Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIndigent defense reform has long been a priority in Indiana, with a 2016 report from the Sixth Amendment Center triggering the most recent round of reform efforts. Now, new data is lending support to the public defense community’s requests for additional resources.

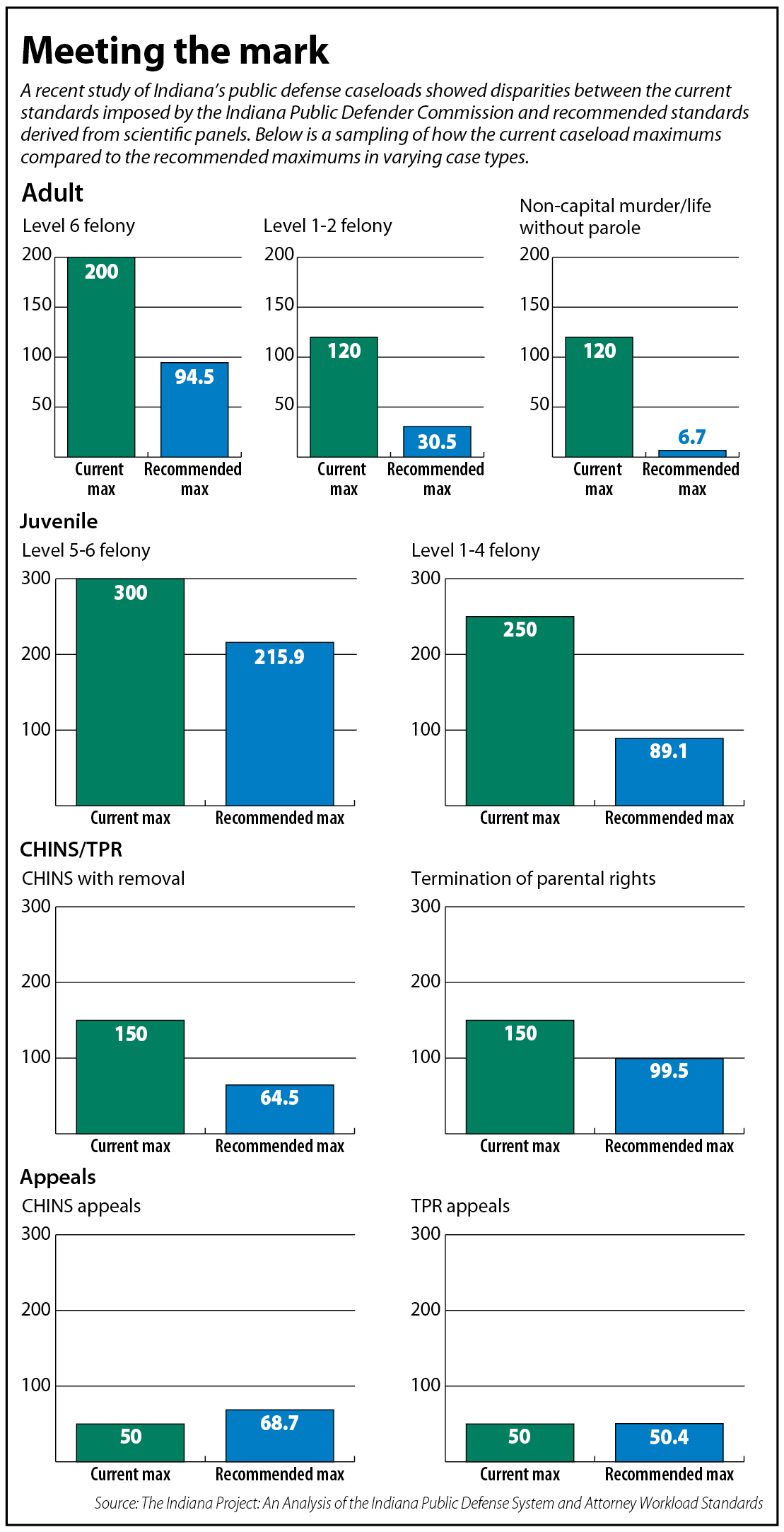

The Indiana Public Defender Commission last month released an analysis of caseloads in Indiana, showing disparities between actual and ideal workloads. That data has led public defense experts to one conclusion: there’s still work to be done to ensure indigent Hoosiers receive quality defense.

The need for additional indigent resources is not new, experts say. But with new data demonstrating that need, experts say the report puts “meat on the bones” of their ongoing requests.

Some surprises

Completed by the American Bar Association Standing Committee on Legal Aid and Indigent Defendants and Crowe LLP, the report — “The Indiana Project: An Analysis of the Indiana Public Defense System and Attorney Workload Standards” — uses a predictive model known as the Delphi Method to gauge appropriate public defense caseloads. Public defenders and private practitioners were convened into “Delphi panels” to “provide professional consensus opinions regarding the appropriate amount of time an attorney should spend on certain case types to provide reasonable effective assistance of counsel … .”

The panels’ recommendations were then compared with the caseload standards the commission imposes on the 64 counties that participate in its indigent defense reimbursement program. There were two reasons the commission wanted to review its existing standards, senior staff attorney Derrick Mason said.

