Subscriber Benefit

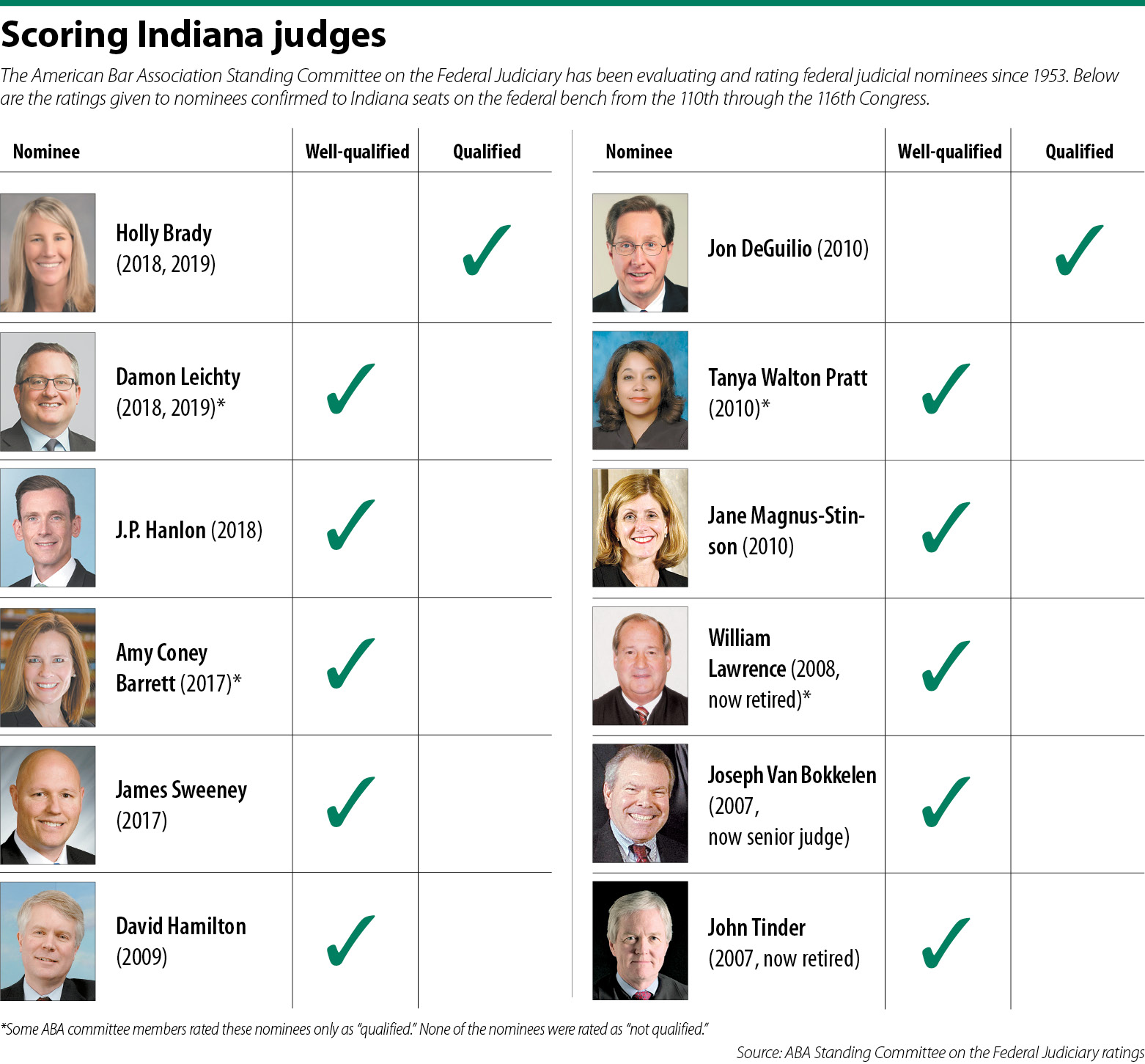

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowFor more than 60 years, the American Bar Association has publicly evaluated the qualifications of nominees to the federal bench. Sometimes the evaluations are tossed aside by senators and presidents, and other times they’re the deciding factor in whether a nomination sees the light of day.

But this practice is not unique to the federal bench. In Indiana, multiple bar associations regularly evaluate judicial candidates in both elections and merit-based selection systems. The practice also extends to Indiana’s appellate courts, where individual judges and justices facing retention are evaluated by the Indiana State Bar Association.

On the federal level, judicial ratings are often cast as partisan. But in Indiana’s state courts, bar leaders say they view their role as helping Hoosiers to impartially decide whether members of the judiciary are adequately serving their communities.

The Backgrounder

The ABA’s Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary, a 15-person committee with representatives from all of the federal circuits, is tasked with conducting judicial evaluations. The inner workings of the committee tend to be held close to the vest — the established policy is that only the ABA president or chair of the committee can respond to public inquiries — but a publicly available document known as the “Backgrounder” lays out the procedures that standing committee members must follow.

A three-part phrase is repeatedly given in the Backgrounder as the theme of judicial evaluations: integrity, professional competence and judicial temperament.

