Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowSome of the numbers surrounding the topic of website accessibility can look daunting.

Take 49.9 million, for example. That’s how many accessibility errors were detected across 1 million homepages in an analysis from the Institute for Disability Research, Policy, and Practice at Utah State University. That’s an average of about 50 errors for each page, ranging from text with low contrast to images that don’t have alternative text.

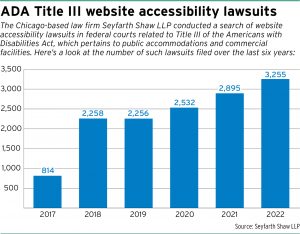

Then there’s 3,255 — the number of website accessibility lawsuits filed in 2022 in federal courts related to Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act, according to research from Chicago-based law firm Seyfarth Shaw LLP. Just five years prior, that number was 814.

But maybe the most intimidating part of website accessibility is the uncertainty, which can’t be captured in a number. That’s because there aren’t blanket regulations when it comes to what websites are supposed to do to be considered compliant under the ADA.

The U.S. Department of Justice issued guidelines in 2022 with examples of website barriers — videos without captions and no keyboard navigation, for example — and an explanation of the difference between state and local governments covered under Title II and businesses that are open to the public under Title III.

The U.S. Department of Justice issued guidelines in 2022 with examples of website barriers — videos without captions and no keyboard navigation, for example — and an explanation of the difference between state and local governments covered under Title II and businesses that are open to the public under Title III.

The DOJ also included examples of cases, including an agreement in 2016 with Miami University in Ohio to, among other things, modify webpages to conform to guidelines from the World Wide Web Consortium if a qualified student with a disability requests that.

Adam Bialek, co-chair of the Intellectual Property & Technology practice at New York-based Wilson Elser Moskowitz Edelman & Dicker LLP, said part of the reason there have been more cases filed recently is the pandemic.

There has always been a “cottage industry” of plaintiff firms filing cases related to physical violations under the ADA, Bialek said. But when businesses had to close their doors in 2020 and shift almost entirely online, that opened the door to new opportunities for accessibility lawsuits related to websites.

Wilson Elser is part of a legal panel assembled by the company AAAtraq, which works with companies to make their websites more accessible. AAAtraq insures the companies against litigation, so if they do face an accessibility lawsuit, Wilson Elser is one of the firms that could be assigned to defend the case.

While the number of cases has grown since 2020, the data from Seyfarth shows a spike in cases starting in 2018.

For an earlier catalyst than the pandemic, Jennifer Rusie, a principal and office litigation manager in Jackson Lewis P.C.’s Nashville, Tennessee, office, pointed to 2015 statements of interest from the DOJ in lawsuits against Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The National Association for the Deaf filed the lawsuits, alleging violations of the ADA and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.

“The ADA applies to websites of public accommodations,” the DOJ’s statement read in the Harvard case, “and … the ADA regulations should be interpreted to keep pace with developing technologies.”

“It just exploded,” Rusie said of the cases.

But cases related to websites are much trickier than traditional ADA cases, she said, not just because of the nature of how websites can change over time, but because courts haven’t agreed on how to apply the ADA — crafted with the physical world in mind — to online spaces.

Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP partner Jon Bomberger wrote in an email to Indiana Lawyer that some federal courts have ruled the ADA implies that a public accommodation has to be a physical space, while others have ruled that a website can be a public accommodation if it’s used in connection with a physical location. Then there are other federal courts that have said a website is a public accommodation, regardless of the presence of a phyiscal location.

There is also uncertainty regarding the standing of a plaintiff to sue, Bomberger said. Some federal courts have tossed cases brought under Title III if the plaintiff can’t demonstrate that they intended to visit and utilize the defendant’s services.

The United States Supreme Court has agreed to hear a case — Acheson Hotels, LLC v. Laufer, 22-429 — that Bomberger said will hopefully provide clarity on the standing question.

‘File and settle’

Very few cases related to website accessibility have gone to judgment, according to John Egan, a partner at Seyfarth, with the vast majority getting resolved before discovery. Egan called it the “file and settle model,” in which many businesses are staring down the threat of the steep cost of litigation and legal fees and decide to settle early as an economic decision.

The way it’s been playing out, Egan said, is “not ideal” when it comes to delivering the mission of the ADA.

The research from Seyfarth shows three states house the majority of federal ADA Title III lawsuits: New York, California and Florida. In 2022, New York led the way with 3,173 such cases, while the No. 4 state on the list, Texas, saw only 348.

The research from Seyfarth shows three states house the majority of federal ADA Title III lawsuits: New York, California and Florida. In 2022, New York led the way with 3,173 such cases, while the No. 4 state on the list, Texas, saw only 348.

Rusie, of Jackson Lewis, said there isn’t much caselaw because of the high rate of settlements. And because the settlements tend to be in the range of low four-figures to high five-figures, her clients see the potential for a lawsuit as “more of a nuisance.”

“It’s not like a top-of-mind worry,” Rusie said, “because these aren’t multimillion-dollar cases, but it’s a nuisance because there’s nothing they can really do to ensure they’re compliant.”

The Department of Justice announced in 2022 its intent to start the rulemaking process to enact website accessibility regulations that would be applicable to state and local governments under Title II of the ADA.

‘There’s a market there’

Mark Pound is the CEO of CurbCutOS, a company that helps businesses make their websites — along with apps, documents, videos and anything else digital — more accessible for people with disabilities.

Rather than seeing that work as a cost, Pound said companies should view it as an investment.

According to CurbCut, the disability community represents a $1.2 trillion market that Pound said is “widely ignored.”

“There’s a market there,” Pound said, opining that many people also discount the elderly who may be visually impaired.

CurbCut has had “well over” 200 clients over the years, Pound said, adding that it grew by 217% in 2022, and revenue in the first quarter of this year has already exceeded last year’s.

Pound said the growth is related to two main factors: increased awareness and a willingness to be proactive rather than chance a lawsuit.

Still, Pound and the lawyers who follow these cases say it’s not practical for a website to be 100% compliant. Minus the fact that it’s not completely clear what compliance means online, it’s also true that websites change a lot.

“Is anything ever 100%?” Pound asked. “That’s the pursuit of perfection, which will just drive you crazy.”

Rather, Pound said, the point is to make an effort.

“You’re doing something that a lot of others aren’t doing,” he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.