Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowHaving watched people become intimidated and fearful as they try to represent themselves in court while struggling to understand legal system, Leigh Carpenter jumped at the chance to join what she sees as providing much-needed help.

Carpenter is the supervisor for Marion Superior Court’s Legal Resource Center. Occupying a converted courtroom on the fourth floor of the new courthouse at the Community Justice Campus, the center offers anyone who is unrepresented, regardless of income, access to computers, court forms, answers to general questions and, maybe most importantly, a sympathetic ear.

“Oftentimes, they just want to talk, they just want to tell you what happened,” Carpenter said. “And after they’ve had the chance to do that, they feel a lot better. We get them connected with resources that can help them and oftentimes people leave … in a better headspace than they were when they came in.”

From its opening June 1, 2022, through the end of December, the LRC recorded nearly 3,000 visits.

The center is staffed by three paid legal navigators, nonlawyers who are specially trained and provide legal information to the visitors.

Marion Superior Judge Alicia Gooden said the LRC was started on the premise that “every single person deserves access to justice.” The use of navigators is touted as a cost-effective way to provide legal help to those who either cannot afford or do not want an attorney.

“It’s a matter of time and financial resources,” Gooden said. “(The courts) felt going in the direction of having a court staff navigator was something that we could feasibly afford but also provide a service and connection.”

Marion County is not alone. Nonlawyers are also being used at the help desks in other Indiana trial courts, and with the 120 computerized kiosks installed across the state that provide access to self-help forms and IndianaLegalHelp.org.

In Evansville, a help desk is available in the William H. Miller Law Library in the court building. The desk, which gets assistance from the librarian, a navigator, volunteer attorneys and a kiosk, offers answers to individuals and through legal clinics.

Still, Scott Wylie, executive director of Pro Bono Indiana, said all that help is not enough. More vehicles for maneuvering the legal system are needed, especially for the middle class who cannot afford a $400-an-hour attorney but make too much to qualify for legal aid.

However, new methods for giving legal help typically raise concerns among lawyers. Wylie pointed out that historically, the legal profession has pushed back on efforts to expand the practice of law, whether through the opening of legal aid offices or allowing law students to serve as certified law clerks. He said he believes data now being collected will be essential in addressing the attorneys’ fears regarding the impact on legal ethics or the practice of law in general.

Through his work at the help desk, he has seen the public’s reaction.

“There’s great gratitude because we are often the first people who have offered them any help,” Wylie said. He noted that the assistance also calms a lot of the aggravation that comes when pro se litigants go into court. “People have common-sense beliefs that conflict with evidence and legal rules, making them feel unheard and frustrated.”

Differing levels of expertise

The navigators are limited to only giving legal information and cannot provide legal advice. As Carpenter explained, talking particulars of a case, discussing potential strategies or suggesting exhibits to present in court are the kinds of topics her staff is prohibited from explaining.

When visitors arrive, the navigators offer information from how to initiate a case to working through a court form and getting connected to Indiana’s online legal help portal. Sometimes, Carpenter said, the help may be as simple as explaining the difference between a plaintiff and a defendant.

While Indiana is training navigators, a handful of states are developing limited legal licensing programs. The licensed professionals are not attorneys, but they can offer legal advice and counsel clients in very narrow areas of the law such as divorces, child custody and evictions.

Rebecca Sandefur, a sociologist at Arizona State University, and Matthew Burnett, senior program officer at the American Bar Foundation, have studied “lawyerless legal services” and see the use of limited licensed professionals as a response to a “very real need.” The pair described the programs as providing solutions that are proportional to the access-to-justice problem.

Many individuals with legal problems, particularly those in the working and middle classes, are having to find their own way without an attorney.

Sandefur and Burnett cited data from the programs, which show that the services provided by limited licensed professionals is as good or even better than what attorneys are doing in those narrow contexts.

Key to the success is the kind of help the limited licensed justice workers can offer.

“I think the ability to give legal advice is critical,” Sandefur said. “… Legal advice is about being transparent about the process and what can happen and what your choices are and what the possible and probable outcomes are of those choices.

“That’s something that people really need,” she continued, “particularly when they’re in crisis or in uncertainty or there’re big stakes.”

Vanderburgh Superior Judge Leslie Shively is steadfast in his assertion that people cannot effectively navigate the legal system without an attorney. Knowing the law and understanding the process for resolving disputes requires the expertise of lawyers.

“The fact of the matter is just giving them forms and putting on seminars is great given the fiscal constraints we have right now, but it doesn’t really accomplish what needs to be accomplished — that is, having them having legal representation,” Shivley said of self-represented litigants. “If this were a medical clinic and a person needed an appendectomy, you wouldn’t give them a treatise on how to take their appendix out.”

‘Pretty good place’

The Legal Resource Center is working to expand its services by enlisting attorneys to volunteer a few hours to assist with whatever issue walks in the door. At the end of December 2022, the center had recorded 28 volunteer lawyer hours, with the assistance ranging from calling a landlord to resolve a dispute with a tenant to helping file a petition in a family law matter.

Clarissa Finnell, family law practitioner at Schultz & Pogue, has volunteered at the Center, working two 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. shifts and preparing for a third. She stayed busy, assisting a steady stream of self-represented litigants who presented mostly family law questions.

The skills needed for doing the volunteer work, she said, are just being able to sit and talk to people.

“I think most attorneys are good at that,” Finnell said. “It’s just the communication skills and being able to listen and figure out what the problem is and point them in the right direction.”

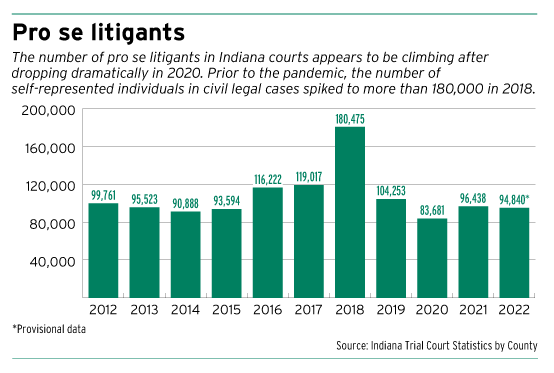

Gooden highlighted the reason for establishing the center by pointing to the growing number of self-represented litigants appearing in court.

She said she sees the resource as not only giving individuals vital assistance, but also providing the courts with a place to send pro se parties when they have not filled out a form properly or are confused by the proceeding.

“For the Legal Resource Center, I think our navigators are really meeting a need and they’re doing a great job,” Gooden said. “And if we continue to have volunteer lawyers give up their time, then I think we’re in a pretty good place.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.