Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhen Lorenzo Murillo finished his undergraduate degree at Indiana University, he was glad to be done with school, but his parents encouraged him to get a J.D. As his mother reasoned, what was another three years of studying?

The Elkhart native and first in his family to go to college knew law school was more than just a few more years of coursework but, he said, “That’s super hard to explain.”

With the demands of the classroom, intensity of the clinics and race for summer positions, law schools require a lot of time and hard work. However, they also have increasingly required a lot of money.

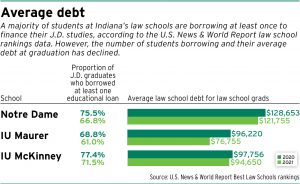

An analysis by Law School Transparency shows that average tuition at public accredited law schools was 5.92 times more expensive in 2019 than it was in 1985. Consequently, law students are taking out loans to pay for their studies, which has pushed the average amount borrowed to $118,068 in 2020.

Murillo was a 21st century scholar at IU-Bloomington, so his undergraduate tuition was covered. He was subsequently awarded an Indiana Conference for Legal Education Opportunity scholarship, which provided $27,000 over his three years at Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law, and he received other financial help including $5,000 from Taft Stettinius& Hollister.

Still, as he prepares to graduate in May, Murillo estimated he is leaving law school with between $60,000 and $70,000 in debt.

“I think everybody who attends law school has at least the hope that the J.D. and passing the bar, being an attorney will eventually outweigh whatever the upfront cost was even though it looks terrible on paper,” Murillo said.

The American Bar Association took steps earlier this year to try to help law students manage their debt. At the recommendation of the Council of the Section of Legal Education and Admissions, the House of Delegates approved new requirements that law schools provide admitted students information about financial aid and student loans, including financial counseling.

Only 12 comments were received when the change to Standard 507 was proposed. According to the council, one individual questioned the need for the new requirement because most law schools were already likely offering financial education. Another four individuals supported or had no objections to the revisions.

New lawyers say their debt burden looms over every aspect of their lives. It influences their career choices, interrupts typical rites of adulthood like buying a home and impacts their physical and mental health. Even as they love being attorneys, recent law school graduates struggle to pay off their obligation.

Josephine Bahn, member of the ABA Young Lawyers Division speaking in her own individual capacity, pointed out that even with significant scholarships, law school students can still go into debt. Their tuition may be covered but they will have to buy textbooks, which each cost hundreds of dollars, and they will have to pay for living expenses such as rent.

“I think it’s very easy for folks to say that we all should work harder and smarter, but the astronomical toll of $200,000 or $250,000 worth of education debt is something that is all-encompassing,” Bahn said, adding her debt load is not that high. “It’s not something that you can wake up and forget about.s

Salary considerations

Salary considerations

Kyle Fry, an Iowa attorney and board member of Law School Transparency, maintained that tackling the problem of student loans must involve the practicing bar as well as law schools. A key issue would be adjusting the unrealistic expectations surrounding starting salaries, Fry said.

He pointed to LST’s examination of starting pay for 2018 law school graduates. The report found only about 14% commanded an annual salary of $190,000 while the median yearly-income was $70,000.

Yet when arriving at law school, students think of themselves as high achievers and believe they will be among the elite who will get the high-paying positions in the big law firms, Fry said. The ABA and the law schools, while making the profession rewarding, should teach students that only a few will begin their careers with six-figure incomes.

“The old adage of ‘Look to your left, look to your right, one of you won’t be here in six months,’ is not true,” Fry said. “What you realize in law school is ‘You’re not all going to be able to go to work and make $150,000 out of law school.’”

Faith Welch, associate at Haller Colvin in Fort Wayne, decided on a career as a lawyer rather than a college history professor in part because her cost/benefit analysis showed she would have a better chance of getting a job and supporting herself in the legal profession.

Welch received a full scholarship to the University of Dayton School of Law but still arrived in Allen County owing about $85,000 from having to pay for textbooks, an array of student fees and living expenses. Welch began working at the prosecutor’s office, and while the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program would have erased her student loans if she had stayed for 10 years, she jumped into private practice. Doing another cost/benefit analysis, she determined she could better manage her student loan payments on a law firm salary.

Although Welch took part in the financial counseling offered at her law school, she said the program did not explain the practical implications of debt. She wishes the counseling — which she remembered as consisting of a video — had gone into detail about how that monthly loan payment would impact her ability to buy a house, a car and even choose a job.

“It’s not that I don’t love my job; I do,” Welch said. “I’m very grateful for the fact that it turned out as well as it has, but I also know how lucky I am. If it hadn’t worked out and I hated it, I’d still be doing it anyway.”

Living with debt

The Evansville Bar Association’s Young Lawyers Section recently hosted a presentation about student loan debt. Despite not offering continuing legal education credit, the event recorded “a very solid turnout,” which reinforces Jordan Saner’s belief that new lawyers are weighed down by their debt but committed to paying what they owe.

“It’s not a desire to avoid having to repay their loans,” Saner, an associate at Stoll Keenon Ogden and a leader in the Young Lawyers Section, said. “If students who are in this situation could repay their loans easily, they would absolutely do so.”

A graduate of Indiana University Maurer School of Law, Saner said he and his classmates were offered financial seminars and counseling. However, like Welch, he said understanding the true impact of debt is difficult. Moreover, law students really do not have any options to mitigate their debt because they need to take out loans to finish their law degrees.

“… Those kinds of presentations, they’re scary, they’re terrifying,” Saner said. “It’s a very scary thing to realize that you’re going to be saddled with this for the next 30 years of your life.”

In a few weeks, Murillo will be starting the next chapter of his life as he celebrates his law school graduation with his family. He has accepted an associate’s position at Taft and is planning for a monthly student loan payment of about $1,400.

Murillo credited IU McKinney with helping him get scholarships and with counseling him about his finances. Also, he highlighted the money he received from the ICLEO program as not only lowering his debt, but enabling him to become an attorney.

“The $27,000, that essentially was a full year of law school (costs) covered and I don’t think I would be here without them,” Murillo said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.