Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Indiana University Maurer School of Law Dean Christiana Ochoa said those who want to do away with requiring law school admission tests for diversity’s sake have it backward.

The idea that law school diversity would increase if tests like the LSAT and Graduate Record Examination, or GRE, became an optional part of the admissions process is unfounded, Ochoa said.

Instead, she said she’s worried the opposite is true — that the move would actually hurt diversity.

And she is not alone.

Ochoa was one of 60 deans to sign a letter last September pushing back against the proposed change to Standard 503 offered by the Council of the American Bar Association’s Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar.

That proposal would say law schools “may” use a test like the LSAT, not “shall.”

Also signing the letter were Karen Bravo, dean of the IU Robert H. McKinney School of Law, and G. Marcus Cole, dean of Notre Dame Law School.

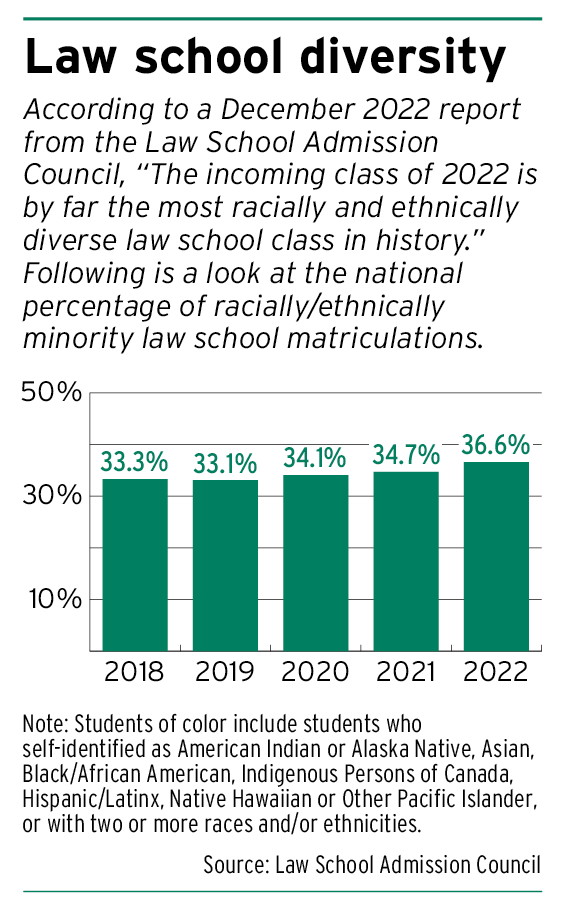

In the letter, the deans said an unintended consequence of removing the testing requirement is that it could “diminish the diversity” of incoming law school classes. They also said standardized tests like the LSAT can be one of many useful data points to assess applicants.

“Even if one is inclined to disagree with our assessment of the likely results of the proposed amendment to Standard 503, it would be premature to adopt the amendment without further study of its likely effects,” the letter states. “For once the LSAT or other standardized test is abandoned as a requirement, the effects will be difficult to reverse.”

Ochoa and other deans appear to be fighting an uphill battle, though.

The council of the legal education section voted almost unanimously in favor of the change in February, even after the ABA House of Delegates rejected it earlier that month.

The resolution is now back with the House of Delegates, which will consider it for a second time at its August meeting in Denver.

Under ABA rules and procedures, the House of Delegates can review a proposed change to the standards twice and concur, reject or make recommendations, but the ultimate decision belongs to the council.

The new standard would not take effect until the 2025-2026 admissions cycle for the class that enters in the fall of 2026.

‘Immediate and radical’ shift

The ABA’s Strategic Review Committee has pushed back on the deans’ assertion that doing away with an admissions test requirement would diminish diversity.

In a November memorandum recommending the proposed changes, the committee said it “does not believe that there is any substantial evidence suggesting that such a deleterious impact will occur.”

The memo pointed out that law schools will still be required to submit information about diversity through the annual interim monitoring process, and if an institution records a “significant decrease” in the diversity of its first-year class, the council could request a written explanation of the school’s admissions policies and practices.

The Law School Admission Council also said in a statement last year that although it shares concerns that a test-optional policy could “undermine diversity efforts,” it believes delaying implementation until the 2026 incoming class would allow more time to prepare and gather data.

Still, deans have said the move feels rushed.

“It is very difficult to sign on to an immediate and radical turn away from the LSAT,” Ochoa said, adding that the move seems “very careless.”

For deans who support keeping an admissions test requirement, part of the argument is that the test helps present a fuller picture of the applicant.

Bravo used the example of a student who doesn’t do particularly well in their undergraduate years or a student who graduates but doesn’t immediately decide on law school, creating a gap in their academic resume. Those students bring a different experience, Bravo said, and a test like the LSAT can offer law schools a more rounded look at that student.

Getting rid of the requirement, she said, would have a “detrimental” impact on those applicants.

Getting rid of the requirement, she said, would have a “detrimental” impact on those applicants.

“By taking away that information, that may create its own problems,” Bravo said. “If we do this more slowly and look at the data, I would have less concern.”

‘Competitive marketplace’

Although the language of the proposed change would leave law schools with the ability to still require an admissions test, Bravo said it’s not that simple.

Higher education is part of a “competitive marketplace,” she said, creating a situation in which IU McKinney and other law schools are competing regionally — even nationally — against schools that drop the requirement.

“If the market leader, whoever they are, then says, ‘Well, we’re going to make it optional,’ the rest of us may be forced to do the same, as well,” she explained.

Some law schools have already said they wouldn’t require an admissions test anymore, according to Ochoa, which she said puts “tremendous pressure” on other law schools, save for maybe the most elite institutions.

Bravo and Ochoa both said their respective law schools haven’t decided if they would keep the requirement if the proposal is adopted.

Notre Dame Law School did not respond to a request for comment.

A ‘burdensome’ layer

Chaka Coleman fits the description of the hypothetical student Bravo and other deans point to.

Coleman got her associate’s degree in 2014, then took a break from school before going back to get her bachelor’s degree in 2018.

Now with five kids, Coleman said she was either pregnant or had kids the whole time.

Coleman said she’s “pretty neutral” on the debate, but she considers the LSAT a “burdensome” additional layer to getting into law school. Accessing the resources that help students prepare for the test requires two things: time and money.

“That’s two things a lot of working people don’t have,” she said.

When it came time for Coleman to take the LSAT, she traveled from Indianapolis to Ball State University in Muncie twice — spots for the test were already full at IUPUI.

Coleman eventually graduated from IU McKinney in 2022 and now works as a contract lobbyist.

She said it’s important for students, especially minorities, to have more access to resources — including time — to study for the LSAT. Some students have family members who have gone through law school, which she said gives them a built-in advantage that many minorities don’t enjoy.

“They’re walking into it blind with zero resources,” she said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.