Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn the criminal justice world, indigency is a binary question: you either are, or you aren’t. But the reality is often not so black and white — just because you’re not indigent doesn’t mean you’re not hurting for money.

In the gap between people of means and people in poverty, the criminal justice system can be a difficult economic maze. You’re ordered to pay court costs, but because your financial situation is not much better than an indigent person’s, you struggle to make the payments. A default on court costs, generally about $185, can land you in jail, where you earn a small credit each day until your costs can be paid in full.

But legislation that took effect last month is providing offenders in these situations another option to offset their fees. Rather than incarceration, the new law would let people struggling to pay their court costs work off their debt through community service or volunteering.

The bill passed the Indiana Legislature with little opposition, though concerns have been raised about what the legislation might mean for court operating budgets. Supporters, however, say the measure will have a minimal fiscal impact, but a significant impact on offenders and their communities.

“It’s about options,” said Rep. Jim Pressel, the Rolling Prairie Republican who authored the bill.

Another option

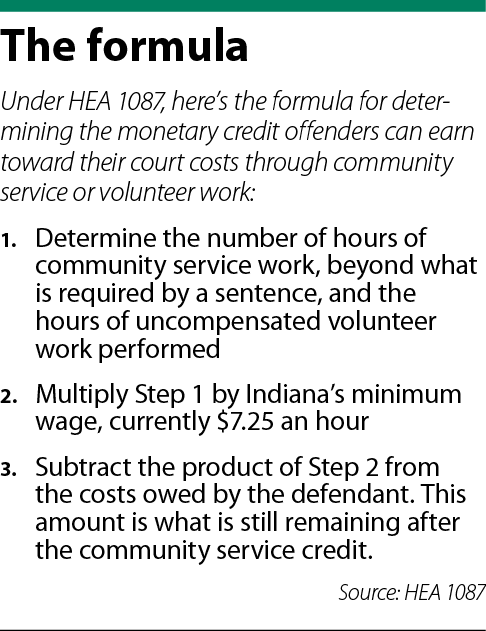

Under House Enrolled Act 1087, which took effect July 1, judges are given discretion to allow defendants to complete community service or volunteer work as an offset against court costs. The costs considered total about $185, Pressel said, and include the basic fees assessed each time a person goes to court. According to the bill’s fiscal impact statement, prepared by the Legislative Services Agency, that amount would generally include the $120 criminal costs fee under Indiana Code § 33-37-4-1(a), and nine fees under I.C. 33-37-5.

To qualify, an offender must be found to not be indigent. Qualifying work can include court-ordered community service beyond the time required by a sentence, or “regular” volunteer work performed for at least 20 hours in a 60-day period or at least two hours per week.

Pressel said the idea of the bill was brought to him by a local probation department dissatisfied with the number of people being incarcerated for failure to pay their costs. Indiana law allows offenders incarcerated for nonpayment to earn a $20-per-day credit, meaning a person would have to serve about 10 days to pay off the $185 in costs.

But it costs about $30 a day to incarcerate a person, Pressel said, plus the personal costs the person would incur through things like lost wages. In contrast, according to the LSA, an offender could eliminate their court debt with about 26 hours of community service or volunteer work.

“We want to give them an opportunity to work this off,” the lawmaker said. “We’re not locking them up, we’re saving dollars and we create, maybe, a connection with them in the community somewhere that gets them to another place in life.”

Being deliberate

Michael Moore, the assistant executive director of the Indiana Public Defender Council who testified in favor of HEA 1087 in the House, describes the bill’s target audience as the “working poor.” These are people who regularly move in and out of poverty, who are barely living within their means, or who maybe are students.

In Marion County, courts will often turn unpaid court costs into a civil judgment brought by the city or county against the offender, Moore said. The debt may be sold to a third-party company, turning it into a regular bill. Smaller counties might issue warrants for arrest, Moore said, a practice he thinks has constitutional shortcomings.

Sometimes, offenders aren’t necessarily averse to going to jail, Marion Superior Judge David Certo said. In those instances, the costs might never get paid. Such situations benefit neither the offender nor the county, Certo said. But if you can keep that offender out of jail and engage them in community activities, then both parties might benefit.

“If you order them to do community service at Goodwill, that could be valuable and that community service might end up as a job,” the judge said. “… We should be deliberate about how we use community service for good outcomes for a specific individual and a community.”

If community service leads an offender to a job, that person becomes less likely to be arrested again, Certo said. Conversely, if the offender is sent to jail for nonpayment, their family could suffer.

Fiscal impact

Final votes on HEA 1087 in the House and Senate were unanimous, but the legislation did receive some early pushback on the effect it might have on courts’ operating budgets.

Speaking in the Senate Corrections and Criminal Law Committee, Indianapolis Republican Sen. Aaron Freeman noted the criminal justice system requires money to remain operational. Expenses for items such as salaries and drug tests must be paid, and the costs assessed against offenders help pay those bills, Freeman said.

Pressel, however, told Indiana Lawyer that because his bill considers only the basic costs of going to court, the impact to court revenues will be small. LSA’s fiscal statement reached a similar conclusion, calling any potential revenue loss “minor.”

What’s more, Certo said only a small amount of those costs come back to the local community. Instead, the money is often funneled to statewide judicial initiatives, such as court technology.

But the amount of money that comes back to the local court should not drive a judge’s decision on court costs, Certo said. He noted there’s been little tracking of what percentage of costs are actually collected, so he hopes this legislation will spur such tracking to get a better sense of the fiscal impact costs have on court operations.

Future study

Democratic Sen. Karen Tallian also raised concerns about the bill in committee, questioning whether it would allow judges to force poor people to work off their debts. But the law includes “may” language that gives courts discretion, not a mandate, and Pressel said he expects lawyers to ask the judge for the community service option rather than the other way around. What’s more, the Constitution would prohibit such forced labor, the bill’s proponents noted.

Tallian also raised concerns about the definition of “indigent,” an area of law Moore agrees is not well-defined. The matter was resolved in committee by noting judges make indigency determinations daily, but Moore said the Interim Study Committee on Corrections and Criminal Code has been tasked this year with reviewing court costs assessed against indigent individuals. That discussion will hopefully lead to more clarity on matters concerning indigency, such as when it’s appropriate to appoint public defenders, he said.

With the law little more than one month old, Pressel said he has not yet heard any feedback on whether litigants are taking advantage of the change or whether courts are agreeing to the community service credit. But as a judge, Certo said it’s good to have choices for litigants of different means and different needs.

“We need to be creative about how we use sanctions in court to achieve positive goals, rather than just being punitive,” the judge said. “That’s what the Constitution commands.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.