Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowSometimes when a staff member at the Hammond Legal Aid Clinic answers the phone these days, they hear people struggling to catch a breath and they know the callers have been crying for hours.

The economic devastation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has kept the calls for help coming to the clinic in northwest Indiana. People are trying to stay in their homes, pay their bills and care for their families, but more households are falling into poverty.

Kris Costa Sakelaris, executive director of the Hammond clinic, hopes the economy will rebound and families will recover. Still, she is not convinced that getting the coronavirus tamed will automatically bring a return of financial stability. She believes some jobs are gone forever, especially in the restaurant and tourism industries, and the help wanted signs she sees posted along the roadside are for jobs that pay less than what workers were making before the shutdown.

Other legal aid providers share Sakelaris’ fear. They expect that when the moratoriums on evictions end and the government support of stimulus checks and unemployment supplements runs out, the current wave of need will turn into a tsunami.

“I’m not sure we’ve seen the bottom yet,” Sakelaris said.

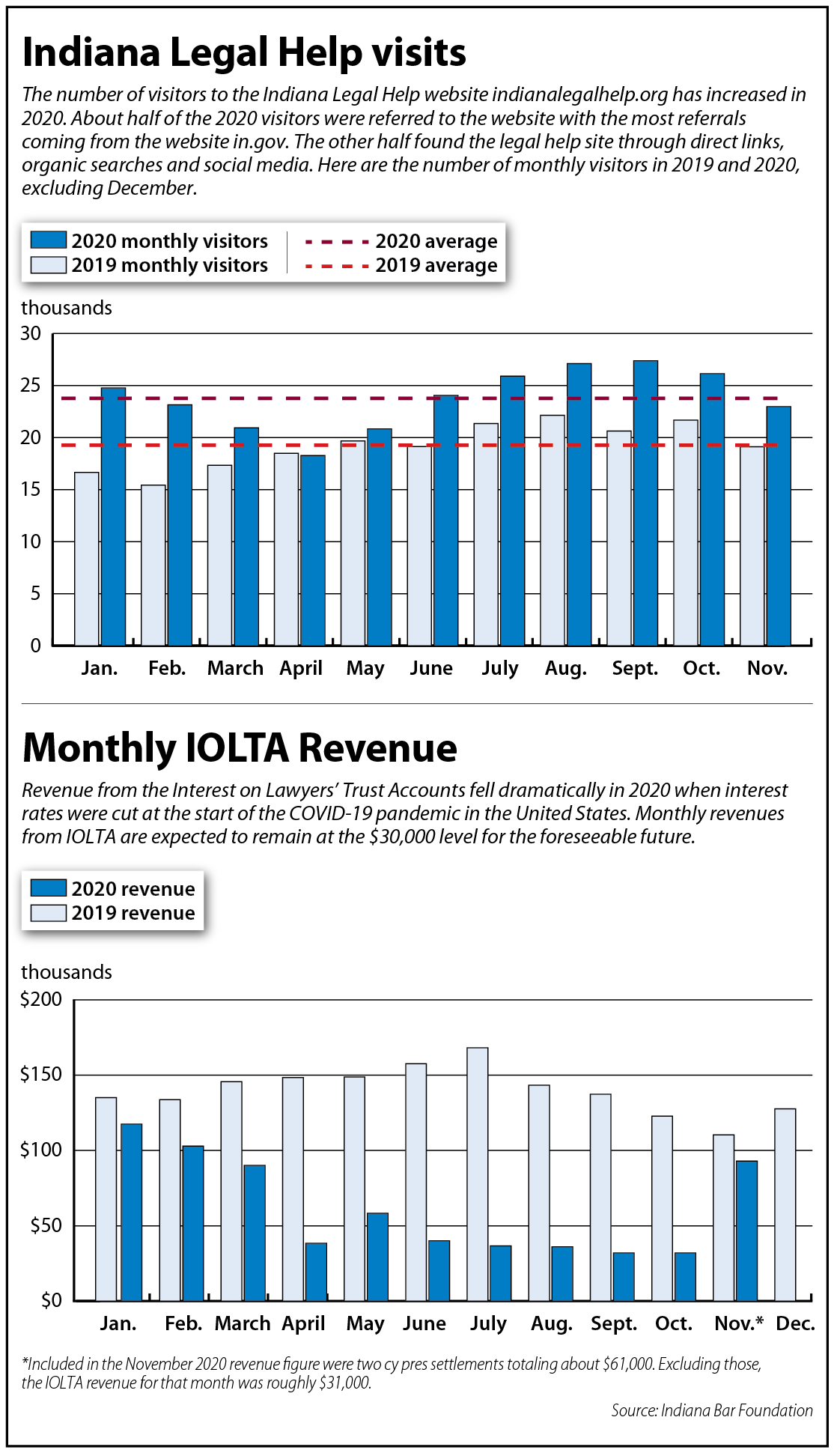

The Indiana Legal Help website, which offers court forms, links to other agencies and information for hiring an attorney, offers one glimpse at the rise in demand for civil legal aid during 2020. Through November, an average of 23,771 people logged on to the website each month, outpacing the 2019 average of 19,244.

How to marshal their resources and respond to the calls for assistance has legal aid providers worried. They talk about triaging the clients to determine who needs help the most and the potential for rationing services.

Looming evictions with so many Americans unable to pay their rent have been at the forefront of concerns, but legal aid offices and pro bono attorneys see other issues on the horizon. They expect more filings for bankruptcy and guardianships, and they believe more people will reach out for legal assistance with problems connected with consumer debt and domestic violence.

