Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAs the national conversation around student loan debt continues, and as the U.S. Supreme Court considers the Biden administration’s plan to forgive billions in student loan debt, law students are seeing their student loan debt rise.

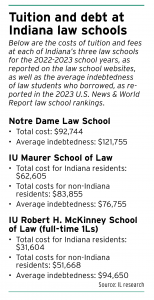

A 2020 survey from the American Bar Association found that the average debt for law school graduates had risen to more than $150,000, with 95% of survey respondents saying they had borrowed money to fund their legal education.

Paul Leopold, director of financial aid at the Indiana University Maurer School of Law, offered a lower, but still significant, number for his school: an average of $90,000 in law school debt. Against that backdrop, Indiana’s law schools are taking steps to help their students handle their debt post-graduation.

Endowment opportunity

At Notre Dame Law School, supporting graduates in their student debt journeys means making changes to its Loan Repayment Assistance Program, an endowment-funded program designed to financially support alumni pursuing public interest careers.

Previously, the program, known as LRAP, covered salaries as high as $70,000. But under changes slated to take effect in 2024, that cap will be raised to $100,000, with upward adjustments for people with children.

The other new element coming to LRAP in 2024 is that it will work in tandem for the federal Public Service Loan Forgiveness program.

Under the revised LRAP, participating graduates will enroll in an income-based federal loan repayment plan that qualifies for Public Service Loan Forgiveness. Graduates will make “modest” monthly payments under those plans, with LRAP providing funds to cover the monthly payments up to an annual cap.

After working in public interest law or public service for 10 years, participating NDLS graduates will qualify for full forgiveness of their outstanding federal loan balances. Graduates are eligible to receive LRAP assistance for 10 calendar years after beginning qualifying employment, even if they did not begin their careers in public interest work.

Bob Jones, associate dean for experiential programs and clinical professor of law at Notre Dame Law, said the goal of the revisions is to lower loan payments even more for graduates.

“We’d like to be able to cover everything, but we think we are in a very good position for now, a very good foundation to work from,” Jones said.

The program has been boosted by a hefty, multimillion dollar endowment.

“Various donors have donated millions of dollars,” Jones explained. “It’s a multimillion-dollar endowment that supports this program, and we’re continuing to grow that to where we want to make this program better and better over time.”

Salary considerations

Another goal of LRAP, Jones added, is to draw more students toward public interest careers.

“The more tangibly we can support public interest careers, the more students we’re going to attract who are interested in that career path,” he said.

A common barrier that keeps students from pursuing careers in public interest law is a lower salary compared to what could be made in private practice.

A 2022 report from the National Association for Law Placement found that the entry-level salary for an attorney at a public interest organization was $63,000. For attorneys with 11-15 years of experience, that average salary rises to $95,000 — still markedly less than first-year associate salaries at BigLaw firms.

“I want every one of our students to know that if their vocation is in public interest law, they can afford to pursue it,” Notre Dame Law Dean G. Marcus Cole said in a statement announcing the LRAP changes.

“I want every one of our students to know that if their vocation is in public interest law, they can afford to pursue it,” Notre Dame Law Dean G. Marcus Cole said in a statement announcing the LRAP changes.

Notre Dame Law 3L Emma Hildebrand said she always knew she wanted to work as a government attorney — but she also knows those jobs don’t pay very much.

“I think for a lot of us, including myself, who are going into public interest, we tend to kind of question our choice and think, ‘Maybe I should consider this law firm route, even just to help pay my loans for a few years, and then I can go into public interest,’” Hildebrand said. “It’s really tough to find that balance between financial responsibility and pursuing the career and job that we really love and are really passionate about.”

Ultimately, Hildebrand has chosen to follow her dream, lining up a job with the U.S. Justice Department this fall. Her salary would’ve been just enough to put her out of the running for LRAP before the 2024 changes were announced.

“I wasn’t going to be able to receive any assistance, but it’s still that salary that’s still tough to manage to pay back my loans and live in Washington, D.C., and afford a typical lifestyle in Washington, D.C., or anything remotely close, so that was really discouraging,” she said. “So once I heard that they were going to be raising that income threshold, it was such a relief.”

Hildebrand said she and her friends who are going into public service have talked about LRAP and look forward to using it.

“I know that so many of us are very excited to take advantage of this program, and it sounds like they’re making it more and more easy and accessible for us to do just that,” she said.

Front-end assistance

While IU Maurer doesn’t have an endowment program like what’s available at Notre Dame, the Bloomington school still has options to support its graduates. Specifically, Leopold pointed to the scholarships that are made available when students enroll.

“I like to think we offer a lot of our money on the front end,” Leopold said.

IU Maurer also has programs to help graduates financially while they are studying for the bar exam and may choose not to work, and for that in-between time when they don’t know yet if they passed.

Bar Study Support Grants are available to “public interest minded students” while they are studying for the bar exam, according to IU Maurer’s website, while Bridge to Practice Fellowships “are available to eligible graduates who secure unpaid volunteer positions with public interest organizations or small firms while continuing their job search after graduation.”

IU Maurer also offers fixed tuition, which Leopold said helps students gauge how much money they need each school year.

“You can pretty much plan out your finances for the most part,” Leopold said. “I think that that does provide students with a lot better information.”

Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law in Indianapolis was unable to comment for this story. However, its website lists several scholarships that are available to both incoming and returning students.

The school’s largest scholarship is the Kennedy Law Scholar award, which covers full tuition plus an annual stipend for living expenses. The scholarship goes to two incoming students who must have at least a 3.65 undergraduate GPA and who score at least a 162 on the LSAT, in addition to successfully completing an interview process.

IU McKinney also offers merit-based aid, including the First Year Academic Achievement Awards that goes to rising second-year students.

Relief coming?

While Leopold noted that student loan debt decreased in 2020 and 2021 while students were attending classes remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic, law school debt is often coupled with undergraduate debt.

Many law school graduates — particularly those working in public interest law — may be eligible for the Biden administration’s student loan forgiveness program, which is available to individuals earning less than $125,000 or married couples earning less than $250,000.

But that plan — which offers up to $20,000 in student loan forgiveness — remains on hold and under review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The high court heard arguments in the debt relief case in February, and a decision is expected by the end of the court’s term in June.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.