According to the Backgrounder, one committee member is assigned to evaluate each nominee. The process begins with the receipt of the nominee’s responses to the Senate Judiciary Committee’s questionnaire, and from there includes background checks, writing reviews and interviews with lawyers, judges, professors, deans and others who know the nominee.

According to the Backgrounder, one committee member is assigned to evaluate each nominee. The process begins with the receipt of the nominee’s responses to the Senate Judiciary Committee’s questionnaire, and from there includes background checks, writing reviews and interviews with lawyers, judges, professors, deans and others who know the nominee.

The nominee is interviewed near the end of the process and is given the opportunity to respond to any negative feedback. A summary report is then prepared, and that report becomes the basis for committee members to give a nominee a rating of well-qualified, qualified or not qualified.

If the standing committee settles on a not-qualified rating for a district or circuit court nominee, it prepares a written statement that is submitted to the Judiciary Committee. In the case of Supreme Court nominees, the standing committee always prepares a written statement, as those nominees are evaluated on the premise that their professional qualifications must be “exceptional.”

Indiana evaluations

The evaluation of Indiana judicial candidates varies from county to county, but the consensus among bar leaders is that judicial surveys are meant to provide the public with impartial insight from those who work most closely with judicial candidates.

At the ISBA, President Leslie Henderzahs said the evaluation of appellate judges up for retention is built on the organization’s goal of improving the administration of justice and promoting public understanding of the legal system. Bar members are given a yes or no question — should this judge/justice be retained? — but they are also given the opportunity to provide feedback directly to the judicial candidate.

In Vanderburgh County, where judges are elected, members of the Evansville Bar Association are asked to answer seven questions about judicial candidates on a scale of “poor” to “excellent,” President Sacha Armstrong said. The questions address legal experience, legal knowledge, industry and efficiency, temperament, impartiality and objectiveness, applying legal principals to fact, and whether the survey respondent would recommend the candidate for judicial office.

Merit-based selection is used in Lake County, but Shawn Cox, president of the Lake County Bar Association, said the LCBA still sends local attorneys a survey seeking feedback on the qualifications of judicial applicants. The survey results are distributed to the attorneys and public, as well as to the members of the Lake County Judicial Nominating Commission.

The Indianapolis Bar Association no longer evaluates judicial candidates now that its judges are appointed through merit selection. But when judges were facing contested elections, former IndyBar President John Trimble said the bar would distribute a survey asking for feedback of candidates’ judicial temperament, preparation, rulings and court administration.

Partisanship and politics

At the federal level, the acceptance of the ABA standing committee’s ratings often depends on politics. Most administrations since Eisenhower have given the committee advance notice of nominations before names are submitted to the Senate, but neither the George W. Bush nor the Donald Trump administration has provided that notice to the committee.

James Seija, a government professor at St. Lawrence University who has studied the federal judicial nomination process, noted the ABA’s alleged partisan bias has gone both ways. Before the Ronald Reagan administration, Seija said, liberal politicians accused the ABA of being beholden to its membership, which largely consisted of white male corporate lawyers. But the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations ushered in the current era of alleged liberal bias, he said.

A series of not-qualified ratings for Trump appointees has fueled the partisan narrative in recent years, though both Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh were rated as well-qualified for the Supreme Court. Carl Tobias, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law, estimated it’s a ratio of about 100 to 1 or 100 to 2 in terms of nominees that are accurately rated and those that are not.

Even so, Seija said his research into the ratings shows empirical evidence of partisan bias, specifically among Democratic evaluators rating Democratic nominees more highly than Republican nominees. And Tobias said the committee does sometimes make mistakes, such as rating renowned 7th Circuit Judges Frank Easterbrook and Richard Posner as not qualified.

But generally, from Tobias’ perspective, “they’re pretty much on-point and do a nice job on the qualifications.” The Backgrounder does not lay out specifications for the political makeup of the standing committee, but the law professor said committee members are highly respected and accomplished. Sieja said the majority of members are career trial lawyers and have included the likes of Leon Jaworski, the Watergate special prosecutor, and former Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson.

Local reception

Bar evaluations seem to face less controversy at the state level. Trimble recalled working the polls and seeing voters on multiple occasions carry in newspapers containing the results of the IndyBar surveys.

The ISBA hasn’t received much feedback on its evaluation of appellate judges, Henderzahs said, but she takes that as a good sign.

“It’s kind of like when your house is clean — nobody notices it unless something is bad,” she said.

The commitment to impartiality sometimes means tough results for judicial candidates. Trimble, for example, recalled instances when members of the Indianapolis bar gave a judicial candidate an overwhelmingly negative rating.

But Henderzahs sees the flipside when it comes to appellate judges. In 2018, 90% of respondents to the ISBA’s survey voted in favor of Justice Geoffrey Slaughter’s retention.

In Lake County, attorneys submit their survey responses anonymously, Cox said. That kind of safeguard is meant to encourage lawyers to engage with the process of promoting a well-qualified judiciary.

In Indianapolis, Trimble recalled concern among some judges that larger firms could undermine their candidacy. But the other bar leaders say they go great lengths to avoid even the appearance of bias.

“There were long meetings of vetting every single word of what went into the surveys,” Trimble said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.