Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA new state law seems like something that advocates of paper ballots would cheer about.

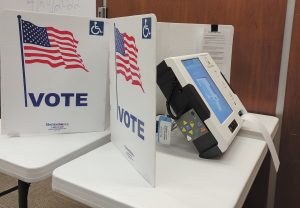

The language in House Enrolled Act 1116 moves up the date by which Indiana’s electronic voting machines must produce a paper trail. Rather than making Hoosiers wait until December 2029 to get paper confirmation when they vote, which can then be used to double-check the accuracy of the direct-recording electronic voting machine, or DRE, they will be able to get that paper confirmation by the November 2024 general election.

DRE machines have been coming under increasing concern for security breaches and software glitches that could result in the votes not being recorded and counted accurately. Voter-verified paper audit trail, or VVPAT, devices are presented as the answer to that potential problem, but paper ballot supporters say the printouts from the devices will not ensure correct vote tallies.

Linda Hanson, co-president of the Indiana League of Women Voters, explained the opposition to HEA 1116 was not to moving the date forward to having paper audit trails. Rather, opponents object to adding the VVPATs to the MicroVote brand DRE machines used in Indiana.

“The DRE is the real problem,” Hanson said. “The VVPAT just aggravates it and (the legislators) think they’re fixing it, but the problem is that they should just get rid of the DREs.”

Indiana is one of just a handful of states that use DREs without VVPATs, according to a 2022 report by The Brennan Center for Justice and Verified Voting, a nonpartisan organization. The report stated security experts have cautioned that DRE machines pose a unique security risk, noting “a number of these models” have incorrectly registered voters’ choices in the past.

In Indiana, 56 counties, shown on the Verified Voting website, employ DRE systems, with only 13 of those having VVPATs for all voters.

HEA 1116 was signed into law by Gov. Eric Holcomb on March 14. Indiana Secretary of State Holli Sullivan said her office has already supplied the 8,010 VVPATs needed to finish outfitting the DRE machines in the state. The cost was $12 million, drawn from the state’s general fund.

“I’m very confident in all our certified voting equipment that we utilize in Indiana elections,” Sullivan said, describing Indiana as a national leader in election security and integrity. “… All our equipment, including VVPATs and DREs, must go through the exact same rigorous certification process that includes ensuring federal and state testing standards are met before they can be utilized in an election in our state.”

Like a grocery receipt

After the 2020 general election, Indiana did not face the accusations of widespread voter fraud that continue to plague states like Wisconsin and Arizona. However, Huntington County Clerk Shelley Septer learned from the daily phone calls that some Hoosier voters were worried.

The COVID-19 virus kept many people stuck vinside their homes watching more television, so when they saw stories about voter concerns, they would dial the clerk’s office. With the calls coming so frequently, Septer began watching the morning news so she could prepare for the questions that would be coming.

A story about problems with abandoned mailboxes prompted Septer to start her day with a call to the local post office to ask if the county had any mailboxes no longer used. She and her staff were then able to assure callers that any mailbox into which they dropped their absentee ballots would be checked.

The third generation in her family to serve as Huntington County clerk, Septer said she supports the installation of the VVPATs because she believes they will give voters more peace of mind.

“I have so much confidence in the machines that we use that I wouldn’t have been probably one of them that would’ve said we absolutely need this,” Septer said, adding that her perspective was changed by the concerns she regularly heard from local residents. “… I would say, if it’s just for voter confidence alone, I think that that’s a great thing because I feel like we’re doing our part to make sure that people are confident that their votes are being counted.”

HEA 1116 requires that counties using DRE equipment have at least 10% of the voting machines outfitted with a VVPAT by July 1 of this year.

Sullivan explained the VVPAT creates a paper record — which is small and “looks a little bit” like a grocery store receipt — which each voter can examine to confirm the DRE accurately recorded his or her selections. Then the voter will have the option of casting the ballot or making a change if something is marked incorrectly.

County clerks keep the VVPATs with the paper ballots. If a candidate wants a recount, the paper slips can be reviewed to double-check the final vote tally.

Both Hanson and Barbara Tully, president of Indiana Vote By Mail, said they have concerns about the small size and durability of the paper. The two signed on to a letter sent to Indiana senators opposing VVPATs.

Voters might get frustrated straining to read the VVPAT ballot and just cast their electronic ballots without verifying their selections, they said. Also, the VVPAT rolls are “extremely ill-suited” for audits and recounts. The ballots are printed on thermal paper that is prone to ripping, smudging and fading, they said.

“The simplest thing to do is to go to a hand-marked paper ballot,” Tully said. “It doesn’t break. It doesn’t need technical support at polling places. You don’t have any of the technology concerns that you have when you’re putting DRE and VVPAT machines out in the number of places that you need to put them.”

According to Sullivan, the VVPATs are being tested and certified by the Voting System Technical Oversight Program in the Bowen Center for Public Affairs at Ball State University. When Indiana Lawyer asked VSTOP for information about the certification process, the program directed the question to the Secretary of State’s Office. The secretary of state did not respond to a separate inquiry about the certification.

“I think Hoosiers have come to share that technology is something that they want in the voting process because we have now seen quick election results,” Sullivan said when asked why Indiana does not use a paper ballot system. “… When you can combine paper and the technology, you have the increased security as well as fortified the ability to make a timely decision and to also execute recounts quickly and in a way that saves taxpayer money.”

Voter confidence

One recent morning, perennial candidate Denise Paul Hatch of Marion County was outside the Indianapolis City-County Building campaigning for Center Township constable. She was bundled in a tan winter coat with a bright pink scarf wrapped around her head. Also, her leggings sported multicolor marijuana leaves, a nod to her drive to legalize marijuana, which has earned her the nickname, “the weed lady.”

Hatch said voters do not have confidence in the system, although their concerns are not about the ballots being counted accurately. Instead, they complained to her that their votes do not matter because their candidates never win.

However, Hatch encourages them by noting that even though she won only 16% of the vote in the last mayoral primary, several officials have since joined the push for legalization.

“I didn’t win my race,” Hatch said, “but something got done.”

Bartholomew County Clerk Shari Lentz agreed that voter confidence is a paramount concern.

The south-central Indiana county installed VVPAT devices on all its DRE machines as part of a pilot program in 2018. The voters in her community, Lentz said, are “very comfortable” with voting on electronic equipment and are confident their votes are counted correctly.

Some voters didn’t notice the VVPATs, but Lentz noted others have and are “very appreciative.” Although she has never fielded a complaint or concern about voter fraud, she said she views the VVPATs as giving voters extra assurance.

“We want voter confidence,” Lentz said. “You know, there’s not really a reason to have an election if our voters can’t be confident in the outcome.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.