Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now In the movies it seems deft — a bait-and-switch that leaves the perp blindsided. Officers send in an undercover agent to get a recording of an offender admitting to a crime, and that recording solves the case.

In the movies it seems deft — a bait-and-switch that leaves the perp blindsided. Officers send in an undercover agent to get a recording of an offender admitting to a crime, and that recording solves the case.

But in reality, wiretapping is less dramatic. While there is an element of secrecy to surveillance, law enforcement officers are deliberate and methodical. It takes months, maybe even a year or more, to get to the point where surveillance can begin, and there are numerous safeguards in place to make sure a suspect’s rights aren’t violated.

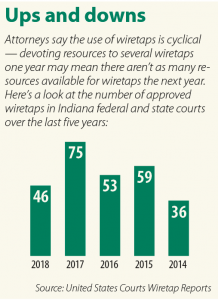

It’s because of this intense planning that prosecutors, criminal defense attorneys and law enforcement say the number of approved wiretaps was down nationwide in 2018. It’s not that fewer wiretaps are being used generally, it’s that prosecution teams have to put so much work into their wiretaps for one year, they might not have time for as many the next. The 2018 drop represents part of a cycle, they said, not a downward trend.

According to data released by the United States Courts, wiretapping in federal and state courts was down by a combined 23 percent in 2018 compared to 2017. Likewise in Indiana, federal and state courts authorized 75 wiretaps in 2017, but only 46 in 2018, according to the data.

Manpower limitations may have contributed to the 2018 decline, but Hoosier law enforcement officials say their use of wiretaps can also be limited by technological roadblocks such as encryption. But when wiretap evidence is successfully obtained, defense attorneys acknowledge cases become harder to win.

How it’s used

As a criminal defense attorney, solo practitioner Julie Treida says the majority of her wiretapping cases involve drug crimes. State and federal prosecutors agree, with Ryan Mears of the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office and Barry Glickman of the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Indiana saying their offices most commonly seek wiretap authorization for drug trafficking.

Capt. Chuck Cohen of the Indiana State Police said in his experience, wiretaps can be used for serious felonies ranging from drug crimes to murder-for-hire. Treida has also seen some white-collar cases involving a cooperating witness willing to wear a wire.

Hollywood often portrays surveillance as someone wearing a physical wire or hiding a microphone in an inconspicuous spot, such as in a pen. While the use of a hidden mic does happen, modern wiretapping also commonly involves listening in on phone calls or reading text messages.

Courts have to approve the use of surveillance, and according to Mears, Marion County’s chief trial deputy prosecutor, approval will only be given if the prosecution can point to specific phone numbers they’re interested in. When listening to those numbers, law enforcement has to be careful to only listen in on conversations that involve criminal activity, Mears said — a suspect’s conversation about a family matter is not fair game. And if a suspect gets a new phone number, the process starts over.

“That’s why we don’t do a whole lot of it, because they’re so resource-intensive that we have to make sure that when we make the decision to pursue wire surveillance that it’s the right case, that it’s going to yield the right results,” Glickman said.

‘Incredible commitment’

Getting to the right results requires substantial work on the front end for the prosecution. According to Cohen, lawyers must show courts they have pursued all other investigative methods, and any remaining methods short of surveillance would be too dangerous.

Securing that approval is a collaborative process between prosecutors and law enforcement, Mears said. In addition to determining the numbers to surveil, there are logistical questions to be answered. Will they proceed under federal or state law? How many officers will it take, and how many hours will they have to put into surveillance?

“It’s an incredible commitment,” Mears said.

On the federal level, Glickman said assistant U.S. attorneys like himself have to work through an extensive approval process before they ever take a wiretap request to court. First the application will go to a direct supervisor, then the chief of the criminal division, then the Department of Justice’s Office of Enforcement Operations before finally reaching the desk of the U.S. attorney general or a designated proxy.

Given that process, plus the manpower it takes to carry out a surveillance operation, Glickman said it could take months before prosecutors know they’ve got a case worthy of a wiretap request. But ultimately, it’s up to the courts to decide whether there’s probable cause to support the surveillance.

Fighting the evidence

All that planning comes onto Treida’s radar when a surveillance case gets to court. Defense attorneys might try to undermine wiretap evidence by challenging the probable cause for the surveillance or the process used to obtain the recording.

In Treida’s experience with drug cases, law enforcement will usually listen to 10 to 15 phones for two to three months before an indictment against 15-30 people comes down. Generally, the defendants are top-level dealers, she said, not low-level users.

As the defense attorney, Treida will seek access to the phone calls and text messages. Technology has made it easier to search through hours of recordings or thousands of pages of transcripts, she said, and government attorneys are generally helpful in pointing her toward the relevant pieces of information.

The strength of a defense case will depend on many factors, including the language a defendant uses on a recording, Treida said. Did they talk about the drugs and quantities openly, or did they use code words to mask their intentions? Prosecuting attorneys are trained to recognize code words and their meanings.

Sometimes prosecutors might take it a step further by seeking a search warrant for a suspect’s social media accounts, Treida said. It’s becoming increasingly common for drug traffickers to use social media to discuss drug sales, and she’s seen a rise in the use of Facebook, in particular, to implicate drug offenders.

Encryption issues

Encryption issues

But social media isn’t always helpful to a prosecutor’s case. Cohen of ISP noted apps such as WhatsApp, a messaging app, can actually throw up roadblocks for investigations through the use of data encryption. Even if a search warrant could be obtained for the messages someone sends through WhatsApp, current estimates show that breaking the app’s encryption software will take years, Cohen said.

Further, WhatsApp is owned by Facebook, which has already announced plans to add encryption software to Facebook Messenger and Instagram messages.

“The reality is with the ubiquity of encryption … lawful interception isn’t a possibility with encryption,” Cohen said.

Though there may be technical roadblocks, Mears said cameras and other traditional investigative techniques are still being used, and the technology backing those techniques is improving. With those improvements, Mears said prosecutors can do more with surveillance, though they remain limited by constitutional safeguards. And when a surveillance operation is successfully completed, he said the results become the “best evidence.”

“Wiretap evidence is incredibly persuasive,” Glickman agreed. “There’s nothing like the defendant’s own words played back in court to demonstrate what was going on.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.