Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAs the former dean of Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law, Gary Roberts remembers well what happened when he quit participating in U.S. News & World Report’s annual law school rankings: absolutely nothing.

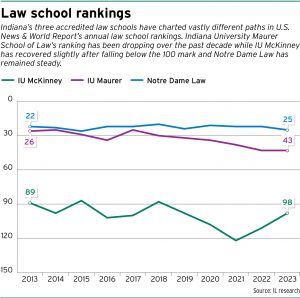

The Indianapolis law school dropped out about 2010 or 2011 but still appeared in the rankings. Although its status plunged from 79th in the 2012 ranking to 89th then 98th in the 2013 and 2014 rankings, respectively, the institution subsequently fell below 100 after it started submitting its data to the magazine again.

“I just thought the rankings were just perverse in every way, shape and form,” Roberts said of his decision to quit. “I guess I was just so offended by them that it just finally pushed me over the edge and I said, ‘To hell with these people.’ I didn’t want to reward them.”

Perhaps the most significant result is that nothing happened outside IU McKinney. U.S. News did not make any changes to its methodology in response, and the rankings, in general, retained their influence over students applying to law schools, professors looking for jobs and law firms hiring associates.

Consequently, whether the current revolt against the rankings will cause some kind of reaction is unknown. Since Yale Law School declared on Nov. 16 it would no longer participate, 11 other law schools have followed, as of Indiana Lawyer deadline.

IU McKinney, Indiana University Maurer School of Law and Notre Dame Law School are still participating. The two IU law schools say they are monitoring the situation and considering their options while Notre Dame declined to share its plans.

Countering the boycott, U.S. News has asserted it will not be making changes and, instead, will continue to rank all fully accredited law schools even if they do not submit their data.

“The U.S. News Best Law Schools rankings are designed for students seeking to make the best decision for their legal education,” Robert Morse of U.S. News said in a statement. “We will continue to pursue our journalistic mission of ensuring that students can rely on the best and most accurate information, using the rankings as one factor in their law school search.”

Ripple effect

Law schools have long complained about the U.S. News rankings. The concerns are echoed in the statements from the deans who have recently joined the boycott.

Namely, they say, the rankings create the wrong incentives for choosing whom to admit and discourage innovation in curriculum and programming. Also, the rankings lead students and employers to the false idea that higher-ranked schools are better than lower-ranked schools.

“That’s just absurd,” Daniel Rodriguez, professor and former dean at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law, said. “… The ordinal ranking just makes it sound like you’re a sucker if you go to a lower ranked school even though they’re essentially the same.”

In a statement about the current cold shoulder being given to the rankings, IU Maurer Dean Christiana Ochoa highlighted the perceived problems with the annual compilation.

“For many years, our law school, together with many others, have implored U.S. News to be more responsive to the critiques and suggestions made to the magazine by law schools subjected to their ranking system,” Ochoa stated. “Our requests have resulted from our observations that the U.S. News Law School Rankings employ a non-transparent and flawed methodology that results in severe and negative distortions in legal education that do not serve students well and are detrimental to society.”

Jeffrey Stake, professor at IU Maurer, said he was intrigued when U.S. News first published its rankings about 35 years ago and has been studying their effect since.

Applicants, Stake said, are so influenced by the rankings that they will turn down scholarships from schools better suited to their interests to attend a higher-ranked school even though they may have to pay $50,000 to $100,000 more. Likewise, law firms look at the rankings when interviewing candidates for jobs, and alumni become agitated when their alma mater falls in the rankings because they believe the value of their J.D. is reduced.

But even as law schools denounce the rankings, they have also altered their admissions strategies to better position themselves in U.S. News.

Stake explained the magazine has emphasized LSAT scores and undergraduate grade point averages in its calculations, so law schools are courting and offering scholarships to students with the highest scores and grades who often do not need the financial assistance. The applicants who earned a bachelor’s degree in a more demanding subject but have a lower GPA as a result, or who could most benefit from a scholarship, are being bypassed.

“It’s really a travesty,” Stake said. “… You’re turning down students that look like great applicants for law school and then for the legal profession and good for the public once they’re in the legal profession and you’re saying, ‘No, let’s go with this other person that doesn’t hurt us in the U.S. News.’”

Confluence of events

Karen Bravo, dean of IU McKinney, said she is surprised at the revolt but noted most of the institutions joining are in the top tier, or what are called the T-14 law schools. Yale, Harvard, Stanford and the others have the resources and self-perpetuating reputations to withstand any repercussion caused by ignoring U.S. News.

“It’s a question of power,” Bravo said. “The schools that are in the T-14, they’re able to make this move and they’re able to say, ‘No,’ to make these points that I think many of us in the legal academy make. I do not know at this point whether or not this is going to be a transitional moment.”

Law schools are dropping the rankings just as the U.S. Supreme Court appears poised to find race-based admissions unlawful. The Wall Street Journal editorial board and others have speculated that Yale and Harvard are leaving the rankings so they can continue to enroll more diversified classes, which might have lower LSAT and GPA numbers, without harming their U.S. News status.

In addition, the American Bar Association is ending the requirement that law schools use a valid and reliable admissions test like the LSAT or the Graduate Review Exam.

Rodriguez said he sees the exit of the law schools along with the potential for changes in affirmative action and entrance exams as possibly diminishing the credibility of the U.S. News rankings. That, he said, could bring a transitional moment, as law schools could then begin experimenting with admissions and curriculum.

What will most drive law schools to innovate, he said, is pressure from public officials as well as law firms and businesses that hire the J.D. graduates. When external entities insist upon innovation, some schools will take bold steps.

“If there’s going to be a big change, it’s going to come from folks just demanding a really different kind of innovation in legal services and legal education,” Rodriguez said. “… I’m moderately hopeful that’ll happen and that’s why I’m generally supportive of the U.S. News revolution.

“… I don’t think it’s a big, gigantic revolution in legal education,” he added. “That will require many other steps for that to happen.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.