clerks. When new clerks arrive, he encourages them to watch his actions and follow suit.

“I tell my clerks, ‘You watch me for a full year, and my job is that you leave here with clean hands, clean hearts and clear consciences. We will never do anything that’s improper,’” he said. “… In 30 terms, I don’t think a single clerk will ever tell you we have done anything other than our job.”

Even so, Thomas continued, he knows there’s a perception that judges will rule based on their political preferences. He said the American people often view judges as they do sports referees.

“If the outcome is what I want it to be, excellent work, another Marbury v. Madison,” the justice quipped. “If it is against what you are for — Dred Scott all over again.”

Scores of students attended the lecture and reflected on Thomas’ words.

One such student was Maggie Murray, a junior at Notre Dame studying history and film who hopes to enroll in law school after she graduates from undergrad. She specifically wants to pursue a career in constitutional law.

Murray said Thomas’ address was “fantastic,” particularly his discussion of how the Declaration of Independence was drafted and should be interpreted. She said it was “refreshing” to hear a high-ranking federal official espouse views that aligned with her own views as a Catholic.

Stephen Evensen, a recent Notre Dame graduate, noted that the U.S. Supreme Court has been in the news recently as the justices grapple with abortion and consider a case that some say could undermine the landmark abortion case Roe v. Wade. Evensen said he was “intrigued” by Thomas’ views on the public perception of the high court.

“So when you often read news stories about the court, it’ll say something like, ‘Supreme Court overturns this,’ ‘Supreme Court gives rights to this group, takes away rights from that group,’” Evensen said. “If you just took out the words ‘Supreme Court’ and entered ‘Congress’ or ‘Senate’ or ‘House’ or ‘presidency,’ it would look the same, despite the fact that the role of the court is so clearly very different than those other branches of the federal government, which are representative in nature, unlike the court.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.