Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowNearly 20 years’ worth of data tracking trends of federal civil pro se filings show that civil rights cases make up the second-highest percentage of filings, next to pro se prisoner cases. In recent years, a growing number of those cases have targeted law enforcement or other government actors.

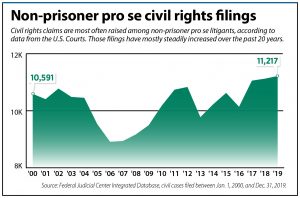

The data, gathered by the Judiciary Data and Analysis Office of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts for the years 2000 to 2019, reflects non-prisoner pro se litigants most often filed civil rights cases.

From 2009 to 2012, filings of pro se civil cases by non-prisoners increased every year. Most of the growth during that period was caused in part by an increase in civil rights claims.

Over two decades, non-prisoner civil rights filings consistently moved on an upward trajectory without major spikes or drops. While there was a slight decline between 2002 and 2006, the civil rights cases climbed up to a new peak in 2012. Continuing that trend, pro se civil rights filings were at an all-time high in 2019 for the timeframe being studied.

Despite that steady increase, some legal practitioners say they expected the numbers to be higher.

“It’s slight trend up, which in some ways I find surprising. To be honest, I would expect it to be more given the availability of resources,” said Thomas Wheeler, a member at Frost Brown Todd LLC in Indianapolis. “If someone wants to pursue a case, they don’t necessarily need to have an attorney.”

Tracking trends

Wheeler, who has previously served as acting assistant attorney general for the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division and has focused primarily on education and law enforcement in 35 years of civil rights experience, said the cases he sees have evolved over time.

For example, education cases he encounters in 2021 are focused on due process concerns related to student discipline like they were in 1987, but now there’s more Title IX cases. There’s also been a cultural shift, he said, with more cases focused on transgender issues and critical race theory.

Special education and pro se employment cases have remained steady, Wheeler continued, but trends in civil rights work in law enforcement have evolved. In years past, pro se wrongful arrest and excessive force allegations rarely involved weapons. That’s not the case today.

“It would be a police officer using a baton when they should have physically restrained (the individual). I think the volume of those claims is about the same, but they have changed tremendously over the past four or five years,” Wheeler said.

Indianapolis attorney Andrea Ciobanu said she gets a reasonable number of calls regarding Americans with Disabilities Act violations and a handful of calls about education, but most civil rights requests that come her way often center on police accountability concerns, including excessive force, police brutality and false imprisonment claims.

“We definitely get the most calls about civil rights,” Ciobanu said of her practice, which also focuses on family law, personal injury and mediation.

While many of her civil rights cases are settled out of court, Ciobanu said some do go to trial. Prisoner cases are more difficult to represent, she said, pointing to the immunities involved and requirements that prisoners exhaust their administrative remedies.

Police brutality cases can also be a challenge because of qualified immunity, she added.

“I have to turn down a lot of cases just due to our current caseload and the demands these types of cases require,” Ciobanu said. “Generally speaking, federal cases, and civil rights in general, require more work than the other types of cases I take on, so I have to take that into consideration when taking on new cases.”

Locally, Indiana’s federal courts have seen fluctuating numbers of pro se civil rights filings in recent years. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana has seen a slight uptick in non-prisoner pro se civil rights filings, which accounted for 5.6% of cases in 2019, 6% of cases in 2020 and 7.1% of cases as of Aug. 31, according to data provided by the court.

Chief Judge Jon DeGuilio of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Indiana said he has seen a more fluctuating trend. Its median number of civil rights claims filed between 2006 and Aug. 31 settled at 103 filings, with a four-year stretch of its highest total filings from 2009 to 2012.

“I’m surprised the numbers aren’t greater,” DeGuilio said, admitting he was surprised by the sheer number of pro se cases he saw when he first took the bench. “I can’t anecdotally speak to any changes in trends or the types of cases that have been filed. But from my own docket, the cases seem pretty consistent over the years.”

The vast majority of pro se civil rights cases DeGuilio encounters in court are classified as “other,” he said, including Section 1983 claims unrelated to employment that encompass a large number of cases, including claims against police officers. Those can include excessive force, failure to intervene and false imprisonment.

“It was not surprising that so many of these cases are filings against state governmental actors for their conduct — I see that pretty frequently,” the chief judge said.

Getting help

Mixed among the calls clogging Ciobanu’s phones are a hefty number of requests from litigants who started off their cases pro se but later realized how difficult the process can be.

“I can only take some of those at that point because sometimes the case is too far along and their deadlines are passed,” she said. “I take those every once in a while, but very few.”

Often, she said, pro se litigants will file a complaint that might survive the screening process, but they hit a wall once it gets to formal discovery or summary judgment.

“It’s sometimes too difficult, and if they haven’t been assigned a pro bono attorney and they’re on their own, a lot of times they realize they need help,” Ciobanu said.

DeGuilio said he’s always believed pro se litigation is concerning for that very reason.

“You have lay people trying to traverse the federal system, which is not an easy thing to do. So in terms of filing a claim, stating it in a proper fashion and filing proper motions and responses, especially dispositive motions like motions to dismiss and summary judgment, pro se litigants are at a great disadvantage because they don’t know the law,” he said.

Despite the legal complexities litigants must overcome, Ciobanu said she is often amazed at their ability to navigate the federal system.

“I think that people are becoming more aware of their rights,” she said. “I think due to awareness, media and even national cases, many more people are willing to pursue civil rights cases.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.