Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhen Leon Benson walked out of prison a free man, his exoneration for murder was thanks to several people working behind the scenes on his case, including the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office Conviction Integrity Unit.

Established in 2021, the unit investigates wrongful conviction cases to determine what went wrong and how to resolve it.

Benson’s exoneration last year was the first for the team.

The unit is the first of its kind among county prosecutor offices in the state.

Co-directors Kelly Bauder and Jessica Cicchini and paralegal Danette Kennedy make up the unit’s three-person team.

Together, they sort through requests for wrongful conviction investigations to determine which ones merit further investigation.

Of the more than 500 applications the unit has received since 2021, Bauder said they’ve taken around 10 to the reinvestigation stage.

Several factors play into the decision to pursue a case further.

“It has to be a felony conviction, obviously, it has to be here in Marion County, and there has to be some kind of credible and verifiable claim of innocence or wrongful conviction,” Bauder said.

A reinvestigation can take years to complete, she explained. Benson’s case took 18 months from start to finish.

Bauder was hired to join the unit in February 2021, just a few months after Marion County Prosecutor Ryan Mears announced its creation.

In a discussion at the 2023 Community Justice Academy, Mears said the unit is necessary to make sure the right people are being held accountable for crimes.

“It’s not only about looking forward,” Mears said. “I think we have an obligation to look backwards to make sure we’re getting it right.”

Both Bauder and Cicchini are former defense attorneys, which was crucial for Mears.

“I thought it was really important that we hire defense attorneys who could come in and they can pick apart a case and they would be able to say, ‘hey, this is why we think this conviction might be unjust or these are things we need to take a better look at,’” Mears told the academy.

To get the unit off the ground, Bauder said the team spoke to several conviction integrity units across the country.

“We spent a lot of time researching the things that they did,” Bauder said. “And that took us several months to get ourselves acclimated and ready to build a unit that we thought would best fit Marion County.”

One of the goals of Marion County’s unit is to encourage collaboration within the criminal justice system. Both prosecutors and defense teams must trust each other through the reinvestigation process, offering the best tools to resolve a wrongful conviction.

“It’s very different than the traditional roles of the prosecutor and defense, which is really adversarial,” she said. “If the goal of the CIU is to pursue justice, then it shouldn’t be adversarial. It should be collaborative.”

Benson’s lawsuit against police

More than a year after Benson won exoneration, he filed a lawsuit against the City of Indianapolis and officers on the original case, claiming they framed him for the murder of Kasey Schoen in 1998 and continue to try to pin the crime on him.

Joining him in the lawsuit is Kolleen Bunch, Shoen’s sister, who claims the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department continues to frame Benson for her brother’s murder and cover up the misconduct of past officers.

The lawsuit argues no physical evidence ever linked Benson to the crime.

It also claims the defendants withheld critical evidence that could have changed the outcome of the trial, since their case wasn’t strong to begin with, according to the lawsuit.

Benson went to trial twice, his first ending in a mistrial.

Twenty-five-year-old Schoen was murdered on August 8, 1998. Around 3:30 a.m., a witness said she saw a black man standing at the passenger window of Schoen’s truck and shortly after, heard what she came to learn were gunshots.

Though some witnesses identified a different man as the killer, others identified Benson as the man who shot Schoen that night.

The area where Schoen was killed was known for drug trafficking, and despite Benson claiming he was inside an apartment complex at the time of the shooting, those he was with wouldn’t confirm his alibi.

Nearly 25 years later, an investigation by the Marion County Conviction Integrity Unit and the University of San Francisco Racial Justice Clinic found the Indianapolis Police Department (now the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department) withheld evidence that pinned the crime on someone else.

Benson was exonerated in March 2023.

Given the pending litigation between Benson and IMPD, and their involvement in the reinvestigation, members of the Conviction Integrity Unit declined to talk about the case.

City officials also have declined to discuss the pending litigation.

Exonerations in Indiana

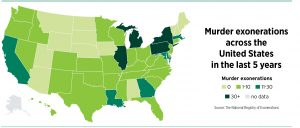

Benson’s exoneration is one of five in Marion County since 1989, according to data from the National Registry of Exonerations.

The registry, established in 2012 as a collaboration with the University of California Irvine, University of Michigan and Michigan State University, lists exonerations dating back to 1989. It also offers a more limited database of exonerations before 1989.

In total, 47 people have been exonerated in Indiana since 1989.

The data set lists several contributing factors as to why a person was wrongfully convicted in the first place. According to the registry’s data, perjury or false accusation is the leading contributing factor in wrongful convictions, with official misconduct tailing closely behind.

Perjury, misconduct, mistaken witness ID and inadequate legal defense all played a role in Benson’s conviction.

For Bauder, the end goal is always going to be justice for all.

“We look to make sure everybody has done their job correctly and that we have found the right person who committed the crime that they were charged with,” Bauder said. “And so I think it’s really important that it becomes more commonplace that people are willing to accept that all of us make mistakes, even if we were well-intended.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.