Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowMany know about fight or flight responses. But what about freeze?

That’s another reaction often associated with sexual assaults that many aren’t familiar with. Unwanted attacks or harassment can leave victims unable to respond to what’s happening to them and express that they want the attack to stop.

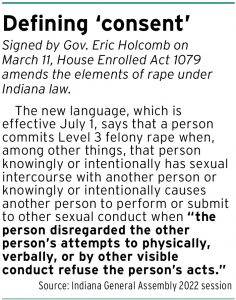

A new change expanding Indiana’s more than 200-year-old rape statute has garnered praise from advocates of sexual assault survivors and prosecutors alike for spelling out different ways that “no means no.” But even some proponents of the change say the law still lacks an explicit definition of “consent.”

Out of date

Indiana hasn’t amended its rape laws since the 1800s, according to Indiana State Rep. Sharon Negele, R-Attica.

The lawmaker, joined by Rep. Sue Errington, D-Muncie, and Rep. Donna Schaibley, R-Carmel, sought to close what Negele called a “legal loophole” by seeking to define “consent.”

Those efforts were stunted last year when Republican Sen. Mike Young, chair of the Senate Corrections and Criminal Law Committee and an attorney, declined to give the measure a vote.

But Negele’s efforts were more fruitful during the 2022 legislative session, with both the Indiana House and Senate nearly unanimously voting to pass House Enrolled Act 1079.

Under existing Indiana law, a person commits Level 3 felony rape in one of three ways:

• The other individual is compelled by force or imminent threat of force.

• The other individual is unaware that the sexual intercourse or conduct is occurring.

• The other individual is so mentally disabled or deficient that consent cannot be given.

Negele’s bill adds one more element to the list, clarifying that someone commits rape if “the person disregarded the other person’s attempts to physically, verbally, or by other visible conduct refuse the person’s acts.”

That can include a victim turning their face away, pulling up their clothes or verbally saying, “Stop.”

Proponents say the new language makes Indiana’s rape statute more “black and white” and can help prosecutors bring more cases against perpetrators.

Proponents say the new language makes Indiana’s rape statute more “black and white” and can help prosecutors bring more cases against perpetrators.

Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb signed the measure into law on March 11, allowing it to go into effect on July 1. But some say the amended law still falls short on other key points, like rape by fraud.

Rape by fraud refers to a rape in which the perpetrator obtains the victim’s agreement to engage in sexual intercourse or other sex acts, but gains it by deception. An Indiana case with those circumstances gained national attention in 2017 when a Purdue University student who had been sleeping in her boyfriend’s room had sex with a man in the bed whom she thought was her boyfriend. Instead, it was one of his friends.

That issue was originally addressed in HEA 1079 but was removed when Negele faced resistance from lawmakers about the likelihood of rape by fraud scenarios.

The new language also only implies what consent means, Negele said. It doesn’t define consent outright, which frustrates some advocates.

“We changed up the language without using the word ‘consent,’ but basically describe consent,” Negele said. “For whatever reason, using that word was troublesome to (Sen. Young).”

Young was unavailable to comment on the issue by Indiana Lawyer deadline.

Still, Negele said she is happy with the final language that was passed because it does what she was trying to accomplish. In her view, the law now describes that a lack of permission can be verbally or visibly expressed and creates a standard for jury instructions that is “crystal clear.”

Defining consent

The Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Counsel has supported the change from beginning to end, saying it can be difficult to prosecute rape cases without a legal definition of consent on the books.

“It’s far cleaner and simpler, and will provide more accountability,” said Amy Blackett, IPAC’s domestic violence and sexual assault resource prosecutor. “This certainly is going to help prosecutors, giving them another tool in their arsenal, another way that they can charge these cases.”

Blackett said there could be an infinite number of reasons why a prosecutor may decide not to file a case against a perpetrator. For example, juries often get hung up on the concept of “force or threat of force.” The amended law would eliminate several hours of explaining that issue, she said.

Blackett also said having only three subsections under the law to choose from when trying to bring a rape case limited prosecutors’ ability to successfully file those cases.

“What was unfortunately happening before, where you’d have people who would say, ‘Hey, I was raped. Why can’t we file this case?’ Well, you know, it’s because we don’t get to decide what the law is,” she said. “The law is already here. And we have to just decide whether the facts fit that or not.”

Beth White, president and CEO of the Indiana Coalition to End Sexual Assault and Human Trafficking, said that while the amended law isn’t everything she’d hoped for, it’s progress for survivors.

“The way the state law was configured, we know that it was sometimes an impediment to successful prosecution,” White said. “We are a state that doesn’t define consent. Other states have done this. This is not a radical concept.”

White said she doesn’t know how often survivors seeking help from the coalition are unable to prosecute their cases because of the way the previous rape statute was written. But according to the coalition, one in five Hoosier women will be sexually assaulted in their lifetimes.

However, 85% of sexual assault cases go unreported, White said. Indiana also ranks fourth highest in the nation for reported rapes among high school girls.

“That is terrifying and unacceptable,” she said. “It isn’t something we have to accept. It is not a foregone conclusion.”

‘False hope’

Opponents of the measure say the new language simply adds a fourth type of rape but will not have any teeth in court.

“We just don’t think that the law needs change to deal with what they said they’re attempting to do,” said Michael Moore of the Indiana Public Defender Council.

Moore predicted that there will be a flood of litigation concerning what the new language means and what the state will have to prove in rape cases. He also said there’s a possibility of ambiguous application.

For example, he posed the scenario of a perpetrator being charged with rape under subsections 1 and 4 of the statute. The survivor could argue that they refused the sexual advancements visibly, audibly or in some other way, but the perpetrator used force to overcome them.

“Then you are really kind of right back to where the law is already,” Moore said. “It didn’t change anything.”

Bloomington defense attorney Katharine “Kitty” Liell of Liell & McNeil Attorneys said the new law adds more problems than it solves.

“I don’t see it doing anything to protect survivors,” Liell opined. “In fact, I think it’s going to give them false hope that there’s some new statute that’s going to protect them, when in fact the vagueness and the inherent subjectivity, I think, will lead prosecutors to run away from that subsection as fast as possible.”

Liell, who represents individuals accused of sex crimes and handles Title IX cases at Indiana universities, said the new law is too ambiguous.

“Our law has said, ‘These are instances of nonconsensual conduct that we are going to hold people accountable for,’” she said. “And this attempt to define consent with a negative is just not going to help anything.”

“I think like a lot of changes in statute, we’ll have to see whether there are unintended consequences,” White countered. “I don’t believe there will be, but our mission here is to help survivors. I cannot see a downside, just to be quite frank.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.