Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowFrom 2017 through 2019, nine legislators exited the Statehouse before their terms expired, requiring the state’s caucus system to ramp up to handle the large number of vacancies and bringing renewed attention to political party processes that choose who will represent voters.

Precinct committee members in districts around the state were called upon to pick replacements for General Assembly leaders such as former Senate President Pro Tem David Long and Luke Kenley, chair of the Senate Committee on Appropriations, as well as for relative newcomers such as Mike Braun, who resigned nearly three years into his term in the Indiana House to run for the U.S. Senate.

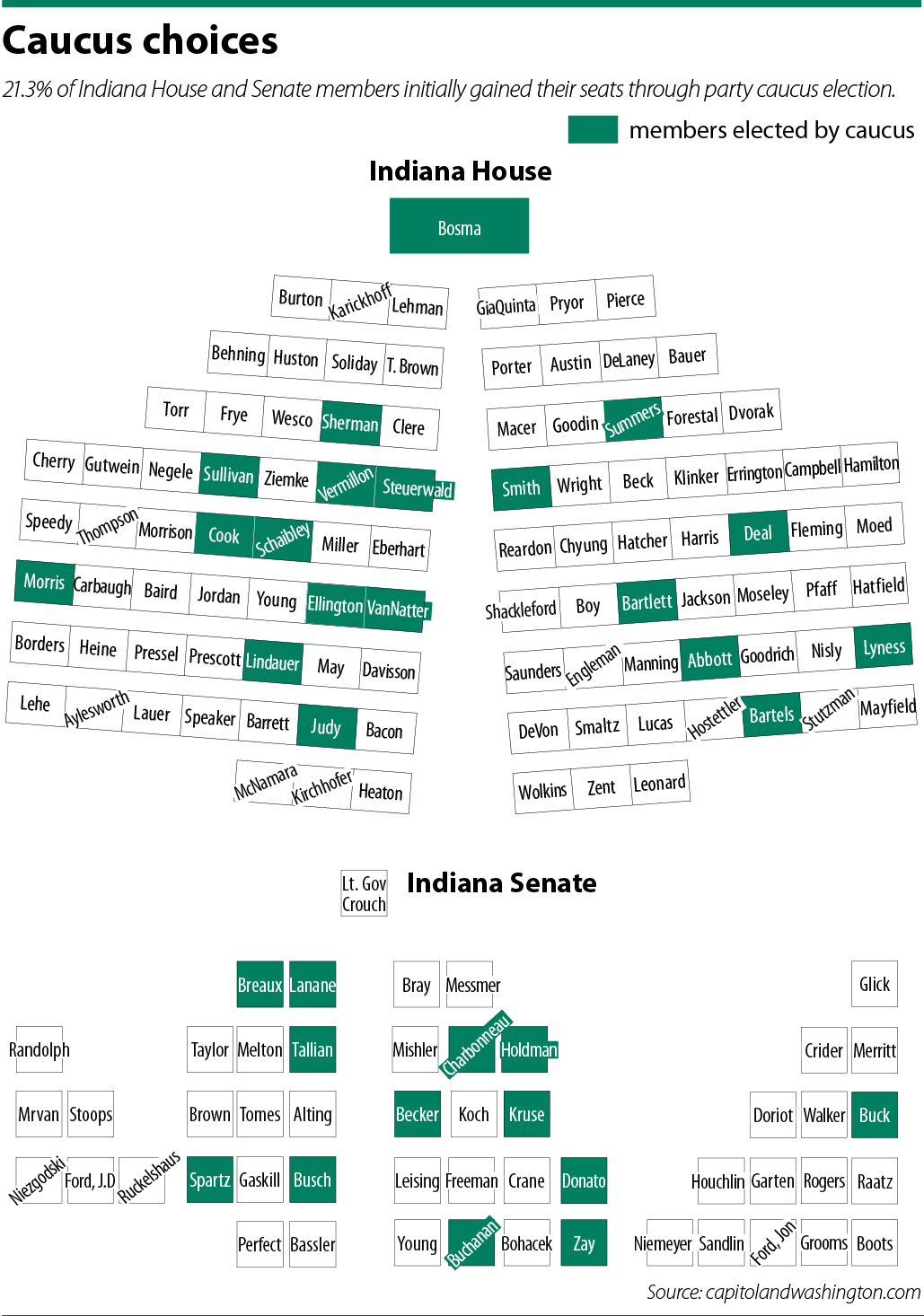

At present, 21.3% of Indiana legislators first entered the Statehouse through a caucus election, according to data compiled by Trevor Foughty and posted on his Capital & Washington website. Foughty pointed out that officials caucused in eventually have to run in a general election if they want to retain their seats, as 26 of the current 32 caucused members have had to do.

