Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIt took less than a week for Indiana’s first-ever naloxone vending machine to need a restock.

On Dec. 7, Gov. Eric Holcomb announced the placement of the new, free service at the St. Joseph County Jail in South Bend.

The machine, programmed to dispense naloxone kits — which include one dose of the opioid overdose reversal drug, instructions for use and a referral to treatment for substance use disorder — was the first of at least 19 planned to open statewide, with the jails in Wayne and DuBois counties confirmed to follow suit.

In six days, the machine went from 100 doses to fewer than 10, St. Joseph County Sheriff William Redman said.

Overdose Lifeline Inc., an Indiana nonprofit dedicated to helping those affected by substance use disorder, has partnered with the Family and Social Services Administration’s Division of Mental Health and Addiction to identify jails, hospitals and other community sites interested in hosting the machines. Overdose Lifeline is purchasing the vending machines, made by Shaffer Distribution, using federal grant funds totaling $72,600 made available through DMHA.

Douglas Huntsinger, executive director for drug prevention, treatment and enforcement for the state of Indiana, said he believes the 19 machines — which can hold up to 300 naloxone kits — will all be installed by February. He said the state is just waiting for its current order to be completed. This is in addition to the 430 NaloxBoxes — which hold six to eight doses of naloxone — that Overdose Lifeline is installing in all 92 Indiana counties.

Huntsinger said there were 70,000 doses of naloxone distributed last year, and the idea for the vending machines came from Los Angeles County, California. The L.A. County Jail, one of the largest in the country, was among the first to try the vending machines in 2020 and has now distributed more than 34,000 doses of Narcan, a brand name for a device that delivers naloxone, according to the Los Angeles Times. Huntsinger said he understands Michigan has looked into the machines, but he’s unaware of any other states utilizing them.

The need for more naloxone comes as the number of overdose deaths has jumped since the start of the pandemic nationwide.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which lists Indiana as an underreported state, overdose deaths rose from 1,704 in 2019 to 2,268 in 2020. The organization also recently announced more than 100,000 Americans are now dying from overdoses annually.

“Addiction thrives in isolation,” Huntsinger said. “That’s the reason we’ve seen so many overdoses during COVID. Just as we were really starting to turn the corner, fentanyl became the primary substance found in overdose fatalities in our state. Those two factors are really driving our overdoses right now. That’s one of the reasons why it’s so important to have naloxone as available as possible because of how fatal fentanyl can be.”

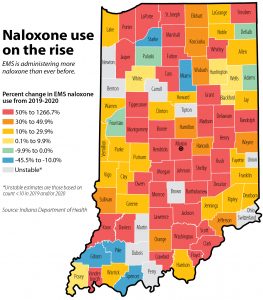

While overdose deaths have risen, so has the usage of naloxone.

While overdose deaths have risen, so has the usage of naloxone.

In a brief published in October, the Indiana Department of Health found naloxone administrations across Indiana by Emergency Medical Services were 66% higher in calendar year 2020 compared to calendar year 2019. Part of the increase, the state found, can be attributed to the fact EMS was approved to bill for naloxone on July 1, 2020.

While overdoses went up, arrests went down at the start of the pandemic. Drug arrests decreased from 74,342 offenses to 55,121 from 2019 to 2020, according to data provided by the NextLevel Recovery Indiana dashboard. The dashboard also shows the number of hospital visits for an opioid overdose jumped from 5,064 to 7,191 from 2019 to 2020.

Aaron’s Law

In 2015, Indiana Senate Enrolled 406 was signed into law by then-Gov. Mike Pence. Under the law, laypersons could access naloxone via a prescription.

SEA 406, commonly known as “Aaron’s Law, was amended in 2016 to allow individuals to access naloxone without a prescription. In addition, it offered some protections from civil and criminal charges to laypersons administering naloxone.

While some protections are offered, both the individual with naloxone and the person overdosing are not fully immune from arrest. Among the chief concerns is the lack of harm reduction provided in the law’s current form, according to Nicolas Terry, Hall Render professor of law and executive director for the Hall Center for Law and Health at the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law.

Currently, law enforcement officers can arrest an individual if they call 911 if someone has overdosed and they didn’t administer naloxone. Also, the person who administered naloxone must give the officer their full name and any relevant information they are asked for — a requirement some say is problematic if that person has also used drugs. In addition, immunity from arrest for those administering naloxone is only granted for a limited number of offenses, such as possession of cocaine, methamphetamine, a controlled substance, paraphernalia, marijuana or a synthetic drug. So if the individual has an outstanding warrant, parole violation, etc., they are subject to arrest. Individuals who have overdosed have no legal immunity.

“We need to completely reframe, reword, our Good Samaritan Act to encourage people to call for emergency treatment even though they themselves may be people who use drugs and could be in danger of arrest when law enforcement arrives,” Terry said. “We need to modify our drug paraphernalia laws, which at the moment catch harm reduction.”

Justin Phillips, executive director of Overdose Lifeline, said she is working to put more immunity into the law as it pertains to overdoses. She said one way to solve the problem, and encourage people to call for help, would be to not have police show up to overdose calls — just EMS.

Hancock County Prosecutor Brent Eaton has taken a controversial approach to addressing the overdose problem.

In 2020, right before the start of the pandemic, Eaton laid out a new policy: When Greenfield police officers respond to an overdose call, they investigate by default. During an investigation, officers can look for evidence to establish probable cause to obtain a drug test. If a person then tests positive for an illegal substance and there is paraphernalia — which could include naloxone but would also require additional evidence — the individual could be arrested for possession of a controlled substance.

The goal of the policy is to have defendants plead guilty and serve part of their sentence through probation, which would provide treatment opportunities for offenders. Eaton said there’s no “one-size-fits-all” approach to the cases, and the intent is to help save lives. He also said there’s often consent for a drug screen, so a search warrant is not necessary.

“Every community needs to make choices in what’s right for them,” Eaton said. “Every prosecutor, every law enforcement apparatus makes decisions right for them. They all must balance limited resources to try and do right by the community they represent. If we’re in a position to where we have evidence a crime has occurred, and we have reason to believe, if that crime continues to occur, someone could well meet an unnatural death, I’m going to err on the side of enforcing the law to prevent that.

“… We’re in a desperate struggle to try and do everything we can to save people,” Eaton continued. “I have gotten a lot of grief from people around the country saying … ‘Get these people treatment.’ Well, OK, I don’t have a treatment facility to send them to. I would bet there are probably 80-plus counties in Indiana that don’t have that at their fingertips. It’s not a tool we have.”

Sheriff Redman said he’s willing to answer any call from a law enforcement agency concerned about the naloxone vending machines.

“It is our job to help and save people and save lives,” he said. “I support it.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.