First, Mason said, the commission’s standards were initially based on standards from the 1970s — standards that have changed over time with new data and evidence from other states.

Second was the overhaul of Indiana’s criminal code in 2015. In particular, Mason noted that the criminal code reform created six felony levels in Indiana, compared to the four classes of felonies previously in place.

“When you go from four to six levels, we’re getting even further behind the times,” Mason said. “Now is the time, with some experience in other states, to take an evidence- and data-based approach to this problem.”

The commission went into the study expecting to find some disparity between the current standards and the panel recommendations, Mason said, and in some cases, the results were unsurprising. For example, defenders in the 64 participating counties have previously said that appellate standards could be increased, and the panels likewise recommended a 67% increase in the caseload maximum for miscellaneous criminal appeals.

But other results were more striking. For adult high-level felony cases, the panels recommended a 75% decrease in caseload maximums.

Explaining disparities

Based on anecdotal data about staffing shortfalls, the sometimes-substantial disparities uncovered in the report were not surprising to Michael Moore, assistant executive director of the Indiana Public Defender Council. But others were struck by some of the differences.

“I definitely thought the numbers were too high, but I have to say, I didn’t realize it was that big of a gap,” council executive director Bernice Corley said.

Realistically, Mason said, it was understood that no public defender could effectively handle 120 non-capital murder cases, as is allowed by the commission’s standards. What’s more, murder cases are not common enough to need a 120-case maximum. To that end, the panel recommendation — nine murder cases max without life without parole and 6.7 cases with LWOP — was not surprising.

Realistically, Mason said, it was understood that no public defender could effectively handle 120 non-capital murder cases, as is allowed by the commission’s standards. What’s more, murder cases are not common enough to need a 120-case maximum. To that end, the panel recommendation — nine murder cases max without life without parole and 6.7 cases with LWOP — was not surprising.

When looking at high-level felonies, defined as Levels 1 and 2, the disparity is at least partially attributable to the fact that the current standards were developed decades ago, Mason said. Also, high-level felonies are not as common as lower levels.

“One hundred twenty felony cases in general, I think, would be more appropriate than just high-level felonies,” he said.

An increase in duties could also be contributing to excessive caseloads, Corley said, pointing to the growth in forensic work. Even pretrial release — an area of reform meant to improve Indiana’s criminal justice system — creates additional duties for defenders as they argue the merits for their clients’ release.

Moore pointed to resource disparities as another cause of caseload disparities. There’s already an insufficient number of lawyers to handle public defense in Indiana, he said, with some counties having no local licensed attorneys at all. Small rural counties in southern Indiana tend to have the most trouble with staffing, he said.

Local challenges

Without a statewide public defense system, Indiana counties are free to structure their indigent defense services to fit their resources.

In Lake County, for example, only felonies are reimbursed by the commission, chief public defender Marce Gonzalez said. The juvenile court, however, opted out of the commission’s standard-based reimbursement program.

Gonzalez said his office is “pressing the limit” of felony cases his staff — all part-time except him and his first assistant — can handle while remaining within commission recommendations. He assigns cases to five salaried and two contracted attorneys in each of the county’s four felony courts.

But with COVID-19 creating a backlog in court dockets, Gonzalez knows the “logjam” will break once courts fully reopen. That means cases that were delayed because of the pandemic will need to be resolved, on top of the new filings his staff would already be handling. His solution to stay within commission standards is to create four “overflow” contract positions, which he has amended his 2021 budget to accommodate.

But a few counties over in Elkhart, interim chief public defender Jeffrey Majerek is facing pushback from county officials.

Majerek’s predecessor, the late Peter Todd, joined the commission’s reimbursement program in 2020 without county permission. It has since fallen to Majerek to get the county council’s buy-in for an additional two lawyers and one staffer, which it needs to stay in the program.

Majerek has had some success, increasing his support from just one council member to three, but he needs the support of four councilors to officially join the program. He’s also facing opposition from the local prosecutor’s office, which has said it would be unfair to devote additional resources to the public defender’s office only.

But Majerek isn’t giving up, saying commission participation would save the county money, help lower jail populations and improve client representation. Before he became interim chief, his 2019 caseload alone hit 189 felonies, including some murders.

Finding funds

The caseload report comes as other efforts for public defense reform are continuing in Indiana. It’s been two years since a public defense task force released reform recommendations, some of which have already been presented to the Indiana Legislature.

Corley is hopeful the 2021 General Assembly will be open to implementing some of those recommendations, such as reimbursement for misdemeanor cases, funding to support “holistic defense” and additional funding for the commission’s existing program. But given the state’s COVID-related fiscal crisis, Mason knows securing additional funds will be a tough sell.

For Andrew Cullen, public policy and communications specialist at the commission, the worst-case scenario would be a budget reduction.

“We’re going into a difficult budget cycle, so we are trying to be data-informed in our management of counties that choose to participate,” Cullen said. “At the same time, we’re terrified of what a budget cut could do to the system that is currently in place.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.