Foughty was noncommittal as to whether the caucus is a valid way to select legislators. However, he noted the caucus system ensures voters will continue to be represented in the Statehouse even when their legislator resigns, dies in office or accepts a gubernatorial appointment. Also, an election via caucus is much less of a burden on taxpayers than a special election would be.

Within the Republican Party, the caucus system has brought more women into the ranks. Three of the most recent caucused members were female, bolstering the number of Republican women in the House to 11 and in the Senate to eight. Foughty said the increase is not a coincidence because women are being recruited to run and more are seeking public office.

Rep. Dollyne Sherman, R-Indianapolis, had been asked to consider running in 2020, but the timetable got advanced when her district’s representative, David Frizzell, resigned from the House in April 2019. Family obligations weighed heavy with Sherman’s husband in the final phase of recovering from an illness and her son finishing his college education, but she said after a lot of prayer, she decided to toss her hat into the caucus ring.

Running in the caucus, Sherman said, was not necessarily any easier than a general election. She had just 30 days to introduce herself to precinct committee members, where she emphasized her previous experience – including working for governors Robert Orr and Mitch Daniels – then meet with them individually to discuss issues such as the expansion of Interstate 69.

As for whether the caucus system levels the playing field for women, Sherman was unsure, though she noted she beat five men in her caucus election. She could see female candidates being in a better position than in a general election because the key to the entire process is to make connections.

“What I was told when I sought out advice for running in the caucus was that relationships matter,” Sherman said. “I only knew four of the 40 (precinct) people personally, so I had to rely on relationships with others who knew me and could vouch for me.”

‘Party faithful’

Indiana’s caucus election process was developed in the early 1970s when the Legislature switched from meeting for two months every other year to gaveling in for a session every year, Foughty said. Prior to the annual sessions, having a vacancy was not as much of a concern because the seat would likely be filled by the time the General Assembly began its work again.

Asked if the caucus system works, Andrew Downs, director of the Mike Downs Center for Indiana Politics at Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne, gave the simple answer of yes.

Then he continued, “Vacancies are getting filled, so the caucus system does work.”

On the positive side, caucusing allows candidates who might not be viable otherwise to be competitive, Downs said. The caucus campaign, although shorter, enables the candidates to meet and talk directly to the precinct members, while meeting with all the voters in a general election is impossible.

The downside is that the precinct members tend to be more rigorous in political ideology than the average voter, Downs said. They could be attracted to the caucus candidate who matches their views, which probably would be more extreme than those of the average voter in the district.

The downside is that the precinct members tend to be more rigorous in political ideology than the average voter, Downs said. They could be attracted to the caucus candidate who matches their views, which probably would be more extreme than those of the average voter in the district.

Sen. Dennis Kruse, having long dreamed of being a state legislator, twice ran for the Indiana Senate in 1974 and again in 1978. He lost narrowly but was later convinced to vie for the House seat that opened when Rep. Orville Moody died in 1989. Fifteen years later, he moved into the Senate through another caucus election following the death of Sen. Bud Meeks in 2004.

“I think it is the most practical way of handling replacing a person in office,” Kruse said of the caucus system. He added that the caucus is comprised of the “party faithful who are as good a people anyone can get to find a replacement within the party.”

Certainly the party’s precinct members picked him initially, but in every general election he has run in since, Kruse has garnered a majority of the voters’ support. Readily recalling each opponent and final vote tally, the Auburn Republican credited his success with reflecting his constituents’ views when he votes on bills in the Statehouse.

Musing on alternatives to the caucus system, Kruse said a possibility would be to have the governor appoint someone or have the legislators themselves vote on a replacement. But he quickly dismissed those methods, saying he still prefers a caucus election because it gives the choice to the people who live in the district.

Not a full-time job

Legislators have left mid-term for health concerns, family demands, new jobs or personal reasons. Downs acknowledged voters do get aggravated when someone who committed to represent them for the full term takes an early exit, but he questioned whether voters would want to force someone to serve in the Statehouse who did not want to be there.

Elected officials, Downs said, need a way out, especially if the office is not a full-time job.

Former Rep. Joe Taylor, D-South Bend, resigned shortly after winning a second term in 2018. He told the South Bend Tribune that the United Auto Workers had approached him about a job two months before the November election, but he did not withdraw from the race because he did not want his party to lose the seat.

“As a lifelong Democrat, I think my job first and foremost was to keep the seat in the party’s hands,” Taylor told the newspaper.

Current St. Joseph County Democratic Party chair Stan Wruble was surprised and found it “a bit concerning” that one in five General Assembly members were chosen by caucus. Yet, like Downs, he noted the Legislature is part-time and said the caucus system is the best available for selecting replacements.

“I think ideally the individual who is selected should be chosen by the people,” Wruble, an attorney with the Wruble Law Group, said. “A caucus is necessary when the legislator can’t fulfill the term, but I think for the majority of the time, it should be the will of the voters.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.