Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Although she was never admitted to the intensive care unit when she tested positive for COVID-19, Dr. Babar Khan said his patient was experiencing increasing trouble with memory and attentiveness. She later developed postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a symptom of COVID that results in dropping blood pressure.

“She was not able to get back to her job to grade and provide lectures for a while,” said Khan, a pulmonary and critical care specialist at Eskenazi Health. “Then she had a lot of balance issues and so she needed gait training and to drink fluids which are rich solvents to keep her blood pressure up.”

More than 18 months later, Khan’s patient is finally on the mend. But it was a long journey to get there.

“She’s still dealing with the symptoms,” Khan said. “Enough that it is affecting her quality of life.”

Khan has treated roughly 150 patients suffering from “long COVID.” Some people who have been infected with COVID-19 can experience long-term effects from their infection that include a wide range of ongoing health problems lasting from weeks to years.

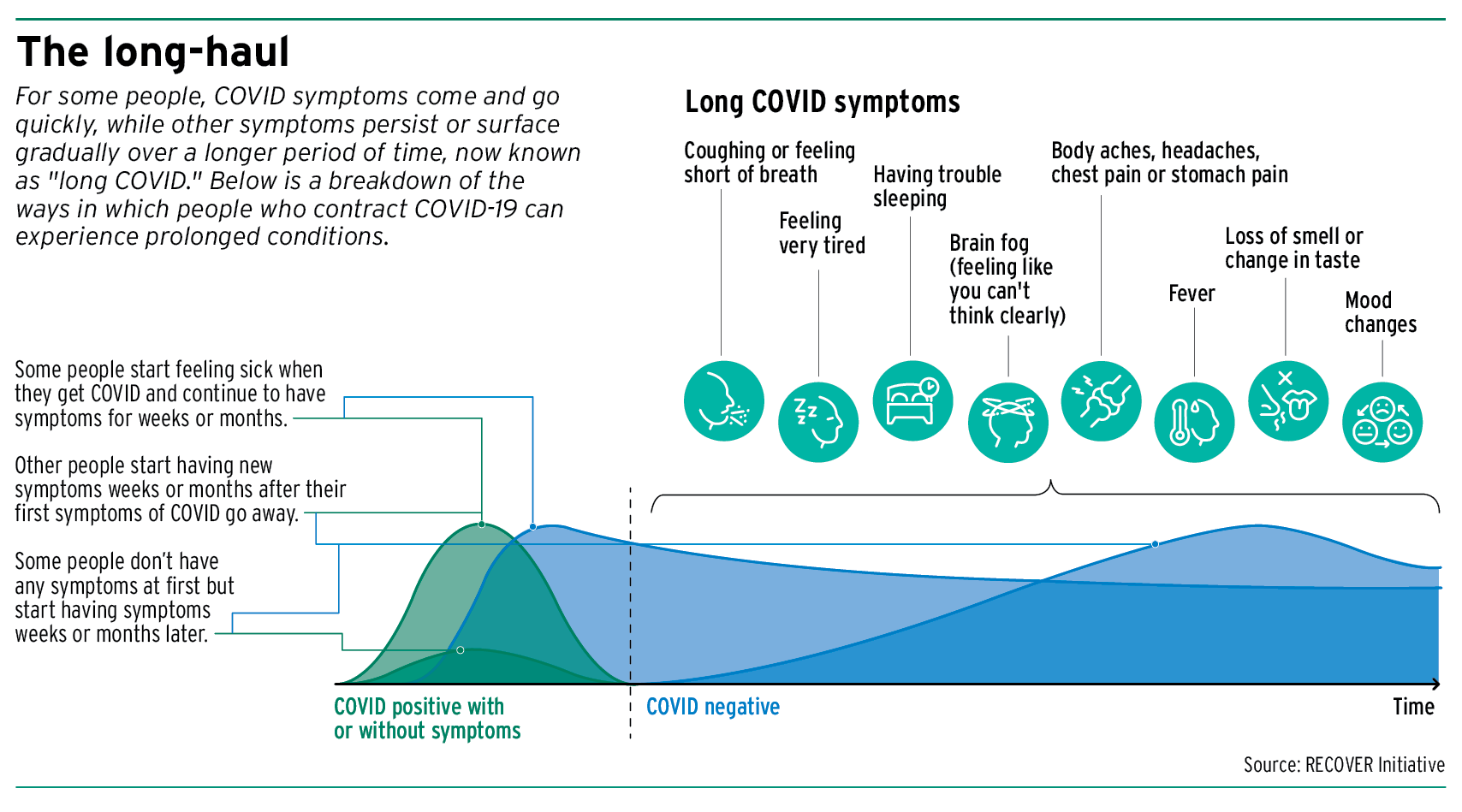

For some people, COVID symptoms come and go quickly, while others persist or surface gradually over a longer stretch of time. As of now, Khan said no one knows just how long “long COVID” can last.