Underpinning their ability to help is the need for money.

To shore up their finances, some providers have received a loan from the Paycheck Protection Program. In addition, Sen. Ron Grooms, R-Jeffersonville, is preparing to introduce a bill during the 2021 session of the Indiana General Assembly that would raise the supplemental civil legal filing fee from $1 to $3.

The boost in filing fee revenue will help, but as Charles Dunlap, executive director of the Indiana Bar Foundation, pointed out, the coronavirus-induced downturn is putting stress on every part of the system and made just about every problem worse. Legal aid offices will struggle to handle the fallout for years to come.

“It’s like the economic crisis poured gasoline on all these other issues that are out there,” Dunlap said. “… I’ve never seen anything like this, just the depth of the impact and how quickly it happened.”

Reducing the pressure

Indiana Legal Services has recorded a strong uptick of calls. From June to October, intakes ballooned, hitting a high of 2,090 in September.

The organization has been working to meet the increased demand. As of Dec. 24, 2020, ILS had closed 11,713 cases, which compares to the 11,657 cases that were counted as closed for the year 2019. Also, with a $1.8 million PPP loan, ILS has temporarily hired 20 more employees, mostly attorneys.

Jon Laramore, ILS executive director, noted the economic upheaval has made the group of people who are income eligible for legal aid “substantially larger” than in 2019.

“We always have represented people who work because there are so many low-wage workers whose earnings keep them below the poverty line in normal times,” he said. “Now more people are moving into that category after they have lost a job or lost hours.”

To help more people, Scott Wylie, executive director of the Indiana Pro Bono Network, said the members of the entire legal assistance team across the state will have to collaborate to best match available resources with clients’ needs.

Wylie described the collaboration as looking like a triage system. The clients with complex cases would be paired with a legal aid attorney for representation while clients with more straightforward legal issues would be directed to the Indiana Legal Help website. Wylie said some people with just a little bit of help are able to handle their legal problems themselves, which reduces the pressure on the civil legal aid system as a whole.

A silver lining of sorts brought by the pandemic has the possibility of alleviating some of the stress on civil legal aid in Indiana. Wylie sees the increased use of and growing comfort with technology as leading to some permanent changes in the justice system.

For example, courts moving routine procedures or minor issues to an online platform has produced some unexpected benefits. A virtual hearing for a $75 speeding ticket or a pretrial conference means the participants will not have to take a half-day off work to appear but instead can step away from their job for a short period and join by video conference.

“We’ve learned a lot of ways to make the court system better for poor people,” Wylie said.

Alongside courts going virtual, a $125,000 technology grant from Legal Services Corp. to Indiana Legal Services is being used to make the Indiana Legal Help website more robust. The Indiana Bar Foundation, Coalition for Court Access and the Indiana Supreme Court are among the groups working jointly on the project.

The money from what is believed to be the first technology grant awarded to ILS is helping to develop a handful of new apps that will provide information on the legal process for expungements, restoring driving privileges and changing name or gender markers, according to the Indiana Bar Foundation. Also, instructional videos and graphics are being created to teach people how to interact with the court system.

Technology and online applications are not the solution to problems facing legal aid, Dunlap said. But he echoed Wylie in explaining that some people will be able to use these tools and do what they need by themselves.

Funding drop

Funding drop

As is typical in any downturn, when demand for legal aid increases, the money to support the services decreases.

One key source of funding for the Pro Bono Network in the state is the Interest on Lawyers’ Trust Accounts. For more than a year, revenues from IOLTA had been topping $100,000 a month, but the slash in interest rates at the start of the pandemic has sent the returns into a nosedive. The recent high of $168,214 in July 2019 had dropped to $36,704 in July 2020. The Indiana Bar Foundation, which administers IOLTA funds, does not anticipate the revenues will rise anytime soon.

“We’re at rock bottom as of July 1 and will be for a couple of years,” Dunlap said.

Returns from the program also plunged during the Great Recession but at that time, the bar foundation had built a sizable nest egg that helped sustain funding levels for a couple of years. For this downturn, the reserves are not as big because there was not as much time between the recovery from the last recession and the pandemic to sock money away.

Dunlap said enough has been saved to keep the same amount of money, about $1 million, flowing to the pro bono system through 2021. The funding shortfall will likely arrive in 2022, but several options for bridging the financial gap are being considered.

Among them is Grooms’ bill to raise the pro bono legal services fee on all civil cases filed in state courts.

Historically, the $1 civil legal filing fee has returned roughly $360,000 annually to legal aid coffers. But the pandemic’s disruption of court proceedings has taken a bite from the fee revenue, dropping the 2020 amount to an estimated $260,000.

A fee of $3 along with civil court filings bouncing back to normal levels would help make up nearly all of the lost funding from IOLTA, Dunlap said.

Grooms, a pharmacist by training, is optimistic the increase in the filing fee will get to the governor’s desk. Even though some in the Statehouse will be shocked by the percentage of the increase, Grooms plans to counter that the actual dollar amount is “very small.” Moreover, he will emphasize that the filing fee is not a tax on every Hoosier but rather a targeted fee that is paid by the people who use the judicial system.

Finally, he said he is prepared to compromise and reduce the fee to $2 if that gets more legislators to support his bill.

Ultimately, legal aid providers, like many people around the world, are looking to science for relief. “We hope that a vaccine allows society to go back to some semblance of normal so people are able to re-enter the economy have less need for our help,” Laramore said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.