“For some people it can last one month, and for some people it can last three years,” he said.

More than 40% of American adults reported having COVID-19 in the past, and nearly 1 in 5 of those are currently still having symptoms of long COVID, according to a June Household Pulse Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The same study found that overall, 1 in 13 adults in the U.S. have long COVID symptoms, which last three or more months after first contracting COVID-19. Younger adults are more likely to experience long COVID than older adults, with 17.8% of 18-to-29 year olds experiencing persistent symptoms compared to 10.9% of 60-69 year olds.

‘Constellation of symptoms’

Khan, who is also a Regenstrief Institute scientist, described long COVID as being a constellation of symptoms experienced long after someone has been infected with and tested negative for COVID-19.

“And by long term, I mean by persistence of certain symptoms after four weeks is usually classified as long COVID,” Khan said. “From four to 12 weeks, some people call it subacute symptoms, and from 12 weeks onward, some folks describe it as chronic COVID-19 symptoms.”

Contracting COVID-19 can result in patients experiencing persistent symptoms like fatigue, headaches, loss of smell and hair loss. There can also be a slew of cognitive problems, Khan noted, which include “brain fog” or memory loss, an inability to pay attention, issues with executive function, depression and anxiety.

Physical struggles can also persist, leaving individuals with heavy fatigue that prevents them from going back to work, Khan added.

“On top of that, they’re going to have long-term symptoms with cough, shortness of breath, being oxygen dependent, especially if they were in the intensive care unit,” he said. “So if you put all of these multiple symptoms together, that’s the term that we start calling long COVID.”

Of those affected, women are more likely than men to currently have long COVID, with 9.4% of females reporting long COVID symptoms compared to 5.5% of males, according to the Household Pulse study. Additionally, nearly 9% of Hispanic adults currently have long COVID, higher than non-Hispanic white (7.5%) and Black (6.8%) adults, and over twice the percentage of non-Hispanic Asian adults (3.7%).

Back to baseline

Dr. Fen Lei Chang, medical director of Parkview Health Neurosciences and the Parkview Post-COVID Clinic in Fort Wayne, said not all patients have the same set of disease pathophysiology and symptoms.

“It can cause significant disruption in life and work,” Chang said.

The Parkview Post-COVID Clinic provides care and support for Hoosiers with post-acute sequelae of COVID-19, or PASC, commonly known as COVID-19 “long-haulers.” Services offered at the clinic include neurology, physiatry, neuropsychology, occupational therapy, physical therapy and pharmacy service.

Since its opening in March 2021, Chang said the clinic has served around 550 patients. Its goal is to help long-hauler Hoosiers return to the life they knew before COVID-19, he said.

Chang gave the example of a patient in her 50s with a history of hypertension, diabetes and obesity who originally tested positive for COVID. Her symptoms included a fever, cough, shortness of breath and excess fatigue as well as loss of taste and smell.

“She had trouble with concentration and memory, and she described herself as having ‘brain fog,’” Chang said.

Although she noted progressive improvement of her respiratory status in two to three weeks, Chang said his patient was still struggling with brain fog, fatigue and a loss of taste and smell. Four months after her COVID diagnosis, she was seen at the long-COVID clinic and was diagnosed with orthostatic hypotension.

“She also underwent physical therapy with emphasis on gradual exercise enhancement,” Chang said. “Speech therapy was engaged to help with memory and attention strategies. Lifestyle review, including stress management, weight management and proper sleep hygiene was emphasized. About two months later, she was almost back to her pre-COVID baseline.”

Impact over time

As Hoosiers move incrementally into a post-pandemic world, Khan said some aren’t physically feeling like themselves anymore. For some, that could mean they have effects of long COVID and are unaware.

“Some of the patients don’t even have any complaints. But when we screen them, we find out that they have these impairments, right?” he said. “But people cannot put a finger on the symptom. So that’s why I think as physicians or as health care providers, we need to be really cognizant that some people cannot put a name to the symptom.”

Khan said many are unaware of long COVID or how it can impact quality of life, even if it’s just a minor change.

“If somebody would tell me that, ‘Hey, it’s not a big deal, you can get COVID-19 and you’ll be OK because you’re vaccinated’ or, ‘This is like a flu and not many people have this problem,’ I don’t want to be one of those people who are not able to go to my job,” Khan said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.